Aesthetic

Perception in Design

(Developing a Product Language)

Dr

Hengfeng Zuo, PhD, MSc, MA, BSc

Research Fellow in Product Design

Faculty of Technology, Southampton Solent

University, UK

Email: heng-feng.zuo@solent.ac.uk

Mark Jones, BA, MCSD

Principal Lecturer in Product Design

Faculty

of Technology, Southampton Solent University, UK

Email: mark.jones@solent.ac.uk

Mr Qiu

Song, MA, BA

Academy of Art & Design, Tsinghua University,

China

qiusongtty@hotmail.com

Dr Liu Xin, PhD, BA

Academy of Art

& Design, Tsinghua University, China

Email: greenth@sohu.com

Abstract

Ugly things are

hard to sell. Aesthetic designs are often perceived as easier to use. This project has been set up to explore

the extent to which young designers are able to manipulate form, styling and

create an overall perception of a positive aesthetic. At the same time, we aim

to explore the DNA of a product¡¯s aesthetics and develop a linguistic system ¨C

product language. This system will differ from the traditional ¡®Semiotics¡¯ or

¡®Semantics¡¯, and although it will include these aspects, it will probe deeper

into the elements of formal aesthetics such as the shape, colour, material,

texture, proportion, dimensions, space, etc. This language system will be a

combination of both formal/external presentation and the

representative/embedded meanings of a physical product. It will enable more

effective communication between the various people involved in the product

development processes and in particular, the relationship between designer and

consumer. We have run a series of practice-based design workshops for

undergraduate design students both in the UK and China. This paper will

showcase the stage results from this workshop.

1.

Aesthetic

experience and association

What makes

a product aesthetically appealing? This is an

old topic but always triggers new debates in the design field. Aesthetics, usually defined as the branch of philosophy that deals with

questions of beauty and artistic taste [1], has been recognised since antiquity

and has continually evolved over time. The word beauty is commonly applied to things

that are pleasing to the senses, imagination and/or understanding. It is often

what an artist or a designer endeavours to achieve in their works, either for

personal or mass interest and pleasure.

Aesthetics might have

different connotations if envisaged from different perspectives, such as

functional aesthetics, technological aesthetics, formal aesthetics,

psychological and cultural aesthetics etc [2], in addition to the sensory

aesthetics, which is the fundamental element of aesthetics. Though, an

aesthetic design may not have all these connotations at the same time. However,

it is widely agreed by scholars that sensory perception plays an intrinsic role

in aesthetic experience [3, 4, 5]. In other words, aesthetic experience starts

from pleasing the senses in the first instance. It has even been argued that

aesthetic experience is restricted to the (dis)pleasure that results from

sensory perception [5]. Actually, we can perhaps say that every experience

starts from our senses, as our sensory organs serve as the windows through

which human beings are able to know and feel the external world, but not all

experiences can be attributed to aesthetic experience. This implies that

sensation is not the only element of aesthetics. Although it might represent the

dominant one it does not represent the whole aesthetic experience. It is the

door through which we enter into the experience of beauty; Individual isolated

stimuli, either a colour, a sound, or a smell, can elicit physiological

response (e.g., comfort or excitement) such as represented by the change of

pulse, blood pressure. However, this cannot equal aesthetic response unless it

evokes our emotions.

You might say that you

find a particular curve, line or a colour to be beautiful, even when separated

from any context. However, there will be something underlying your instinctive

response to these stimuli that will share an association with an image or

meaning you will have stored in your memory, no matter how vague the

recollection. For example, the colour of green might remind you of freshness,

purity, hope, or the curvaceous lines resemble organic lives or the form of a

beautiful etc. This can be termed as ¡®association¡¯.

Association

plays a part in the process of aesthetic experience, and is connected with the

formal aspect of an artwork or designed product. Fundamental forms are given meaning through association with previous

knowledge of the world stored in long-term memory [6]. With

certain associations, meanings and emotions added to the primary sensory

experience, could the overall aesthetic experience be enriched to a greater

extent?

Exploring the aesthetic

association with designed products is one of the purposes of this research.

2. Product

language

No matter what kind of

aesthetic experience takes place in our mind, through the sensory interface

with any designed product, we often need to express this experience and

communicate our thoughts with others (designers, engineers, consumers, etc), in order to understand and generate good product aesthetics

and perception. This ¡®expression of

information¡¯ can be used as reference point when developing any new product.

For such expression and communication, we need a tool/dialogue through which we

can work ¨C product language.

In

our understanding, product language can speak about product¡¯s functions, forms,

style, aesthetics, value, culture, personality, etc. Product language was ever

said to have two main constituents: the formal and

the semiotic [7, 8]. The term ¡®semiotics¡¯ derives from the linguistics, deals

with the study of signs [7]. Another similar term also deriving from

linguistics is semantics, which deals with the study of meanings [8, 9].

Product semiotics and product semantics, literally, deals with the signs and

meanings of the product. However, this tends to focus more on the symbolic and

representative aspect. Product semiotics and

semantics might not always speak of aesthetics [9, P151], although there is a connection. For example, they share

some commonality when addressing the symbolic /representative meanings or

associations of the product. The adoption of the term product language

is based on the purpose of covering a wider range of information that a product

can deliver per se. Not just the symbolic and representative meanings, but also

firstly its formal aesthetic features via the sensory routes and thereafter the

connection between the formal aesthetic features and the

symbolic/representative meanings. However, there is little evidence to suggest

that in-depth research in the field of formal aesthetics has been conducted,

despite design researchers having taken a large interest in the product

language¡¯s semiotic aspects. There is the potential for combining product

semiotics and formal aesthetic features in order to establish a more complete

product language system [8].

In this research, our

second aim is to explore the ¡®product language¡¯. Initial research was conducted

to see if there is any common vocabulary used by people to describe a product¡¯s

aesthetics. Also of importance are the associations the product would carry,

and the possible correlation between the formal elements and the associations.

This could helpfully contribute to establish a sort of formal DNA for a product

or group of products. This may serve as the reference point for the design and

development of any new member to that family of products.

3. Preliminary

study of aesthetic description

The method for a pilot

study was asking people to give their verbal description of product aesthetics.

At this stage, we are not going to distinguish which descriptors can be

attributed to the aspect of formal aesthetics or the semiotic aspect of a

product. We will try to look at this division and a possible correlation

between these two aspects in a later stage. We used 10 top products that had

already been selected by an international panel of judges, representing those

products that were worthy of an international design award and having strongly

aesthetic appeal - Hannover, 2005 International Forum (IF) Design awards (see

Figure 1). These products represented different product areas such as medical,

domestic, technological, industrial etc and were selected as the products that

would be used for product description. 113 completed questionnaires were

collected from design students at Southampton Solent University. We presented

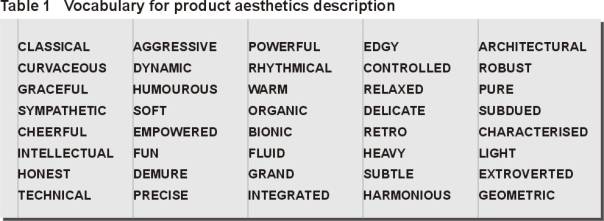

students with a list of pre-selected vocabulary for their reference (see Table

1). However, participants were also encouraged to use their own descriptive

words.

From the results we

found two phenomena. One, different products may share similar aesthetic

properties. Secondly, these described aesthetic properties cover both formal

aspect and symbolic aspect or associations, and the formal aesthetic

descriptions are correlated to some extent with the associations.

Usually, it seems

difficult to find aesthetic properties to fit all design artefacts, and there

is no sense in trying to apply the aesthetic features of one product to another

[9, P.151]. Nevertheless, this does not mean that different products should not

have some commonality in the expression of aesthetic properties. It is this

very commonality or similarity in aesthetic features, even if this commonality

can be quite limited, that can be applied as a reference when considering the

design and aesthetic of a new product. The widely used mood-board is a good

example of this.

Figure

1 Top 10 designs presented to design students for aesthetic evaluation

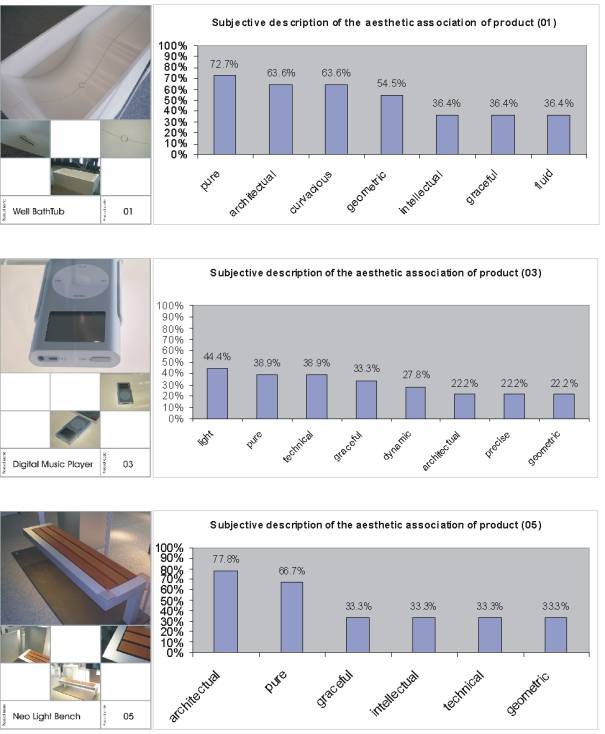

Figure

2 the aesthetic description of three different products

Figure 2, as an

example, shows that the aesthetic descriptors ¡®pure¡¯, ¡®architectural¡¯, and

¡®geometrical¡¯ are shared by three different products (a bathtub, a MP3, and a

bench). For a direct and simple understanding, we may regard the descriptor

¡®geometrical¡¯ as the description of shape, which is an element of formal

aesthetics; whist ¡®architectural¡¯ seems to be the description of an association

or metaphor, which has more sense of semiotic property. The descriptor ¡®pure¡¯

can be perceived as a visual simplicity (with the opposite as ¡®noisy¡¯ or

¡®complicated¡¯). It is hard to say that the description of ¡®pure¡¯ is completely

a formal aesthetic feature because when we say something is pure, that includes

your emotional feeling of appreciation. In other words, verbal description

cannot always make a clear division between the formal aesthetics and semiotic

meaning. A further statistical analysis revealed that these three descriptors

are correlated to a certain extent (with the correlation efficient r³0.5) under this research context.

Another example of such

a correlation has been shown between the descriptors of ¡®harmonious¡¯,

¡®delicate¡¯, ¡®organic¡¯, and ¡®curvaceous¡¯. Again, here ¡®curvaceous¡¯ may

completely address the formal aspect ¨C shape; whilst ¡®organic¡¯ integrates an

association between the product form and the life forms found in nature,

whether the human body, types of animals, or a drop of water, usually can be

¡®delicate¡¯ and ¡®curvaceous¡¯. Accordingly, it is easy to understand that these

natural forms are correlated with ¡®harmonious¡¯ as they reflect the results of

natural evolution.

It is worth conducting

further research to explore these aesthetic descriptors and their correlations

in a deeper level. And to see, when product context changes, how these descriptors

and correlations change as well. As we have seen, although some products used

in this research share some commonality of aesthetic properties, this cannot be

taken as a universal principle. It is argued that specific product language and

their correlation might be different from, say electronic products, furniture,

and transport tools etc.

4. Student

Design Workshop and Evaluation

The third aim of this

research is to explore to what extent young designers are able to manipulate

form and aesthetics. This has been conducted by running a practice-based design

workshop, where students completed a series of exercises plus a six-week design

project (MP3 & Speaker Unit). The MP3 project and some of the exercises are

attributed to a top-down process, where targeted

aesthetic perception comes first and is then translated into the 3D forms

designed by students. Other exercises are attributed to a bottom-up process, where the students are

shown images of products (4 product categories and 50 images of different styled

products for each category), and asked to interpret the aesthetic features into

and make a judgement as to the product perception. The Workshop has been

conducted at Southampton Solent University (UK) and Tsinghua University (China)

respectively. Further analysis of the results will help reveal the extent to

which cultural influence may impact on the design aesthetic and the level to

which product language can be used cross culturally.

In this paper, we

present the completed MP3 & Speaker design project and the evaluation of

their aesthetic and associative features. The design brief for MP3 was based on

three groups of descriptive words regarding a product aesthetic. We used the

correlated descriptors found in the pilot study to constitute the groups.

However, we further modified the combination of the descriptive words as

follows.

Group 1: Pure, Architectural,

Geometrical, and Technical

Group 2: Curvaceous, Organic, and

Fun

Group 3: Graceful, Cheerful, and

Powerful

Within group 1, we give

an extra descriptor of ¡®technical¡¯. Within group 2, ¡®curvaceous¡¯ and ¡®organic¡¯

remain, but added with an extra descriptor ¡®fun¡¯. Within group 3, the three

descriptors, from the pilot study, do not show any correlation between each

other. Students are then asked to produce designs for the MP3 & Speaker

Unit in line with any of the three groups of aesthetic properties. These

deliberate arrangements of design brief aim to give more challenges for young

designers to manipulate and balance the formal elements (mainly form, colour

and surface finish), to match a particular aesthetic target group.

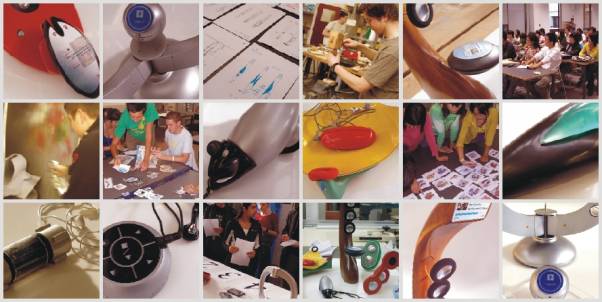

Figure 3 shows some of

the activities during the design workshop and some of the finished presentation

models of the MP3 and Speaker Unit.

Figure

3 the design workshop conducted in UK and China

Students were given

free choice as to which aesthetic group they were to produce designs for,

although we found that most students did elect for Group 1 or Group 2. The

evaluated results shown below compare the original aesthetic target, as

intended by the design students, with those that were perceived by an

independent group of students who conducted the evaluation of the finished

designs (shown in Figure 4).

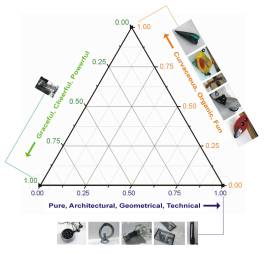

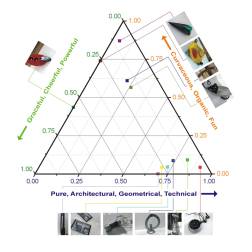

(a)

(b)

Figure 4

the comparison between the evaluation and the original targets

It is clear that most

of the designs of MP3 & Speaker are perceived to have a combination of the

three groups of aesthetic features to some extent. However, the designs for

Group 1 have most effectively matched the aesthetic target: pure,

architectural, geometrical and technical (more than 70% matching, see the

marking points in Triangle (b) for Group 1 bunched around the bottom-right

corner). The designs for Group 2 (except for one design in this group) also

have matched the target fairly well: curvaceous, organic, and fun (more than

60% matching, see the marking points in Triangle (b) for Group 2 positioned

slightly away from the top corner). As to the designs for Group 3, only one

design was selected from the very few designs in this group. Furthermore, this

design was perceived to be within Group 1 rather than Group 3. At the same

time, one design from Group 2 has been perceived to have the aesthetic features

of Group 3.

The

above results seem to imply that certain ambiguity can occur when we try to

perceive the aesthetic features of a product, where the word associations have

less correlation, e.g., in this case, graceful, cheerful, and powerful. On the

other hand, the aesthetic features that have higher correlation appear easier

to match. We may borrow a hypothesis of processing fluency of aesthetics to

explain this. Rolf Reber and Norbert

Schwarz proposed

that aesthetic pleasure is a function of the perceiver¡¯s processing dynamics.

The more fluently perceivers can process an object, the more positive their

aesthetic responses (Rolf

Reber and Norbert Schwarz, 2004). In this research case, during either the

top-down process of design following aesthetic targets or the bottom-up

process of evaluation and perception of completed designs, the more fluently

perceivers can process aesthetic features, the more effectively these features

can be applied in designs and can be perceived. Group 1 and Group 2 have the

aesthetic descriptors correlated, whilst Group 3 have non-correlated

descriptors, which may address the reason why fewer students selected Group 3

as the target for design in the first instance, as there was possibility

greater ambiguity in this category.

5. Further

research

Further research work

includes three main aspects. Firstly, to expand the product language, including

the aesthetic descriptors, to a wider range of product categories, to see what

correlation between the descriptors can be drawn and to what extent the

commonality can be found. Secondly, on a micro scale, to find how the elements

of design form, such as shape, size, colour, materials and textures,

proportion, etc correspond to each of the descriptors in product language.

These two aspects are the fundamental milestones towards the establishment of a

product language system. Thirdly, further exploration focuses on whether the

above aspects can be influenced by cultural background. This part of research

is currently on going in parallel to the first two aspects. This programme of

collaborative research is being conducted between universities in UK, China,

and Italy.

6. Conclusions

Aesthetic

experience of a designed product starts from the sensory perception between the

product and users. Product language covers the description of formal aesthetics

and the description of associations the product carries and the symbolic or

representative meanings embedded in the product. These two aspects of

description in product language system can be correlated to a certain

extent. However, the boundaries

between these two aspects can sometimes become blurred when using verbal

description. Preliminary exploration suggests some correlation between the

descriptors such as ¡®pure-architectural-geometrical¡¯ and

¡®harmonious-delicate-organic-curvaceous¡¯. Young designers tend to differ in

their abilities when manipulating the form of product to match different

aesthetic targets. However, when the aesthetic features in one product are consistently

correlated, these greater abilities seem to be evident and are facilitated more

easily.

Acknowledgement

This project was supported by the

Centre for Advanced Scholarship in Art & Design - Capability Fund,

Southampton Solent University.

Thanks

are given to Professor Cai Jun, Professor Yan Yang, Academy of Art and Design,

Tsinghua University for the arrangements of collaborative design workshop.

References

1.

Catherine Soanes, Angus Stevenson, (2004), Concise

Oxford English Dictionary, 11th Edition, Oxford University

Press.

2.

Hengfeng Zuo, Mark Jones, (2005), Exploration into

formal aesthetics in design: (material) texture, in Proceeding of 8th

Generative Art Conference, Milan. P.160-171.

3.

Dewitt H. Parker, (2004), The Principles of

Aesthetics, 10th Edition

4.

Sven Inge Braten, (2001), A Framework for Analysis

of Dynamic Aesthetics,

http://www.ivt.ntnu.no/ipd/fag/PD9/2001/Artikler/Braaten_I.pdf

5.

Paul Hekkert, (2006), Design Aesthetics: Principles

of Pleasure in Design, Psychology

Science, Volume 48, (2),

P.157-172.

6.

Joseph G. Kickasola, Cinemediacy:

Theorizing an Aesthetic Phenomenon. Baylor University.

http://www.avila.edu/journal/kick.pdf

7.

Jochem Gros, Erweiterter Funktionalismus und

Empirische Aesthetik, Braunschweig, Germany 1973.

8.

Kristin H. Lower Gautvik, (2001), Towards A

Product Language: Theories and methodology regarding aesthetic analysis of

design products,

http://design.ntnu.no/forskning/artikler/2001/Gautvik_I.pdf

9.

Susann Vihma, (1995), Products As Representations:

a semiotic and semantic study of design products, University of Art and

Design Helsinki UIAH, UIAH Information and Publishing Unit.

10. Rolf Reber, Piotr Winkielman, (2004), Processing

Fluency and Aesthetic Pleasure: Is Beauty in the Perceiver¡¯s Processing

Experience? Personality and Social Psychology Review, vol.8, no.4,

P.364-382.