Interaction Design Patterns: Generative Design Supporting Intercultural Collaboration

N. Schadewitz,

Dipl.Des. PhD. Candidate

School of Design,

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, SAR China.

e-mail:

sd.nic@polyu.edu.hk

Abstract

Since Alexander first

introduced design patterns to architectural design, various researchers have

built on this approach to create and communicate reusable design knowledge.

Interaction design patterns for remote collaboration represent a new and constantly

evolving facet of the use of patterns in design.

So far, most collaboration

patterns address arrangements of physical objects and spaces rather than the

design of processes. In collaborative work, different teams may use different

means of communication for different purposes but there are many similarities

and commonalities among the processes employed. Patterns involved in work and

social interaction can be seen to reoccur in other modalities of collaboration

as well.

The author proposes that the

design of interfaces to support intercultural remote collaboration can be

informed by those more generalized interaction patterns. These interaction

patterns would capture and document good solutions used to structure the

collaboration process. This knowledge of interaction patterns can be reused to

generate and custom-make interface designs for various collaborative modes and

purposes.

This paper describes multiple

methods - including observations, interviews and case studies in co-located and

remote collaboration - which were used by the author to collect interaction

patterns in collaboration. It presents preliminary results in the form of

evolving interaction design patterns for intercultural collaborative learning

and design, and gives examples of how such patterns could be used to generate

designs.

1. Introduction

Design patterns and

pattern languages structure design knowledge into a format, which can be used

to generate infinite numbers of good design solutions. A pattern, which is by

definition [2] a good design solution to a problem in a certain context,

evolves slowly over generations. Patterns are written guidelines collected into

languages. There are numerous approaches to writing, sharing and using design

patterns and pattern languages in the field of interaction design, very

abstract human-computer-interaction design patterns [13], and more

contextualized interaction design [3] and website design patterns [15] to

collaborative interaction [6] and groupware patterns [12].

This paper explores the question, which pattern and pattern language

format is capable to generate good interaction design solutions in the context

of intercultural collaborative learning. It presents an interaction design

pattern approach and pattern language framework to intercultural collaborative

learning. The paper argues, that the collaboration goal and process are most

relevant to structure a pattern language for a specific context of use, but

ethnographic techniques like observations and interviews capture reoccurring good

design solutions in order to write a single pattern.

Research has been carried out to share, compare and evaluate different

approaches to pattern writing. Researchers generally agree that patterns have

to evolve slowly in order to find a commonly accepted format. But so far

researcher did not agree on a common degree of abstraction or focus of

interaction design patterns and pattern languages. However, many patterns in

the area of interactive and collaborative design remain using the original

“Alexandrian” format [2].

2. Patterns and Pattern Languages

In 1977, Alexander at al. [1] proposed a pattern language for

architecture. They argued that architecture is not created but generated by

events that reoccur, including the architecture for us experiencing it. Those

events are living patterns indirectly generated by ordinary action of people.

[2 pp.xi] Good patterns evolved slowly over generations. In order to document

good design knowledge and make it available for reuse, Alexander at al. [1,2]

collected patterns in architecture in order to abstract a shared pattern

language. This language gives each person who uses it the power to create an

infinite variety of new and unique designs. Patterns are described in

“three-part rules, which establish a relationship between a context, a system

of forces, which arises in that context [repeatedly], and a configuration which

allows these forces to resolve themselves [in a good way] in that context.” [2

pp. 247]

It sounds simple, but pattern writing is challenging. Patterns should

not be too wide or abstract, nether too limiting nor narrowing the context of

use. Alexander’s method in identifying good patterns is easy, almost profane;

You have to feel good about it! His suggestion how to identify and write

pattern reads almost like a cookbook recipe. Observe and analyze instances of

one pattern. Distinguish what feels good and bad about it. Identify and

abstract the properties all good solutions have in common. Define forces, which

balance this pattern. Describe the circumstances, which lead to a good

solution. Define a range of contexts where the named forces bring a pattern

into balance. [2 pp. 247-276] Patterns, identified in this way, slowly improve

by evaluating and testing them against our experience.

However, one isolated pattern does not work well. They need semantic

connections to other patterns. Alexander compared this phenomenon to natural

language. A word needs to be related to another word to express a deeper

meaning. Hence, a network of related patterns create a pattern language.

Alexander et al. [1] created an immense architecture pattern language offering

a network of large range (cities), middle range (buildings) and small range

patterns (single components and details of buildings). But they stress that a living

pattern language needs to be shared and needs to evolve like a culture.

Different cultures share patterns, like relatives share a common pool of genes

or natural languages share a common pool of language components. Pattern

languages vary from person to person and culture to culture, but overlaps do

occur.

3. Interaction and Collaboration Design Pattern

Interaction design patterns cover a diverse area of research into human

computer, social, collaborative or mobile interaction. Despite of writing style, naming convention, degree

of abstraction or format, different pattern collections and languages show

overlaps. Similarities of patterns can

be found between such different contexts of interaction as websites [15], human

computer systems [13] or interactive exhibits [3]. As an example, one pattern,

which reoccurs throughout the interaction design domain is called “Go back to a

save place” [13] or “Home Link” [15]. This pattern describes the phenomenon

that users want to explore the computational space freely, but in case they get

lost, users want to have a quick and secure escape, which takes them back to a

known place or position. There are more patterns showing commonalities. Those shared

patterns illustrate the emergence of a computational interface culture. Many

people share this culture nowadays. Shared patterns show a common pool of

widely accepted, good design solutions supporting a human interacting with a

computational system.

Similar to Alexander’s approach, interaction design patterns can also be

categorized into large, middle and small range patterns. As exemplified before,

small range patterns show commonalities among various interaction design

pattern collections and languages, but large range patterns differ most among

various languages. As an example, patterns like Attraction Space [3],

Commercial Website [14] or Collaborative Virtual Environment [12] closely

relate to a specific interaction design application domain, context of use and

interaction goal.

However, approaches to structure those collections and languages vary

greatly. Patterns can be structured into networks, showing relations among them

by families [12], hierarchy [14,15], or in parallel pattern languages, which

are connected by a model [3].

|

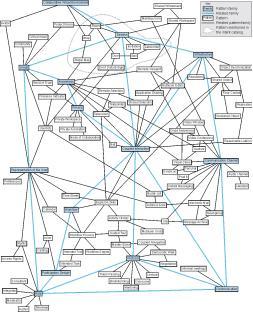

1. Groupware

Pattern Families |

2.

Shopping-Website Pattern Hierarchy |

|

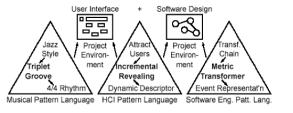

3. Model to use

parallel pattern languages |

Borchers [3] structures patterns into three separate domains to describe good solutions for interactive music exhibits. Musical patterns describe the application domain of interaction. A HCI pattern language describes the human-computer interaction structure with the exhibit. Finally, software patterns describe the computational implementation of musical and HCI patterns in the interaction process. This approach allows the integration of patterns into a very specific interaction context. Whereas Welie and v.d. Veer [14,15] established a hierarchical pattern language for website design composed of large (goal and posture), middle (experience) and small range patterns (task and action). This approach structures interaction and interface design patterns by interaction goal and process in a certain context e.g. Online Shopping [14].

Collaborative

interaction and groupware patterns cover two different interaction categories.

These collections try to relate patterns of the human-computer-interaction

domain to patterns of human-human-interaction using a computational system.

Schuemer [12] established a network of groupware pattern families, which is a

rich but no-focused collection. The collection includes any kind of

collaboration tools and artifacts, large, middle and small patterns side by

side, rather than pointing out a good collection of patterns within a specific

context. Whereas Martin’s [6-8] collaborative interaction patterns take the

entire collaborative work context into account. These patterns describe good

solutions to the organization of collaborative work activities, which have been

identified by ethnomethodologically informed ethnographic studies of work using

interactive systems. Patterns are identified as systems to structure

ethnographic material utilizing findings from field studies as recourses for

re-using in new design settings. [7]

4. Writing Pattern for Intercultural Collaborative

Learning

Several forms and modes of collaboration and collaborative leaning are

practiced in intercultural settings. Full or partial collaboration projects are

carried out in educational contexts, e-learning environments or summer schools,

using collocated, remote or mixed modes of collaboration.

On one hand, to define a framework of interaction context and goal is

most important to write patterns for intercultural collaborative learning in

the first place. On the other hand, doing ethnographic studies, observing actual

teamwork gives valuable information about intercultural collocated and remote

collaboration. As mentioned in [6-8], a design pattern is a good format to

organize, present and represent a growing corpus of ethnographic material to

outline reoccurring design solutions. Hence, I simultaneously approach writing

interaction design patterns from bottom up - identifying the single pattern,

and from top down - structuring an emerging pattern language framework.

I observe reoccurring events and processes in collaborative teamwork,

where members do not share the same cultural background. I look for overlapping

patterns of intercultural collaborative learning in varying settings. Patterns,

which occur most often, all intercultural collaborative learning contexts share.

In addition to observing single reoccurring patterns, a framework can give

guidance. For this purpose, I adapted Welie’s website design pattern framework

[14] (see figure 4). I found it very helpful to establish a pattern network,

which describes intercultural collaborative learning processes as well as

artifacts being used. Furthermore, I can relate to and extend from existing

patterns in the HCI and groupware domain.

5. Context and Methods of this Study

Pattern writing is an ongoing process of observing events that reoccur,

abstracting them into design patterns and refining those patterns by testing

them against experience. I use a human-centered research approach to identify

interaction design patterns in intercultural collaborative learning. I observed

design and accomplishment of several intercultural collaborative team projects

in various contexts. Up to now I tested a few emergent patterns in case studies

by conducting interviews and observing the collaboration process. Additionally

to those case studies, I interviewed students and users of collaborative

systems, design experts and researcher to gain an overview of practices in

related contexts to help me evaluate emergent patterns from the observations

and design case studies.

I participated in an international information design

summer academy with the topic and title "Remote Relations - Tools for

Collaboration", held by IIIDj - the International Institute for

Information Design Japan. The invited international audience from the fields of

design, business, computation and social science was composed of 20

postgraduate university students and young professionals from Japan, Korea,

Hong Kong, India, Italy, Serbia, Germany, Norway and USA. The workshop was held

in Ogaki, Gifu Province in Japan for 2 weeks in August and September 2003.

Aim of the workshop was the collaborative development

of design ideas and scenarios to support remote relationships of individuals,

companies and institutions. Participants had been split up into small teams of

four to six people with a leader for each group being assigned previously. Each

group applied different methodologies to explore this rather broad topic, such

as structured or non-structured brainstorm sessions, change of physical work

environment or modification and customization of tools and space. There were

frequent short presentations within groups and to other groups. The workshop

was structured in morning and afternoon table discussions, attended by all

participant, continuous group work and lectures by design professionals. In

addition to formal collaboration activities, participants had also been

encouraged to share daily practices, activities and functions, such as lunch,

dinner and accommodation.

In

2004, I participated in Convivio-3, the third international summer school in

user-centred interaction design, which was held in Split, Croatia. Themes of

study were “Communities in Transition” and “Sustainable Tourism”. Forty-four

students from 14 countries including Bosnia, Croatia, Slovenia, Ukraine, Romania,

Sweden, India, China and the United States participated in the 2-week program.

In addition to attending daily lecture series, participants were organized into

4 atelier groups and asked to design solutions that addressed the local

sustainable tourism needs of this post-war community-in-transition.

Each

atelier was appointed a leader, recruited in advance. Participants were

pre-assigned to the ateliers in efforts to construct teams that were well

balanced along the dimensions of culture, research discipline, and institution

of origin. Each atelier had a sub-theme, which was connected to the atelier

leaders’ areas of expertise as Mobile Devices, Design Methodologies, Identity

in Design and Games. Although the design methodologies used within the ateliers

varied, they were ethnographically inspired.

Each atelier utilized qualitative fieldwork such as interviews or

observation and did prototypes in varying degrees of fidelity to inform their

resulting designs.

Over a period of 2 years,

I observed a university design studio subject titled "Only Connect",

where students were asked to accomplish a design project collaborating remotely

and collocated. The School of Design at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University

organized and taught in collaboration with Design Schools in Korea, Austria and

USA. There were approximately 110 Hong Kong participants and 50 international

partners. Participants were undergraduate design and fine art students, from

various design disciplines and specializations including industrial,

environmental, architectural, interaction and fashion design, visual

communication and media art. They collaborated in small teams consisting of 4 -

6 people in a stream specific field over a period of seven weeks, from October

until December 2003 and 2004. Though distributed in geographical locations in

Hong Kong, Austria, USA, Japan and Korea, the meeting point was a shared

virtual project and team space in the Internet: the "Only Connect"

Project Website [www.onlyconnect.sd.polyu.edu.hk] in 2003 and a “Weblog” team

space [www.blogger.com] in 2004. In addition to the shared virtual space

students were free to use email, instant messaging, and video conferencing to

communicate remotely. In both years, Korean collaborators came to Hong Kong

over a period of about a week to collaborate collocated.

My personal agenda for

participation in the summer workshops and university courses was the

observation of co-located and remote intercultural collaboration. I looked for

practices employed to collaborate in intercultural teams within a given time

frame and local constraints. I observed teamwork strategies, and solutions to

overcome miscommunication and breakdowns in collaboration. My methods included

observation, note-taking, informal, formal and contextual interviews with the

participants, multi modal discourse analysis of online communication, and

designing prototypes and case studies in different stages of fidelity.

6. Examples of Emergent Patterns

Collaborative learning in intercultural contexts shows similarities but

also differences to previously described interaction and collaboration design

patterns. Similarities to existing interaction design patterns can be found

predominantly in small range patterns of human computer interaction and

groupware pattern domains.

Even though there are reports of using groupware applications in

collaborative learning environments elsewhere [9-10], this study cannot approve

the use of groupware especially in the context of intercultural collaborative

learning and design. I believe this finding is important as it points out the

need to support a flexible setup, as well as adaptation of work practices to

the specific context of interaction in intercultural collaboration. The

interaction domain of interaction design patterns for intercultural

collaborative learning should not be limited to groupware applications. I found

that the interaction and collaboration goal and process suggest means and

structures of interaction appropriate in the specific context. In addition to

this, my findings correspond to Graveline, Geisler and Danchak’s [4] report of

emergent patterns in media use and media richness in remote collaboration,

using predominantly emails and instant messaging as forms of group coordination

and communication. However, under certain conditions in collaborative learning

additional interaction processes including communication, coordination and

awareness mechanism need to be supported.

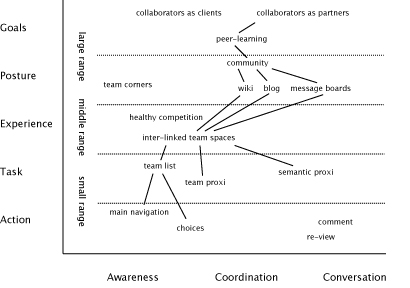

Adapting a website design pattern classification [14] I propose to

structure patterns by collaboration goal and process (goal, posture,

experience, task and action) on the x-axis, and collaboration mechanism

(awareness, coordination and conversation) identified in [9], on the y-axis,

into a hierarchical large, middle and small range patterns network. The

following graph shows a rough sketch of an evolving network of intercultural

collaborative learning design patterns using this framework. It exemplifies a

pattern connection from the collaboration goal of PEER-LEARNING to the

interaction strategy INTER-LINKED TEAM SPACES and the interface element MAIN

NAVIGATION.

This example of a pattern network and one pattern is work in progress.

4. Section of an interaction design patterns network for intercultural

collaborative learning.

Pattern Name INTER-LINKED TEAM SPACES

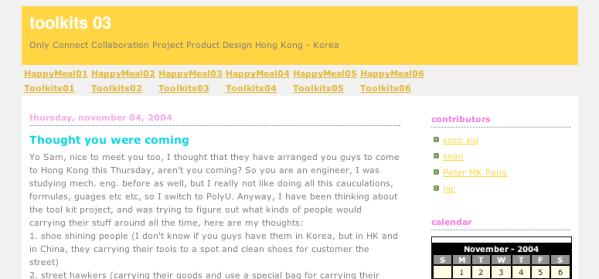

5. “Only

Connect” Collaborative Learning and Design Project, Toolkits03 Team Blog,

(http://omega.sd.polyu.edu.hk/~blog/onlyconnect/product9/)

Context

and Forces (upper

level patterns)

… your

collaborative learning environment consists of more than one team. For this

project all teams work collaboratively with their respective international team

members as partners – COLLABORATORS AS PARTNERS. In this context it is important that all teams and team members

are treated equally, and are encouraged to freely exchange any kind of

information about the project - PEER-LEARNING. You provide an online community

space to share information and comment on the team progresses– BLOG or WIKI

utilizing a remote collaboration mode. In collocated collaboration you provide

a shared physical space, which is divided into team sections or public

accessible rooms - TEAM CORNERS.

Problem

Intercultural teams profit from being aware what other teams are doing, aiming at and how they progress, especially when they work on similar projects. However, in intercultural collaboration, teams tend to focus on their potentially unfamiliar and new members within the team, missing the opportunity to share with other teams working on the same or similar topic.

Examples

Blogger.com offers the possibility to change the basic blog-page layout

within a template structure to adapt to specific needs of blog users. The

template format is based on html. Hyperlinks can be positioned at different

places on the page, linking different contents and spaces. The “Only Connect”

collaborative learning project makes use of this possibility to link different

teams in the same university collaboration course. Those hyperlinks are placed

in the main navigation space in the upper part of the website. User can browse

though other team blogs, compare the information collected and reflect on their

respective project progress. Collaboration and Communication experiences with

international team members can be viewed or directly and indirectly exchanged

in order to learn from each other’s mistakes and solutions.

Summer academies make use of available rooms and common areas in the

university environment, which usually hosts this workshop. Different

collaborating teams are placed in proximity to each other, whether in a section

within a shared room, or in public accessible team rooms. All member of the

workshop can walk into all team spaces, and share their views encouraged by the

visibility and transparency of the team’s collaboration process.

Solution (therefore)

Make a team space always accessible and easy to approach to other teams participating in the same collaborative leaning context. Provide visibly well placed connections to relate team spaces having a similar or the same topic of collaboration.

References (lower level

patterns)

In order to point out the importance of this

peer-learning option, links should be placed within an easy accessible part of

the team space – MAIN NAVIGATION.

7.

Conclusion

The applicability of those patterns is to generate different instances

of intercultural collaborative leaning environments. Environments, which

utilize remote, collocated and mixed-mode collaboration, are summer workshops,

university collaboration projects, e-learning systems and courses. A collaboration

and interaction goal and process oriented pattern language gives the designer

the power to not just to generate but custom-make intercultural collaborative

learning environments. Within my Ph.D. research, this paper presents a first

attempt to define an approach and classify a framework for such a pattern

language.

References

[1]Alexander, C. S., Silverstein,

M., Jacobson,M., Fiksdahl-King, I., Angel, S. (1977): A Pattern Language. New

York: Oxford University Press

[2]Alexander, C. S., (1979): The

timeless way of building. New York: Oxford University Press

[4]Graveline, A., Geisler,

C., Dancha, M. (2000): Teaming together apart: emergent patterns of media

use in collaboration at a distance. Proceedings of IEEE professional

communication society international professional communication conference.

Piscataway, NJ, USA

[5]Hughes, J., O'Brien, J.,

Rodden, T., Rouncefield, M. and Viller, S. (2000), Patterns of home life:

informing design for domestic environments,

Personal

Technologies, 4 (1) : 25-38

[6]Lancaster’s pattern collection:

http://www.comp.lancs.ac.uk/computing/research/cseg/projects/pointer/ethno.html

[7]Martin, D., Rouncefield, M.,

Rodden, T., Sommerville, I. and Viller, S. (2001), Finding patterns in the

fieldwork, In Proceedings of ECSCW'01,

Bonn, Germany: Kluwer)

[8]Martin, .D, Sommerville, I.

(2003): Patterns Of Cooperative Interaction – A Brief Introduction To The

Lancaster Perspective. ECSCW 2003, the

8th European Conference on Computer Supported

Cooperative Work in Helsinki, 14. - 18. September 2003. http://www.groupware-patterns.org/ecscw2003

[9]Preece. J.; Rogers, Y.; Sharp,

H. (20002): Interaction Design: beyond human computer interaction. New York,

Wiley & Son Inc.

[10]Rutkowski, A.-F., Vogel, D.,

Bemelmans, T.M.A., van Genuchten, M.: (2001): IEEE Transactions on Professional

Communication, VOL. 44, NO. 2, June 2001

[11]Rutkowski, A.-F., Vogel, D.,

Bemelmans, T.M.A., van Genuchten, M.: (2001): E-Collaboration: The Reality of

Virtuality. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, VOL. 45, NO. 4,

December 2002

[12]Schuemer, T. (2003): Evolving

a Groupware Pattern Language. ECSCW

2003, the 8th European Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Helsinki, 14. - 18.

September 2003. http://www.groupware-patterns.org/ecscw2003

[13]Tidwell,J, Common Ground

HCI pattern collection:

http://www.mit.edu/~jtidwell/interaction_patterns.html

[14]van Welie, M., van der Veer,

G.C (2003): Pattern Languages in Interaction Design: Structure and Organization. Published at In Proceedings of

Interact 2003 International Human–Computer Conference. Zuerich,

Switzerland

[15]van Welie,

M.: Interaction Design Patterns.

http://www.welie.com/patterns/index.html