Playing

Architecture with Architecture_Engine_1.0

Jochen Hoog, Dipl.-Ing.

Institute for architecture and design, Vienna University of Technology,

Austria

e-mail:

hoog@atelierprozess.net

Abstract

Architecture_Engine_1.0 is a software game installation. It’s a computer

game, where the player acts in a 3d virtual environment, like in a

first-person-view game (ego-shooter). The focus of my thesis is to show how a

game engine can be used in the architectural design process. In contrast to

modifying computer games (modding) or using them as fast real-time rendering

machines, I want to stress the possibility within game engines to run self

programmed scripts (behaviour) in a programming language.

In the game Architecture_Engine_1.0, the player starts as a human being in

the ego-perspective within a virtual space, where four objects act and react to

him and to each other. The architect can take the role of the player or even of

an object. Four simple cubes always ‘know’ where the player is and follow him.

The player is pressed for time, because he is loosing time-credits every five

seconds and only in doing something can he

gets time-credits back. The result is a reactive three

dimensional virtual architecture, within which the player can interact in

runtime.

The process of an architectural design task is

divided in two parts. The first one (design-time) is to break down the specific

design task into rules and to define the environmental conditions of the

virtual space, i.e. gravity, size, time, goal of the game, perspective of the

user etc. (That is a very useful way for an architect to handle the resources, the

time management, the planning regulations and the budget in a project.) In the

second part (runtime) the architect now becomes the player; he tries to win his

own game, he can influence the spatial events, and according to the

possibilities of a game engine he can be the user or even the architectural

object itself. The architect becomes part of an infinite, generative, and

reactive game.

The result is always different and unpredictable,

even if the basic rules are very simple. The possibility to change the

perspective in the game, which means to become even the architecture itself,

really changes the definition of an architect: Play architecture before the

game is over!

1. Introduction

In the last

couple of years the technology to create three dimensional (3D) virtual

environments has become very powerful and cheap. The evolving computer game

industry provides a wide spectrum of software tools like game engines to create

fully accessible and responsible 3D worlds rendered in real time. The focus of

this paper is on how architects can use games engines for the architectural

design process, especially to emphasize the feature of a game engine to use

self programmed scripts (behaviour) in a 3D virtual environment. In contrast to

a computer simulation a computer game is an environment which you can interact

with objects in real time, the player can be part of the 3D virtual

environment. The architect can become the architecture itself.

2. Technology - Game Engine

Game Engines

provide hardware-independent access to computer hardware such as input devices

(i.e. keyboard, mouse, and joystick), and output devices like graphic cards,

network cards, and sound cards. “A game engine

is the core software component of a computer or video game or other interactive

application with real-time graphics. It provides the underlying technologies,

(…) like a rendering engine (“renderer”) for 2D or 3D graphics, a physics

engine, collision detection, sound, scripting, animation, artificial

intelligence, networking, and a scene graph.” [1]

A 3D virtual

computer game is a real virtual world, calculated and provided within the

computer, and the game engine shows us at least 12 rendered pictures per second

(frames-per-second) on the screen of the computer, so the human eye sees a living

image of this world. Everything within this virtual environment is a computer

calculated object with certain behaviour: the objects, the light, the players,

the sound, the virtual camera, which gives the perspective into the virtual

world, and so on. They are called entities (e.g.: the entity light has the

behaviour to illuminate, the entity floor has the behaviour to be static etc.)

The virtual world itself is a three dimensional Euclidean space, which has to

be limited, because of the limited computer power. So the most virtual worlds

are big boxes.

2.1. 3DGameStudio

In the game

‘Architecture_Engine_1.0’ I used 3D GameStudio (Version 6.1). It is a computer

game development system with a model editor, world editor and a script editor

(C# - Scripting language). It provides a physics engine to create gravity and

collision detection.

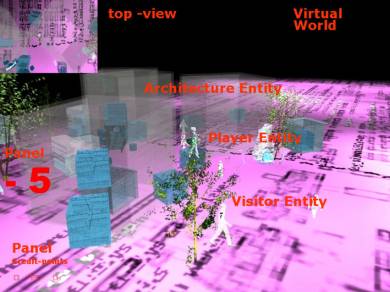

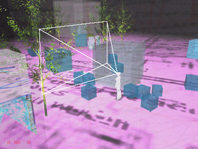

(1) Screenshot virtual world and

objects (entities)

3. The experiment -

Architecture_Engine_1.0

"I dare to predict that within 10-15 years almost all architects

offices will hire software programmers to design their own customized design

software. Animation software is out, game software is in." (Kas Osterhuis)

[2].

To examine how

a game engine can be used for a specific architectural design task, it was

decided to divide the design process into two parts: design-time and play-time.

In the design-time the designer has to break down the specific design task into

computer readable algorithms. He has to define the environmental conditions of

the virtual space, i.e. gravity, size, time, goal of the game, perspective of

the player etc. The designer has to write computer readable scripts. The design

process has to be simplified. The most important issues of the design task have

to be extracted and simulated in an abstract way. The architect has to think of

algorithms (scripts).

That can be a

very useful way for an architect to handle the resources, the time management,

the planning regulations and the budget in a project. After designing the

scripts (behaviour), they will be assigned to the objects (entities) and the

game can start.

During the

play-time the architect becomes the player; he now has to win his own game, he

can influence the spatial events; he is part of the simulation and can interact

directly within the design-space. The designer can become the user, the player,

or even the architectural object itself.

3.1. Rules

In order to

demonstrate the possibilities in general the rules were kept to a minimum. The

aim was to create architecture through the movement of the player in the

virtual game world. Also I wanted to add an element of gameplay in order to

force the player to explore the world and to force him to do something.

“Gameplay is a crucial element in any skill-and-action game. This term has been

in use for some years, but no clear consensus has arisen as to its meaning.

Everyone agrees that good game play is essential to the success of a game, and

that game play has something to do with the quality of the player’s interaction

with the game.” (Crawford) [3].

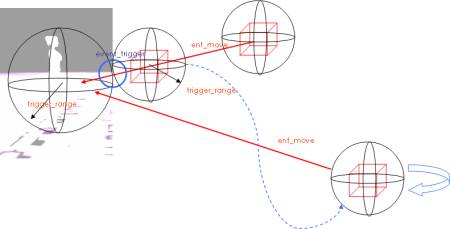

The player

starts the game as a human being (avatar) in

the ego-perspective. As in first-person-shooter games he can walk and look

around. The virtual space has an earth like gravity. From the beginning onwards

there are four kinds of simple cubes of various sizes placed around him. They

always know where the player is and follow him (which is their behaviour). If

they reach the player entity in a certain distance (collision detection) they

stop and stay there for a couple of seconds; after that they delete themselves

and are reloaded somewhere else to start the loop again.

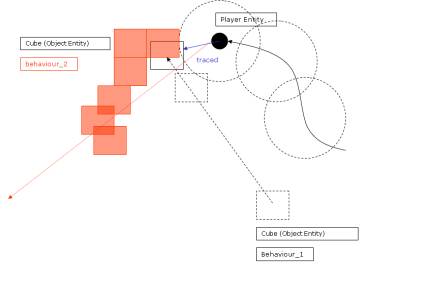

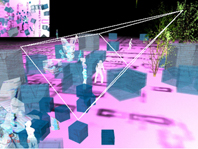

(2) Behaviour 1 - “Search and go to the player!”

(3) Result of behaviour 1

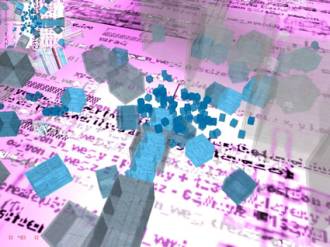

To demonstrate

the interaction between the player and the environment during the play-time,

the player is pressed for time. He starts with 100 credit points and he looses

credits every five seconds; only in doing something can he get credit points

back. The player has to activate the cubes by pressing the left mouse button at

it (like shooting). By doing so, the player changes the behaviour of the cubes.

An activated cube now has the behaviour to copy itself twenty fold in a random

direction away from the players position.

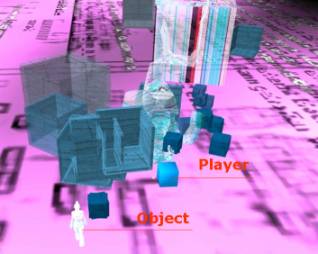

(4) Behaviour 2 - “Copy away from the player!”

(5) Result of behaviour 2

The player has

the possibility to load a prefabricated stairway and a little bridge, so he can

easily build upwards. In the virtual world are hidden some ‘invisible events’.

If the player touches them, some trees grow randomly around the player or some

virtual visitors are loaded.

(5) Result of behaviour 2

3.2. Be god, be architecture

All objects in

the virtual world are entities with behaviour. The ability to control an avatar

with the keyboard and mouse is a written script that enables this function in

the computer. This function is assigned to an object. Also the view into the

virtual world is only a kind of virtual camera which simulates a human eye. In

contrast to our world we live in, you can change these kinds of assignments in

the virtual world, which means you can look into the virtual world as an object

(third-person-view) or like a god from the sky (god-view). The control of the

movement of the human avatar (which is another script) can remain or it can be

assigned to an architectural object. So the player becomes the architectural

object, he becomes architecture.

(6) First-person view, third-person

view and god view

(7) Player is architecture

3.3 Interventions

When the game

is running (play-time) the player can only do what have been planned to be

possible within the scripts. So it is possible to replace behaviour by another,

but you can’t change the script itself. For that you have to go back to the

design-time, change the script in the script-editor and start playing again.

“Every Game has its own rules. They determine what should happen in the inner

world of a game. They are all-dominant, and no one is allowed to doubt about

the rules. Only if you are in the game, you can change them.(…) Paul Valery

mentioned in some very precise words: It is not allowed to have any kind of

scepticism about the rules in a game (…) if you brake the rules, the game

dies.” (Huizinga) [4]

3.4 Export

The game

produces virtual 3D data in real time. It is possible to ‘freeze’ the game and

export the 3D data at any moment.

3.5. Interface

The Interface

into the world is your keyboard, mouse and your screen. The player gets the

normal game like information, like the menu to save, load or stop the game, or

a display with the current credit points. On the upper left corner of the

screen the player can load a ground plan-like top view of his position in the

game world.

3.6. Too much architecture

To work with

computer based algorithms in a game engine brings up an interesting problem.

The computer throws up too many results. It is not only necessary to write

scripts to create something; you always have to limit your work, in space and

time. A virtual computer created world, is indeed a very limited thing. Within

the currently available computer power and the 3D GameStudio software, you can

provide about 300 working entities. So the architect has to think about ways of

destroying and deleting, not only of creating.

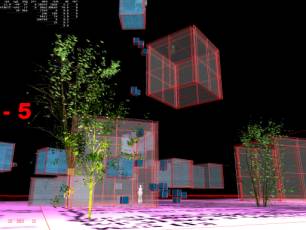

3.7. Software bugs

I had the

experience of working with scripts that can be very frustrating. Things are

right or they are wrong. There is no grey area, no in between. The

Architecture_Engine_1.0 has approximately 500 sheets of written scripts. So the

chance of forgetting one semicolon is big and because of that the game will not

start. However there is another kind of error which is more interesting. If the

game runs and everything seems to work properly, sometimes something strange

and unexpected happens. In the Architecture_Engine_1.0 the objects suddenly

start to fly. I don’t know why, I haven’t found the error; so perhaps it is

kind of an unexpected evolution. The objects behave in a new way; the reason as

yet has not been ascertained.

(8) Software error – Flying

objects

3.8. Gaming

“Denn um es endlich auf

einmal herauszusagen, der Mensch spielt nur, wo er in voller Bedeutung des

Wortes Mensch ist, und er ist nur da ganz Mensch, wo er spielt.“ (Schiller) [5]

Despite the

palpable success of computer games, questions about gaming as a cultural,

social and economic phenomenon have yet to be answered. Scientists are just starting to ask the

right questions. Brian Sutton-Smith writes: “Each person defines games in his

own way – the anthropologists and folklorists in terms of historical origins;

the military men, businessman, and educators in terms of usages; the social

scientists in terms of psychological and social functions. There is a

overwhelming evidence in all this that the meaning of games is, in part, a

function of the ideas of those who think about them.” [6]

Games are

extremely complex, in their internal structure and in the various kinds of

player experiences they create. “For hundreds of years, the field of game

design has drifted along under the radar of culture, producing timeless

masterpieces and masterful time-wasters without drawing much attention to itself

– without, in fact, behaving like a ‘field’ at all.” (Salen, Zimmermann) [7]

“A game

creates a subjective and deliberately simplified representation of emotional

reality. A game is not an objectively accurate representation of reality;

objective accuracy is only necessary to the extent required to support the

player’s fantasy. The player’s fantasy is the key agent in making the game

psychologically real.” (Crawford) [8]

Johan Huizinga

argues in his famous book Homo Ludens, that

culture always grows out of gaming “(…)

dass Kultur in Form von Spiel entsteht, dass Kultur anfänglich gespielt wird.”)

[9]

3.9. Multiplayer

One big issue

which was not tested in the experiment is the possibility within the technology

of game engines to create multiplayer environments or collaborative spaces.

MMORPG’s (massive multiplayer online role-playing games) such as Second Life or

Open Croquet are currently prospering. They provide the possibility to interact

and to communicate in a 3D virtual world.

4. Conclusions and further

work

The

Architecure_Engine_1.0 is meant to be an approach and not a ready to use tool.

The result is an infinite game. “A finite game is played for the purpose of

winning, an infinite game for the purpose of continuing the play.” (Carse) [10]

To get best

results it is necessary to alternate between the design-time and the play-time

as often as possible. And yet the result is always virtual. The architecture

becomes a playful event.

(9-10) Screenshots of the game

“Architecture

becomes a game being played by its users.” (Oosterhuis) [11] As an architect you are the designer of the rules,

you write the scripts of the game, you develop the algorithms, and finally you

play your own game. But in the game you can become everything and everybody: the

user, the planer, god or even the architecture itself. The architect becomes

programmer, player, user, god and architecture.

„It is

extremely relevant that the designers don’t just talk about the process, but

that they actually make it work. You must run the process and work in the

process.” as Kas Oosterhuis said. [11] The

outcome of the Architecture_Engine_1.0 is a reactive 3D virtual architecture,

within which the player can interact in runtime. The

architect becomes part of an infinite, generative, and reactive game. The

result is always different and unpredictable, even if the basic rules are very

simple. Play architecture

before the game is over!

5. References

[1] Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/

[2]

Oosterhuis, K. and L. Feireiss (2006). Game Set and Match II. Game Set and

Match II, Delft University of Technology, episode publishers, Rotterdam, p. 11.

[3]

Crawford, C. (1982). The Art of Computer Game Design

[4] Huizinga, J. (1938). Homo

Ludens. Hamburg,

Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag. p. 20

[5] Schiller, Friedrich (1795): Über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen.

Wohlhardt Henchmann. Fink, München.

[6] E.M. Avedon, “The Structural Eleemnts of Games”, in The Study of Games,

edited by E.M. Avedon and Brian Sutton-Smith, New York, 1971, p. 438

[7]

Salen, K. and E. Zimmermann (2004). Rules of Play – Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge,

MIT Press.

[8]

Crawford, C. (1982). The Art of Computer Game Design

[9] Huizinga, J. (1938). Homo

Ludens. Hamburg,

Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag.

[10] Carse, J. p. (1994). Finite and Infinite Games:

A Vision of Life as Play and Possibility. Reissue, Ballantine Books.

[11]

Oosterhuis, K. (2003). Hyper Bodies - Towards an E-motive architecture. Basel,

Birkhäuser.

[12] Oosterhuis, K. (2001). game set and match. game set and match, Delft

University of Technology, Faculty of Architecture, TU Delft.

Images

1-10

Screenshots

of the game Architecure_Engine_1.0