Altared Spaces:

New Orleans Revisited

Anna M. Chupa

Director, Design Arts Program and

Associate Professor, Department of Art and Architecture

Lehigh University, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, USA

anna.chupa@lehigh.edu

Michael A. Chupa

Senior Computing Consultant, Environmental Initiative

and Library and Technology Services

Lehigh University, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, USA

mike.chupa@lehigh.edu

Abstract

The imagery in Altared

Spaces is based upon transformations of two traditions: African Vodun in

New Orleans, specifically Priestess Miriam’s New Orleans Voodoo Spiritual

Temple, and the Italian-American celebration of St. Joseph’s feast day. The

latter, which centers on providing food to the poor, is especially poignant

given New Orleans’ devastation following Hurricane Katrina.

The audio portion of the

installation is a continuously evolving real-time performance derived from

traditional drumming sequences, both as a celebration of the spiritual and

artistic expression of those brought to New Orleans against their will during

the African diaspora, and as a prayer for the current diaspora of New

Orleanians who do not have the means to come home. The computer-moderated image

sequences are coupled to the audio generation in a feedback loop that provides

serendipitous opportunities for each display modality to influence the temporal

evolution of the other. The agglomeration of imagery on the computer display

echoes the process of assembling an altar.

1. Background

Our video imagery is drawn

from still photography and video sources gathered from collaborations beginning

in 1996 for an ACM SIGGRAPH exhibit [1], through several research trips in the

intervening decade, and culminating in a research trip in March 2006 for the

first St. Joseph’s feast day observance following hurricanes Katrina and Rita.

1.1 Saint Joseph’s Day Altars

St. Joseph is the patron saint of

workers, of families, and the poor. The tradition of building an altar to St.

Joseph began in gratitude for St. Joseph’s intercession during a famine in

Sicily. In New Orleans and several other American cities, the tradition grew

into more public events celebrated in churches, parish halls and cultural

centers. Local newspapers published home altar locations open to the public.

During March, 2006, we visited the

Lower 9th Ward, Violet, and Arabi. There, dark streets with no

electricity demonstrated that recovery efforts were still stalled. Several

church parishioners were gathered in a dome tent with a “new kind of disaster

relief organization,” Emergency Communities. This group of volunteers,

“frustrated with the slow mobilization that plagued many traditional relief

organizations,” had poured into the Gulf Coast region, “slept in tents, ate

what they could, and slowly energized broken towns and desperate people. In the

first few months after the disaster, such independent relief efforts were often

relied upon when action, not bureaucracy, was needed.” [2]

1.2 Vodun Altars

Christian generosity and the concept

of Yoruba Ashe that underlies the

voodoo practice of feeding the spirits share many essential elements. Ashe is

the sacred power to make things happen. As Robert Farris Thompson writes, Ashe

can be diminished by selfish living: “This

means that one must cultivate the art of recognizing significant

communications, knowing what is truth and what is falsehood, or else the

lessons of the crossroads—the point where doors open or close, where persons

have to make decisions that may forever after affect their lives–will be lost.”

[3] Beneath the sacred canopy of a rich religious tradition, individuals emerge

from crisis “aware of the new possibilities of existence.” [4]

“The goal of all Vodou, [Santería and Candomblé]

ritualizing is to…heat things up so that people and situations shift and move,

and healing transformations can occur. Heating things up brings down the

barriers, clears the impediments in the path, and allows life to move as it

should.” [5]

Voodoo in Priestess Miriam’s

practice combines aspects of Santeria (Cuba, Miami, New York), Vodou (Haiti),

Spiritualism (Chicago, New Orleans) and Catholicism. As Ishmael Reed

characterized New Orleans Voodoo, it is a spiritual and artistic gumbo that

“Jes Grew.” [6] In honor of that spirit, what grows generatively from the

collected experiences of ten years—private altars and public ceremony,

grassroots relief efforts, the ever-present Mardi Gras beads and the voodoo

shops—is the authentic germ that “jes grew.” This is our attempt to give

something back, and at the same time it is a cry for action.

2. Installation Details

The

installation integrates audio and video presentations within an altar framework

drawn from the Vodun and St. Joseph’s altar traditions. This syncretic

portrayal of New Orleans’ cultural traditions is intended both as an homage to

each distinct tradition, and as a plea for the preservation of the city’s

identity, which has allowed these traditions to develop in close proximity.

2.1 Hardware Architecture

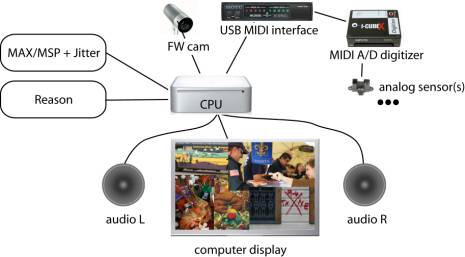

The hardware

architecture for the Altared Spaces installation is shown in Figure 1. External

inputs include a Firewire video camera, analog sensors which are passed to an

A/D digitizer, Infusion Systems’ i-CubeX, producing MIDI output; these signals

are passed to the CPU via a MIDI interface (MOTU micro lite). At the CPU, the

various inputs are processed by a series of Max/MSP and Jitter (cycling74.com)

patches to produce a visualization stream and an audio output stream via the

Reason (propellerheads.se) software synthesis module. The input video signal

can be used in two modalities: as a viewer proximity detector or as an image

source.

2.2 Software and Dataflow Architecture

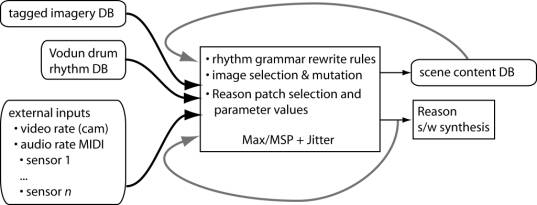

Two databases

are added to the software architecture in Figure 2: a tagged imagery database

developed from photographic source material, and a rhythm database containing a

structured grammar description of several drumming themes associated with Vodun

loa. This grammatical description is used by an L-system [7, 8] patch to

provide a recursive audio stream of indefinite length. The processing pipeline

terminates with the scene content database mapped to the computer display, and

the software synthesis module routed to the CPU audio output.

The central

Max/MSP+Jitter processing patches provide database access and external stimuli,

and produce realtime outputs to populate the scene database and a MIDI output

stream controlling a software synthesis module. In building this installation, we have

eschewed direct perceptual audio mappings (e.g.,

pitch), but have rather provided cognitive mappings more commonly associated

with the experience of music. [9, 10] Stochastic sampling of the

external stimuli provides an aleatory character, and two feedback mechanisms

(from the scene content database and the output MIDI stream) are likewise fed

back into the Max system to provide additional inputs that are associated by

the viewer/listener with the current display contents. Tags associated with

currently displayed images are ingested in this feedback stage. Synaesthetic

feedback is also supported so that visual scene content changes can trigger

audio events, and vice versa.

Figure 1: Altared

Spaces hardware architecture

Figure 2: Altared Spaces software architecture

References

[1] Chupa, Anna. “Altar” in The Bridge: SIGGRAPH 96 Art Show. Contemporary Art Center and

Contemporary Arts Center and the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center in New

Orleans, LA. 23rd International Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive

Techniques. August 4-9, 1996.

[2] Mulroy, James. 2006. “Emergency Communities: About

Us” online: emergencycommunities.org

[3] Thompson, Robert Farris. Flash of

the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy. New York: Vintage

Books. 1984. p. 19.

[4] Thompson, Robert

Farris. Face of the Gods: Art and Altars

of Africa and the African Americas. New York: The Museum of African Art.

1993. p. 305.

[5] Brown, Karen. Mama Lola.: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn. Berkeley:

University of California Press. 1991. pp. 134-135.

[6] Reed, Ishmael. Mumbo

Jumbo. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1972.

[7] Prusinkiewicz, P and

Lindenmayer, A. The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants. Springer, 1991.

[8] Song, H. J. and Beilharz,

K. "Time-based Sonification for Information Representation", in World Multi-Conference on Systemics,

Cybernetics and Informatics, Orlando, USA, July 10-13, 2005.

[9] P.

Vickers, ''Ars Informatica - Ars Electronica: Improving Sonification

Aesthetics,'' in Understanding and

Designing for Aesthetic Experience Workshop at HCI 2005. The 19th British

HCI Group Annual Conference (L. Ciolfi,

M. Cooke, O. Bertelsen, and L. Bannon, eds.), Edinburgh, Scotland, 2005.

[10] P. Vickers and B. Hogg, ''Sonification Abstraite/Sonification

Concrète: An `Æsthetic Perspective Space' for Classifying Auditory Displays in

the Ars Musica Domain,'' in ICAD 2006 -

The 12th Meeting of the International Conference on Auditory Display (A. D.

N. Edwards and T. Stockman, eds.), London, UK, June 20-23, 2006.