Design

Precedents and Identity

Dr. K. Moraes Zarzar, MTD, PhD

Department of

Architecture, Faculty of Architecture, Delft University of Technology, Delft,

The Netherlands

e-mail: K.MoraesZarzar@bk.tudelft.nl

Abstract

Last

spring I revisited Beijing, a city that I had not seen for 16 years. I was told

of the changes that have occurred in there, but even though the city is still

overwhelming, Beijing is drastically transformed. I kept asking myself where

were those million bicycles tinkling around and where all those highways, cars

and high-rise buildings were coming from. Not much seems to remain of the

Hutong residential area except neon sights advertising restaurants and bars,

and some courtyard houses at the back of it. In fact, the monuments were the

remains of a city in radical transformation. On the one hand, millions of

Chinese might, like me, experience this radical transformation as overwhelming;

but on the other hand, they know that in many respects their quality of life is

improving with the modernization of their industry and technology, and the

modernization of their city.

This

view of a mere visitor facing this great phenomenon of growth that is China today

is the departure point of this exploratory paper where we deal with the notion

of Identity and subsequently the notions of Change and Time.

However, it is not in the scope of this paper to cover all determinant aspects involving identity. We would be satisfied if we succeed in opening the discussion about identity in the context of Generative Art and focusing on some aspects such as on morphology and society. We suggest two strategies to investigate the question; i.e. the use of design precedents (configuration and structure) as suggested by the author (Moraes Zarzar 2003) and the modernist technique of defamiliarization as suggested by Alexander Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre in their article “Why Critical Regionalism Today?” (1990). With the first strategy we bring forth the idea that precedents can be the basis of creative design, and with the second strategy, the proposal of a critical evaluation of local culture, employing modernist strategies, which could be used to create the feeling of identity above a parochial regionalism. An identity as exposed by the notion of Critical Regionalism that “should be seen as complementary rather than contradictory to trends towards higher technology and a more global economy and culture” (Tzonis, and Lefaivre 2001, p.9).

1. Introduction

During

my latest visit to Beijing, China, last April, the phenomenon of change in the

city struck my mind. During the seminar "Identity and Design" that I

attended days later in the same city, we were asked to brainstorm on the notion

of Identity, when it occurred to me that “Identity” could be understood as a

complex system, or as John Holland in his Hidden Order, How Adaptation Builds

Complexity (1995) call it: a complex adaptive system (cas).

Numerous

things crossed my mind, such as:

How

could we understand this complex system while working isolated within one of

its multi-facet parts?

On

the one hand, with the notion of identity, we might think that we are giving a

feeling of community to the inhabitants. On the other hand, identity seems to

imprison people in an unchangeable chauvinistic environment or in a parochial

picturesque regionalism. How could we deal with the dual character of Identity?

In

“Critical Regionalism”, Alexander Tzonis discusses the notion of Identity and

the modernist technique of defamiliarization as a mechanism to arrive at an

idea of Identity in design that was critically open to the import of worldwide

elements. Would this kind of technique help us to achieve a variety of high

standard worldviews against the homogenization that globalization is bringing

to us?

Would

these worldviews incite a dialog between the consumer and the buildings making

them aware of their gains and losses in this constantly changing society?

How

can defamiliarization be used as a technique to promote identity?

This

paper does not intend to cover everything that has been written about identity.

It is an explorative article that tries to model Identity from a different

angle, putting together complex adaptive systems with theoretical approaches

that take into consideration the processes of globalization and the phenomenon

of change of modern societies.

This

article discusses the notion of Identity not as a static system or closed

system, but as impregnated by the local culture, changing over time and

allowing critically evaluated influences from outside. The first part discusses

some approaches towards the notion of Identity and the second part tries to

give some insights into how a creative use of design precedents and the

modernist strategy of defamiliarization could favor the creation of places that

reflect and give continuation of people’s local culture without alienating them

from the world processes of modernization. However, one might ask why we should

bother to write about architecture and identity since so much has already

written about it. My reason to write about it and to present it during a

conference on Generative Art is to provide a means of analysis of design

products created by generative systems.

2. The Concept of Identity

What

is Identity? Next we briefly consider the notion of Identity according Manuel

Castells and the theoretical approach to regionalism according to Liane

Lefaivre and Alexander Tzonis. But before we go further in the exploration of

this notion, two things should be considered. On the one hand, the notion of

“Identity” involves numerous determinants such as those of political and social

order. As such, it seems to be a complex system, a kind of network that

stretches each time one variable changes until it either collapses or continues

to adapt as a complex adaptive system does (Holland 1995).

On

the other hand, it seems interesting to note that the notion of identity seems

to be directly opposed to the notions of change and time. However, this is not strictly

true. If a city loses its current identity, it simultaneously creates a new

one. Therefore, change in the direct environment over time is also part of the

creation of a new identity. Thus, change is part of the process of what Manuel

Castells in The Power of Identity calls “Project Identity”, as explained

below. In the case of Beijing and its inhabitants, however, one could say that

substituting the identity of their built environment that reflects their

ancient culture for a Western identity, which actually does not mean anything

to them, is anything but inspiring. The influence of the West is unavoidable,

even advantageous sometimes, but the uncritical use of Western precedents is

devoid of meaning. In Critical Regionalism, Lefaivre and Tzonis give

examples of a critical attitude toward identity that tries to synthesize the

local and global forces in architecture. But is “Identity” in modern societies

something that we should still be seeking in design?

Identity according to Manuel Castells

In

The Power of Identity, Manuel Castells names three approaches toward

Identity: “legitimizing identity”,

“resistance identity” and “project identity”.

If,

on the one hand, “legitimizing identity” is an approach “introduced by the

dominant institutions of society to extend and rationalize their domination vis

à vis social actors”, then on the other hand, “resistance identity” is

“generated by those actors who are in positions/conditions devalued and/or

stigmatized by the logic of domination, thus building trenches of resistance

and survival on the basis of principles different from, or opposed to, those

permeating the institutions of society” (Castells 1997, p. 8).

Legitimizing

identity seems to be the kind of identity that Rem Koolhaas rejects, when

making his plea for the generic city in his article “The Generic City”, because

it is a kind of identity bounded to chauvinistic ideas and nationalism.

The

third approach is that of developing a new identity. According to Castells, a “project identity” becomes real “when

social actors, on the basis of whatever cultural materials are available to

them, build a new identity that redefines their position in society and, by so

doing, seek the transformation of overall social structure” (Castells 1997, p.

8).

Identity

seems to be not easy to categorize in a society in constant transformation.

Recognizing this dynamics, Castells argues: “identities that start as

resistance may induce projects, and may also, along the course of history,

become dominant in institutions of society, thus becoming legitimizing

identities to rationalize their domination” (Castells 1997, p. 8).

This dynamics of identity refers to the phenomenon of change in society over the years. Contrary to the provocative style of Koolhaas, Castells argues that no identity has, per se, progressive or regressive value outside its historical context and shows that it is more important to know which kinds of benefits each identity brings for a specific society than to argue about the positive or negative value that each kind of identity may have.

The role of Identity in Critical Regionalism

The

notion of Critical Regionalism was introduced 25 years ago by Alexander Tzonis

to draw attention to the approach taken by a group of young German architects

in Europe. This group was working on an alternative to the postmodernism that,

with few exceptions, had not really taken architecture, as it meant to do, out

of a state of stagnation and disrepute by the reintroduction of historical

knowledge and cultural issues in design (Tzonis, Lefaivre 2003, p. 10).

The

main task of critical regionalism was, according to Lefaivre and Tzonis, “to

rethink architecture through the concept of region.” The concept of

place/region in critical regionalism is indeed fundamental to understanding the

new approach. Critical Regionalism differs from Regionalism [1] because it

“does not support the emancipation of a regional group nor does it set up one

group against another” (Tzonis, Lefaivre 1990, p. 31). Region/place does not

coincide with a nation or a territory of an ethnic group. In addition, in

Critical Regionalism, Architecture and Identity in a Globalized World, Tzonis

argues, “Whether this involves complex human ties or balance of the ecosystem

it is opposed to mindlessly adopting the narcissistic dogmas in the name of

universality, leading to environments that are economically costly and

ecologically destructive to the human community” (Tzonis, Lefaivre 2003, p.

20). In Tropical Architecture: Critical Regionalism in the Age of Globalization,

an earlier publication, Tzonis and Lefaivre also maintain, “Critical

regionalism should be seen as complementary rather than contradictory to trends

toward higher technology and a more global economy and culture. It opposes only their undesirable, contingent

by-products due to private interests and public mindlessness” (Tzonis and

Lefaivre 2001, pp. 8-9). They do not provide a checklist or a method to design

a “proper” architecture in this mode, but they give a hint by naming the

modernist technique of defamiliarization. In summary, Critical Regionalism does

not support political or ethnical issues; it refers to a balance of the

ecosystem and opposes to the destruction of the local creative potential due to

misuse of technological advances and private interests from dominant societies

in a globalization process.

As

another prominent writer on Critical Regionalism, Kenneth Frampton clearly

takes his inspiration for a critical regionalism from issues such as climate,

topography of the given site and tectonics. Frampton, argues, “Critical

Regionalism depends upon maintaining a high level of critical

self-consciousness. It may find its governing inspiration in such things as the

range and quality of the local light, or in a tectonic derived from a peculiar structural

mode, or in the topography of a given site” (Frampton 1983, p. 21).

Seeing

through both ways, the designer would provide an architecture that would

reflect the local creative potential at the same moment that it would be

critically open to trends toward higher technology and a more global economy

and culture.

Next,

we are going to take a closer look at this technique of defamiliarization and

the use of precedents.

3. Design Strategies

The

built environment is the theatre where all the determinants are influencing

each other and creating new identities over the years. In this sense, in order

to understand the dynamics of identity it would be necessary to analyze this

environment as form and structure. Second, as suggested by Aldo Rossi in The

Architecture of the City, it would be necessary to describe the

relationships between local factors and the construction of the urban artefacts

and to identify the principal forces at play in the specific location (Rossi

1966). And third, it would be necessary to apply all the methods of analysis at

hand from the social to the political, from the historical to geographic. But

as we have already mentioned, it is not in the scope of this paper to cover all

determinant aspects involving identity. We discuss the notion of identity of

buildings and their environment in relation to culture and in relation to

architects in practice. In this context, we describe two projects.

The Modernist Technique of Defamiliarization

According

to Lefaivre and Tzonis, “Defamiliarization, a concept closely related to

Brecht’s Verfremdung but also to Aristotle’s xenikon was coined by the Russian

critic Victor Shklovsky [2]. It was initially applied to literature. But it

proved to be easily applied in architecture, where it helps architecture to

carry out its critical function.”

In

Tropical Architecture: Critical Regionalism in the Age of Globalization,

Lefaivre and Tzonis argue, “Defamiliarization is at the heart of what

distinguishes critical regionalism from other forms of regionalism and its

capability to create a renewed versus an atavistic, sense of place in our time”

… “The critical approach of contemporary regionalist architecture reacts

against this explosion of regionalist counterfeit setting [as used in Romantic

regionalism] by employing defamiliarization. Critical regionalism is interested

in specific elements from the region, those that have acted as agents of

contact and community, the place-defining elements, and incorporates them

‘strangely’, rather than familiarly, it makes them appear strange, distant,

difficult even disturbing. It disrupts the sentimental ‘embracing’ between

buildings and their consumers and instead makes an attempt at ‘pricking the

conscience’. To put it in more traditional terms the critical approach reintroduces

‘meaning’ in addition to ‘feeling’ in people’s view of the world” (Tzonis and

Lefaivre 2001, pp. 8-9).

Via

defamiliarization architects can differentiate their work, and prick the

consciousness of the dweller by provoking a dialog with him/her via a

reflection that the dweller is invited to identify the known from the unknown.

The dweller remains alert to the changes, to the disadvantages and advantages

of the modern society.

To

speak about defamiliarization [3], one must first speak about the way

architects recollect precedents, and in Classical Architecture, The Poetics

of Order, Tzonis and Lefaivre show three kinds of approach: citationism,

syncretism; and the use of fragments in architectural metastatement (Tzonis and

Lefaivre 1986, p. 281). They use these approaches in combination with classical

architecture, but I will generalize them here for the recollection of any

(fragment of) precedent.

In

their analysis of these approaches, they argue that citationism is the approach

mostly taken in Kitsch architecture as well as Post-Modern architecture. With

this approach, the architect gives the viewer the sense of familiarity or

over-familiarity. It is an approach that, accordingly, alienates the dweller

from the reality of living in current modern societies, in particular in the

metropolis. A citationist approach alienates because it does not prick the

conscience of the dweller. It avoids confrontation and tries to promote a

sentimental embracing between the building and the consumer, a relation that is

broken in modernity.

The

syncretism and metastatement refer to the defamiliarization. In these approaches, fragments of physical

precedents or conceptual precedents are brought to the new design. By

defamiliarization, the fragment may mutate and be recombined with different

elements or in a different domain producing a sense of estrangement. The

intention is to provoke in the viewer [4] a kind of dialog: what is familiar

and what is strange in this new composition?

In fact, defamiliarization is not an Identity-making device. Next, we are going to see an example from Le Corbusier, the Unité d’Habitation of Marseilles, which shows what one may call a process of defamiliarization with elements far remote from the dweller. Defamiliarization, in the sense it is used in Critical Regionalism, may be seen as contributing to a “critical” identity that brings together for the dweller his local cultural values and the world-wide process of modernization. In other words, defamiliarization may be a device that helps you to evaluate the local potentials and create new worldviews without giving that alienated, over-familiarized feeling to the viewer that results in a nostalgic and parochial regionalism.

Design Precedents: Innovations vs. Continuation

Next,

we briefly describe two projects in which defamiliarization played a role: Le

Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation in Marseille, France, and MGA’s Santosh Benjamin

House in Bangalore, India. The objective is to show how both used the

defamiliarization device.

Le

Corbusier used it to come to the creation of a new housing type which reflected

the architect’s ideals for a new life-style: healthier and more enjoyable – an

innovation in the production of housing for the working class. But how was it

achieved? The author suggested in her paper “Breaking the type” (Moraes Zarzar

2003) that it was created by purposely “breaking” earlier types and taking the

fragments that would help him in creating this house for the modern man. Mathew

& Ghosh’s Benjamin House is thoroughly described and analyzed as a main

case in Shaji K. Panicker’s Master’s thesis. It is also a house composed of

fragments applied as metastatements. Their proposal seems closer to a view

grounded in the practice of a critical regionalism than to Le Corbusier’s utopian

view.

The Unité d’Habitation

Le

Corbusier’s inventions, such as Maison Dom-Ino and Maison Citrohan, combined

numerous concepts within a fascinating network that involved different levels

and domains. Concepts were carefully translated into architectural elements and

vice-versa, often evolving a (re)combination with others, such as the elements

that compose the “five points for modern architecture” or the elements of his

“architectural promenade”. Le Corbusier had a very peculiar way of looking at the

object of design: on the one hand he proceeded from extremely general concepts

trying to provide solutions for the primary needs of lodging, work, cultivation

of body and mind, and traffic; on the other hand, he claimed to have proceeded

from the concept of the kitchen as a modern hearth, from which the rest

followed naturally. This “naturally” developed design used the technique of

defamiliarization over the years using syncretism and metastatements to come to

his material.

Proceeding

from the earlier examples of transferences of the precedent features, this

section will present aspects of a possible “ontogeny” of the Unité d’Habitation

of Marseilles.

The

Grand Plan or the Ontogeny of the Unité d’Habitation

Le

Corbusier claimed that the Unité d’Habitation was the result of “40 years

gestation”. We suggest that this “gestation” was not a question of development

(ontogeny) but of lineage (phylogeny). The creation of the Unité seems to have

been the result of the use and modification of specific elements, often in

small chains of linkages over the years such as the “five points for a modern

architecture”, or Le Corbusier’s bottle, bin and bottle rack (linked features).

Le

Corbusier’s task was to provide a housing scheme for workers in the bad

economic situation after the Second World War in France. His solution grouped

330 units to house a community of roughly 1600 inhabitants in an 18-storey

building providing extensive services to the community. This was a unique

opportunity to put all his ideas concerning multi-family housing schemes into

practice. He had already developed the Maison Dom-Ino, the Maison Citrohan and

the Immeubles Village as well as concepts at city planning level such as the

concept of the “vertical garden city”. The Unité d’Habitation for the workers

of Marseilles was the result of all these studies. In designing the Unité, he

had certainly recalled many of those concepts; some of a general order (light,

sun, greenery) but also others that could be more straightforwardly translated

into architectural elements (the piloti, the roof garden, the free façades, and

so forth).

In

fact, many parts of this building block were already developed in detail

through experiments in other designs. However, before he could use these

precedent features, he needed to have an overall framework. Le Corbusier had to

assemble the right features into a whole to match the new desired

configuration. In his world full of metaphors, he then placed bottles

(dwellings) into the bins (neutralizing walls) and the bins into the bottle

rack (structural framework); a collective roof garden on top of the structure

with activities for all inhabitants, and a piloti freeing the whole block from

the humid ground, providing the whole community with parks, schools and other

extensions of the home and freeing the landscape/ horizon of obstacles at

ground level.

It

was not only a question of assembling the existent elements, i.e. recalling

them and putting them together. They needed to be adapted to the new

constraints and available technology. Due to these constraints and

possibilities, “mutations” occurred.

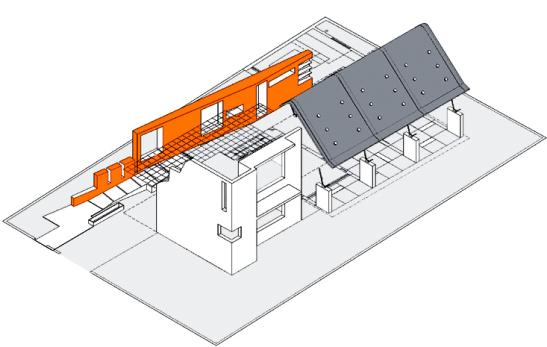

The

roof garden, the bottle rack and piloti gave the primary or general structure

of the Unité (Figure 1). This primary framework enabled Le Corbusier to use

many of his precedents, some of them with further “mutations”.

Some

features changed their physical expression, i.e. their pattern or structural

configuration changed as, for example, the slender piloti of the houses of the

1920s changed into the gargantuan piloti of the Unité. Other features changed

from domain level, meaning that the resultant element acquired uses different

to the original one. For example, the roof garden was originally a family

garden, but it changed into a community garden after its recombination with the

deck of the ocean liner (a precedent of a later date than the vernacular houses

of Istanbul). It became the square, the club, and the gymnasium of the building

block community. In other words, some of the linked “five points of a modern

architecture” from 1927 were used in a “mutated” form. The initial linkage was

broken; some features “mutated”, and were recombined and re-used in the Unité.

This is also the act of defamiliarization.

The

free façade concepts also changed their domain level: from the private (the

dwelling) to the collective (the building). The free façade concept was

initially tried out at the level of a (Citrohan) house as well as at the level

of the apartment unit of his theoretical multi-family building, and then to a

free façade at the level of the building block, where the façades of the

apartment units are standard and its freedom resides in the combination of the

parts to make the whole.

Through

our observation, we may say that Le Corbusier made ample use of the technique

of defamiliarization, but his purpose was to provide a new lifestyle. The

fragments of the past were “collected” all over the world, from the savage hut,

the vernacular houses of Istanbul, to the ocean liner; but also from things

that people do not quite relate to a dwelling, such as the bottle and the

bottle rack.

We

have shown that Le Corbusier used the process of defamiliarization in such a

way that one could speak of a lineage or phylogeny of precedents which were

continuously changing and recombining.

We have also shown that in the development of a specific project, the Unité d’Habitation of Marseille, that Le Corbusier took his five points for a modern architecture out of its linkage, mutated some of them and afterwards recombined it. In a form of syncretism he used a bottle rack, the roof garden and the piloti to provide an overall frame. He invented a new type, a building to fulfill his utopian view of a new lifestyle for modern man. In other words, he was in a process of creating a new identity and his precedents were not based on material collected in the region but from all over the world.

Fig. 1: Citrohan house vs. the unité

d’habitation, decomposing and recombining the 5 points for a modern

architecture

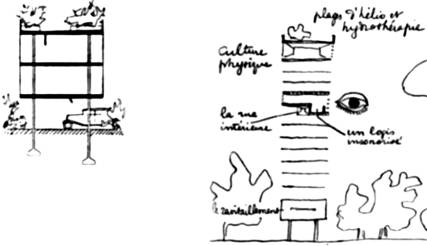

MGA’s Benjamin House

According

to Shaji K. Panicker, Nisha Mathew-Ghosh and Soumitro Ghosh completed Dr.

Santosh Benjamin House in 2000-2001 to be built in Bangalore, India. They used

fragments of design precedents and used the technique of defamiliarization.

With

Dr. Santosh Benjamin House, we study one isolated project and not the oeuvre of

Nisha Mathew-Ghosh and Soumitro Ghosh (from the firm MGA). What interests us

here is the difference in approach. Mathew and Ghosh were not constructing a

house for a “utopian modern man” but for a real person of Bangalore. Mathew and

Ghosh seem to bring together tradition, but through a critical analysis that as

a mechanism could be compared with defamiliarization, as well as all modern

techniques and materials available. Mathew and Ghosh seem to work in a continuous

dialectical manner. They used traditional configurational precedents that

embedded a nostalgic life style and tried to fit them in the lifestyle of a

particular family living in Bangalore.

Mathew

and Ghosh seem to come to their material by fragmenting traditional and

vernacular houses from India, in particular from the region. Panicker claims

that “fragmenting and transforming the elements effectively springs from MGA’s

understanding of the shift, taking place in contemporary society away from the

traditional, resulting in the feeling of losing not only one’s identity but

also identity constructions occurring in architecture.” By analyzing

traditional houses in such a way, they come with fragments that, after a

confrontation with life in contemporary society, can be introduced in their

designs in a totally novel relation to other elements. Based on the analysis

that Shaji K. Panicker made of Benjamin House for his Master’s thesis, I will

describe the main points concerning the verandah.

The

verandah of the post-colonial society had a relation to the street, was one of

the elements. Due to the confrontation to life in the city in Bangalore, this

element is replaced to face a more private garden. In the place where the

verandah would traditionally be placed, one may find a stark wall that makes

clear the boundary between public and private. There, behind this stark wall,

begins the private life, away from the busy street life, a stark wall that work

as Adolf Loos’ concept of the mask.

In

the same fashion, and according to Panicker, “the form of the canopy, above the

re-located veranda or sit-out, is reminiscent of the pitched roofs of south

Indian vernacular architecture. The idea behind lifting the canopy above the

solid masonry of the rest of the building is to give the building a sense of

lightness. This sense belies the pressures of globalization by allowing such

pressures to flow through, like local air and weather patterns sometimes

supporting them, sometimes resisting them”.

According to Panicker, “The canopy roof is suggestive of a regional tradition [vernacular houses of Bangalore] but resembles it in a way that is not at all traditional; neither in its materiality, nor in its connection with the rest of the house.” He argues, “the canopy reflects globalization in an implicit manner, and questions regionalism per se. The regional element is seen to be incorporated strangely, rather than familiarly, obeying one of the precepts of Tzonis and Lefaivre’s Critical Regionalism. Formally the roof lifts away from the sit-out below, floating in the space between the garden and the house.” In summary, the canopy is a precedent recollected in its configuration but not in its tectonics.

Fig. 2: Benjamin House, recombination

of elements from traditional India and the modern cities

Conclusions

After

Castells’ definitions of identity and Lefaivre and Tzonis’ arguments towards a

Critical Regionalism, we focused on the use of precedents and on the notion of

defamiliarization to explore the notion of identity in a society facing

globalization and international interventions.

At

the beginning of this article, I posed five questions concerning: how we could

understand Identity as a complex system while working isolated within one of

its multi-facet parts; how we could deal with the dual character of Identity;

whether defamiliarization was a technique to help us to achieve a variety of

high standard worldviews against the homogenization that globalization is

bringing to us; whether these worldviews would incite a dialog between the

consumer and the buildings, making them aware of the potential alienation that

they could be living in; and finally, how defamiliarization could be used as a

technique to endorse a kind of critical identity which would take into

consideration creative local potential.

Defamiliarization

seems to play an important role in creating worldviews such as in the case of

Le Corbusier’s Unité and MGA’s Dr. Santosh Benjamin House. In both cases, the

defamiliarization is far from citationism and closer to syncretism and

metastatements. Their projects carry meaning and feeling in their expression.

However, it seems that the recollection of MGA’s precedents, in particular the

verandah, carries more meaning and feelings for the dweller than Le Corbusier’s

precedents used in the Unité would ever do for the dwellers of the Unité. In

the case of Benjamin House, one can speak about a critical regionalism and

subsequently about the creation of an identity of resistance against the

homogenization of design and of our cultures; an identity that has a

dialectical relation with processes of modernization.

How

could we understand Identity as a complex system while working isolated in one

of its multi-facet parts? It is not in the scope of this paper to develop a

system to analyze which role identity plays in society. But returning to our

statement that identity is a complex adaptive system, we could have a quick

look into my initial assumption that Identity is a complex system. In Hidden

Order, How Adaptation Builds Complexity, John Holland explores the

characteristics of complex adaptive systems (cas) to “carry out thought

experiments relevant to all cas” (Holland 1995, pp. 37-38). John

Holland's most renowned discovery is Genetic Algorithms; GAs that theoretically

allow computer modeling of "complex adaptive systems" (cas) via an

array of "agents" in learning systems, despite the fact that

important learning in the real world is neither narrowly sequential nor

short-looped. Therefore, we open here the discussion of whether there could be

a possibility of developing a GA or GP system that could provide us with a

deeper insight into the relation between identity, architecture and the city or

at least to allow architects in practice to work within this context.

Holland

argues that all complex systems, that he called complex adaptive systems (cas),

share seven basic (modelable) characteristics, which are crucial elements of

real-life learning systems. He named four properties and three mechanisms,

namely: Aggregation (property), Tagging (mechanism), Non-Linearity (property),

Flows (property), Diversity (property), Internal Models (mechanism), and

Building Block (mechanism). Holland maintains that the selection of those

characteristics were, in part, a matter of taste, but he says that all the

other candidates could be ‘derived’ from an appropriate combination of these

seven basics. Turning to Identity, one may observe that it refers to the notion

of place, to people (group or individual), to culture, to a man-made

environment. People speak about the identity of a particular city, of a

building, of a religious group or of an institution, and so forth. They

together form a network that, we assume, can represent a cas system.

Using

Aldo Rossi’s method as set out in The Architecture of the City, one

could describe issues concerning a city and its individuality. A more detailed

analysis of this method would show whether one could match Rossi’s concepts

with the aforementioned complex adaptive system and see whether Holland’s basic

terms could be useful for the analysis of the effectiveness of real-world

systems involving the notion of Identity. Would Rossi’s method help us to grasp

the cultural issues that pervade the architecture of a specific place? What we

have now are “empty boxes” of Holland’s and Rossi’s method and only by carrying

out case studies could one determine whether the notion of identity could be

modelable or not in a sense to help architects in practice in using design

precedents in a kind of “project identity”.

This

article maintains that only by understanding the complexity and the dual

character of the notion of Identity, can one create worldviews that prick the

consciousness of the dwellers and above all do not discard the local creative

potentials in favor of a shallow, homogenized world.

Notes

[1]

In Lefaivre and Tzonis’ “Critical Regionalism”, Tzonis presents a history of

Regionalism applied to architecture. He argues, “it was the Greeks that in the

context of the politics of control and competition [Castells’ “legitimising

identity”] between their polis and their colonies used architectural elements

to represent identity of a group occupying a piece of land”. Tzonis draws the development of Regionalism

in history passing through Vitruvius to the “narcissist Heimatarchitektur”

until its shift in the beginning of the 20th century by Mumford.

About

this shift Tzonis argues, “It was by reframing the notion of regionalism with

his notion of ecology as well as his association with humanist, universalist

and rationalist ideas of the physiocrats and the Enlightenment that he

[Mumford] reinvented regionalism, identifying in relation to it technocracy and

bureaucracy as the new imperial forces and defining the emancipated state for

independence as one governed by economic rationality, ecological sustainability

and community. Therefore, his notion of regionalism was detached from its

nationalist bias” (Tzonis, Lefaivre 2001, pp. 6-7).” Mumford, according to

Tzonis, “succeeded in savaging the concept of regionalism from commercial and

chauvinistic abuse and in reframing it in a new context relevant to new

realities of the time, relating it to economic and environmental costs of the

misuse of resources” (Tzonis, Lefaivre 2001, p. 19). Mumford’s reference to

Regionalism involving ecological sustainability and community seems to impose

equilibrium between a “legitimising identity” as well as a “resistance

identity”.

[2]

According to Lee T. Lemon and Marion J. Reis, "The purpose of art,

according to Shklovsky, is to force us to notice. Since perception is usually

automatic, art develops a variety of techniques to impede perception or, at

least, to call attention to themselves.

Thus Art is a way of experiencing the artfulness of an object; the

object is not important."… "To the extent that a work of art can be

experienced, to the extent that it is, it is like any other object. It may

'mean' in the same way that any object means; it has, however, one advantage -

it is designed especially for perception, for attracting and holding attention.

Thus it not only bears meaning, it forces an awareness of its meaning upon the

reader. Although Shkolvsky did not follow this line, it does widen the range of

his theory without inconsistency. He

prefers to argue, as does I. A. Richards, that perception is an end in itself,

that the good life is the life of a man fully aware of the world." …

"According to Shklovksy, the chief technique for promoting such perception

is defamiliarization. It is not so much

a device as a result obtainable by any number of devices. A novel point of view, as Shklovsky points

out, can make a reader perceive by making the familiar seem strange." -

Lee T. Lemon and Marion J. Reis. 1965. “Introduction”. In: Russian Formalist

Criticism: Four Essays. Edited by: A. Olson. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, pp. 4-5.

[3]

The use of fragments of design precedents or conceptual precedents takes me to

the use of mimesis in Hilda Heynen’s Architecture and Critique. The meaning of

Mimesis changed over the centuries from pure imitation (Mimesis means imitation

in Greek) to a device in Adorno’s Aesthetical theory that has a dialectical

relation with his notion of negativity to endorse the critical character of

art. For Adorno, mimesis “is a kind of affinity between things and persons that

is not based on rational knowledge and which goes beyond the mere antithesis

between subject and object.” In other words, mimesis means analogy and is based

on analogical reasoning. As analogy it is based on similarities, structure and

purpose, however, Adorno seems to be more interested in making room for “the

nonidentical and the opaque”. According to Heynen, Adorno is convinced that

“the mimetical potential of art, if it is rightly applied – ‘right’ not in

political but in disciplinary, artistic-autonomous terms - vouches for its

critical character, even apart from the personal intention of the artist. Works

of art yield a kind of knowledge of reality. This knowledge is critical because

the mimetical moment is capable of highlighting aspects of reality that were

not perceivable before. Through mimesis, art establishes a critical relation

with social reality.” (Heynen 1999, pp. 183-188) Would mimesis mean

defamiliarization in the sense proposed in Critical Regionalism, which by

syncretism and metastatement creates “meaning in addition to feeling in

people’s view of the world” (Tzonis and Lefaivre 2001, p. 9)?

[4] “If the whole complex lives of many

people go on unconsciously, then such lives are as if they had never been.”

Tolstoy quoted by Alexander Tzonis and Liane Lefaivre. 1986. Classical

Architecture, The Poetics of Order. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT

Press.

References

Castells, Manuel. 2004. The

Power of Identity. In: The Information Age, Economy, Society, and Culture. Volume II.

Frampton, Kenneth. 1983. “Towards a

Critical Regionalism, Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance”. In: The

Anti-Aesthetic, Essays on Postmodern Culture. Edited by: Hal Foster. Port

Townsend, Washington: Bay Press

Heynen, Hilda. 1999. Architecture

and Modernity, a critique.

Cambridge, Massachusets: The MIT Press

Holland, John. 1995.

Hidden Order, How Adaptation Builds Complexity. Reading, Massachusetts:

Perseus Books

Koolhaas, Rem; Bruce Mau;

Hans Werlemann. 1998. “The Generic City”. In: S,M,L,Xl. Monacelli Press

Lee T. Lemon and Marion J.

Reis. 1965. “Introduction”. In: Russian Formalist Criticism: Four Essays.

Edited by: A. Olson. Lincoln and

London: University of Nebraska Press

Moraes Zarzar, K. 2003. Use

& Adaptation of Precedents in Architectural Design: Toward an Evolutionary

Design Model. Delft: Delft University Press

Panicker, Shaji K. year. Implicit

Metastatements, Domestic signs in the architecture of Mathew and Ghosh Archits,

India. Http://www.layermag.com/shaji.pdf

Rossi, Aldo. 1966. L'

architettura della città. Padua: Marsilio Editori

Tzonis, Alexander and Liane

Lefaivre. 1986. Classical Architecture, The Poetics of Order. Cambridge,

Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Tzonis, A., and Lefaivre, L.

(co-author). 1988. “Metafora, memoria e modernità”. L'Arca. March 1988,

pp. 4-12 – Case study on the use of analogical thinking and metaphor in design.

Tzonis, A., and Lefaivre, L.

(co-author). 1990. “Why Critical Regionalism Today?” A & U. no.5 (236).

May 1990. pp. 23-33

Tzonis, Alexander and Liane

Lefaivre. 1996. “Critical Regionalism”. In: The Critical Landscape. Edited by:

A. Graafland and Jasper de Haan. The Stylos Series. Rotterdam: OIO Publishers

Tzonis, Alexander and Liane

Lefaivre. 2001. “Chapter 1: Tropical Critical Regionalism: Introductory

Comments”. In: 2001. Tropical Architecture: Critical Regionalism in the Age

of Globalization. Edited by: Alexander Tzonis, Liane Lefaivre and Bruno

Stagno. Wiley-Academy.

Tzonis, Alexander and Liane Lefaivre.

2003. Critical Regionalism, Architecture and Identity in a Globalized World.

Munich; Berlin; London; New York: Prestel.

The Author: In 1985, Karina Moraes Zarzar

obtained her Bachelor’s degree in Architecture at the UFPE University, Brazil.

Between 1989 and 1991 she followed the OPB post-graduate course at Delft and

Eindhoven Universities of Technology in The Netherlands and obtained the title

Master of Technological Design (MTD). On June 11th, 2003, she received her

doctoral degree at the Delft University of Technology, and is currently

lecturing and conducting research at the same university.