A Socializing

Interactive Installation in the Urban Space

Carolina Briones, MSc

Bartlett School of

Graduate Studies, University College London, UK

Ava Fatah gen. Schieck, MSc

Bartlett School of Graduate Studies,

University College London, U.K.

Ava.fatah@ucl.ac.uk

Chiron Mottram, MSc

Bartlett School of Graduate Studies,

University College London, U.K.

Abstract

In this paper we present the LED-s Urban Carpet: an interactive urban

installation using a body-input as a form of a non-traditional user interface.

The installation was tested in the city of Bath, UK. The aim is to generate a novel urban experience, which can be introduced in different

locations in the city and with different social situations.

The

installation represents a game with a grid of LEDs that can be embedded as an

interactive carpet into the urban context. A pattern of lights is generated

dynamically that change in real time according to pedestrians movement over the

carpet. In this case the pedestrians become active participants that influence

the generative process and make the pattern of LED-s change depending on the

location of one or more participants.

The paper suggests that introducing this kind of display in a social

scenario can enrich the casual interaction of people nearby and this might

enhance social awareness and engagement. However, we should point out that a

number of factors need to be taken into consideration when designing the

interactive installation, especially when situated within the urban space.

We believe that

developing the LED-s Urban Carpet and evaluating it as part of the public urban

space is a powerful way to help us understand the whole cycle of designing with

the new medium. The experience we present here can assist designers in

understanding difficulties and issues that need to be taken into account during

the design of an interactive urban project of this nature.

1.

Introduction

Traditionally, architecture has been perceived as the static

floors, walls and roofs that surround us. With the dawning age of ubiquitous

computing technology

is slowly disappearing into the surroundings, becoming unobtrusive and

ubiquitous [1]. Physical computing and digital

systems are becoming more pervasive in our

architectural and urban spaces, allowing us to perceive architecture as

a dynamic and adaptive surface that can respond to the surrounding environment. This brings the challenge of

developing novel computing interfaces that move beyond the Graphical User

Interface (GUI) and the usage of desktops and laptops and can be embedded into

existing or new architectural and physical environments.

1.1 Urban Environment as a platform for social interaction

2.

Related Projects

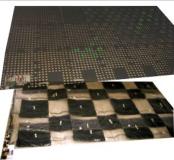

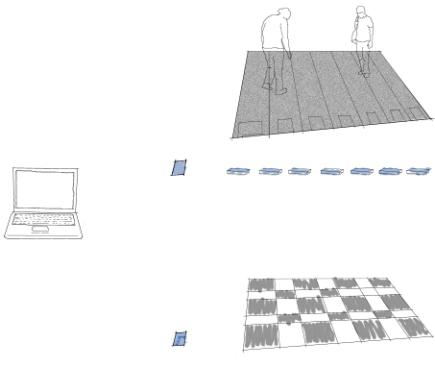

3. The LED-s Urban Carpet

Prototype

Down: Pressure Pads

The

project is conceived as a portable urban installation in the form of a carpet

of LED-s. The LED-s Urban Carpet

consists of two layers (fig. 1). The first is a grid of light-emitting diodes

(LED-s), which interact with pedestrians by tracking their paths over the grid.

The lights will turn on or off depending on a

computer program, which defines the behavior of each light at every instant.

The

project is conceived as a portable urban installation in the form of a carpet

of LED-s. The LED-s Urban Carpet

consists of two layers (fig. 1). The first is a grid of light-emitting diodes

(LED-s), which interact with pedestrians by tracking their paths over the grid.

The lights will turn on or off depending on a

computer program, which defines the behavior of each light at every instant.

The program is written in

Processing language using a Boid algorithm based on Craig Reynolds’ rules [10]

to simulate a flock of seagulls that follow the pedestrian. It gives the whole

experience a recreational and fun atmosphere. The location of each pedestrian

over the carpet is recognized by the second layer, a grid of pressure pad

sensors, which is located behind the grid

of LEDs. Both the LED and pressure pad layers form a unit that sends the

user’s input to the computational program and performs the outputs as well (in

the form of seagulls) (fig. 2).

3. Testing Process and Initial

Findings

In order to investigate the social

and practical issues in the public architectural space raised by implementing

the interactive installation, the prototype was tested during different

sessions in the heritage city of Bath and as follows: A) different locations

were selected. These varied in the movement flow during the day, land use and

the specific role of each location in relation to the city centre area; B) a

range of empirical observation methods and a questionnaire were implemented; C)

the public interactions with the prototype were observed and annotated. During

the interaction sessions the following common emergent patterns were observed:

- Curiosity: while assembling the

prototype, passers-by gathered around the area to see what was going on,

some asked for information about the prototype.

![]()

esting Process and Initial

Findingssocial interaction

2.

Awareness of the experience: In

some cases it was built up amid anticipation as people used relevant prior

experience and expectations of a new experience (e.g., frequently the public

characterized the prototype as a “dance carpet” before they interacted with

it). Different levels of awareness were noticed among people walking around the

area, from glancing at the interactive prototype but then continuing their way,

to people stopping around the prototype and asking about it, trying to

understand how it works (peripheral awareness, focal awareness to direct interaction).

![]()

During the interaction sessions we

noticed that there is a direct relation between the way in which people

gathered around the prototype, and the level and type of interaction with it

and between people nearby. When strangers interact with the prototype, unlike

the case with friends, they tend define their territory and stay on one side

and not cross the area of the other user, leaving a kind of mutual acceptance

distance between users (fig. 7).

![]()

Finally, the test sessions have

shown that the movement flow of passers-by and activities happening near the

locations has a direct impact in the interactive installation final

performance; when the display was located in an area with a higher rate of

pedestrian traffic it was more difficult to catch people’s attention than in

locations where the speed flow tended to decrease due to the spatial

characteristics of the physical environment and people activity (e.g.: window

shopping).

4. Conclusion

Our investigation suggests that the

success or failure of a large interactive display depends on internal

properties of the display and external factors of the social and physical

surroundings. The central problem in

setting up new forms of technological surfaces in public space is people’s

uncertainty regarding how to interact with the display. One factor, which needs

to be taken into consideration, is the physical affordance of the interactive

display, which engenders certain kinds of social interactions. In this case,

installing a large interactive display as a horizontal surface in a public

space encourages people to walk over and congregate around it in a socially

cohesive and conducive way. People congregate around it or over it, in a

non-hierarchical manner, where each user has the same possibilities for

controlling the interaction performance.

In addition, it was possible to

observe that social proximity or person-to-person distance was necessary

between the public interacting at the same time within the display. Distance,

which was different between strangers compared to that between friends. In this

regard, the LED Urban Carpet illustrates a weak point: Its size is not big

enough to host the interaction between many people at the same time. During the

test sessions, the most common pattern observed when strangers were interacting

with the carpet was that they waiting for their turn.

However, not only the physical

properties of a display can have quite profound effects on the way it is used

in a public setting, the affordance will also vary depending of the nature of

the space where it is located (e.g., a park, street, bus stop, etc.). Each

space has different attributes as do the people who are interacting with it

[11]. Accordingly, it is possible to argue that different kinds of surfaces

will be needed to augment, support and enhance what people already do in that

specific space [12] and it seems that the ability of an interactive large urban

display to enhance social interaction depends on the social atmosphere where it

is located, the type of audience and cultural background, the affordance of the

prototype, and the affordance of the environment where is located.

Hence, large interactive

public-displays have the potential to generate social interaction and awareness

around them. However, in situating them in different locations and social

environments, diverse behaviours and reactions will emerge from the public,

which the designer could not necessarily predict.

5. Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express

their gratitude to Alasdair Turner and Chris Leung for their contribution. This

project was conducted as part of the MSc AAC at UCL and is partially funded by

Cityware (EPSRC: EP/C547691/1).

6. References

[1] Greenfield,

A. Everyware: The Dawning Age of

Ubiquitous Computing, Peach

pit Press (2006).

[3] Streitz, N.

A., Rocker, C., Prante, Th., Stenzel, R., & Van Alphen, D., Situated

Interaction with Ambient Information: Facilitating Awareness and Communication

in Ubiquitous Work Environments. In Proc.

HCI International 2003, (2003).

[8] Equator: http://www.equator.ac.uk/

[9] Lozano-Hemmer, R..: http://www.lozano-hemmer.com

[10] Reynolds, C.: www.red3d.com/cwr/boids/applet/.

[12] Briones, C. LED-s Urban Carpet:

A portable Interactive Installation for Urban Environments. MSc thesis, UCL, London (2006). (unpublished)