MATHLAND

From

Topology to Virtual Architecture

Prof.

Michele Emmer

Dipartimento di

Matematica "G. Castelnuovo",

Universitŕ di Roma

"La Sapienza"

email:

emmer@mat.uniroma1.it

Abstract

The aim of the paper is to investigated in order to

understand, at least partly, how philosophical, artistic, scientific and, in a

word, cultural elements have contributed throughout the centuries to the

synthesis of a project such as that for Hellenic civilisation for the town of

Athens. A sort of voyage to the inside of western culture of the past two

millennia, highlighting from my point of view the cultural aspects associated

to geometry, mathematics and architecture.

Foreword

A few days before finalising this paper, I visited

the 2004 Biennale di Architettura in Venice. The theme of the Biennale was

Metamorph and many of the exhibitions

were very relevant to the paper that I was writing. I did not have the time to

rewrite entirely my article, but I wanted to add a brief foreword to it.

"Many of the great creative acts in art and in

science can be seen as essentially metamorphic as they entail the conceptual

shift of the organising principles from one area of human activity to another

visual analogy. To see something as essentially similar to another has been a key

tool in the evolution of the forma mentis

in every field of human research.

I used the term

structural intuitions to try to

capture my feeling regarding the way in which these conceptual metamorphoses

work in visual arts and in science.

Is there anything that creates a common ground

between the creators of works of art, the artists, and the scientists regarding

impulse, curiosity, desire to generate images either communicative or

functional of what they see and try to understand?

The term

structural intuitions tries to capture what I wanted to say in one

phrase, i.e. that sculptors, architects, engineers, designers and scientists

frequently share a profound awe regarding the magical structures that emerge

from nature's configurations and processes, both simple and complex. I believe

that people derive deep satisfaction from the perception of order within chaos

and that this satisfaction comes from the way in which our brains extract

inherent patterns, static and dynamic."

So writes

Martin Kemp, art historian specialised in the relationship between art and

science in the article "Structural

intuition and metamorphic thought in art, architecture and science" in the volume "Focus", [1] of the

catalogue of the International Exhibition of Architecture in Venice 2004.

Dedicated to the theme Metamorph . Kemp refers mostly to architecture, while

Kurt W. Forster, the curator of the exhibition, discusses of variants developed

through technological innovation, of continuous surfaces in transformation, of

great complexity and large numbers

He cites the mathematician Ian Stewart's article titled "Nature's numbers: discovering order and Pattern in the Universe" (1995). Key words: pattern, structure, order, metamorphoses, variations, transformations, mathematics. These words, projects and ideas present at the Biennale 2004 were visually linked to what I wanted to write regarding the link between mathematics, architecture, topology and transformation. These words, projects and ideas are in continuity with the preceding 2002 Biennale, my starting point. This is why I have added this brief foreword.

Introduction

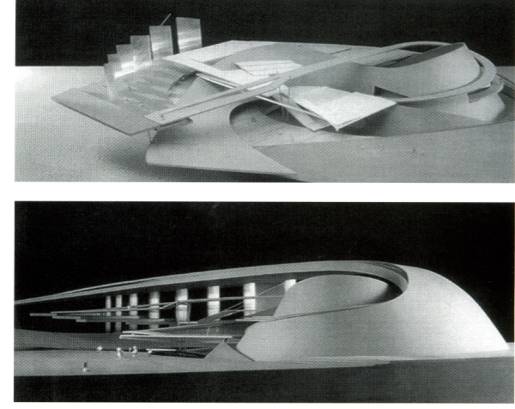

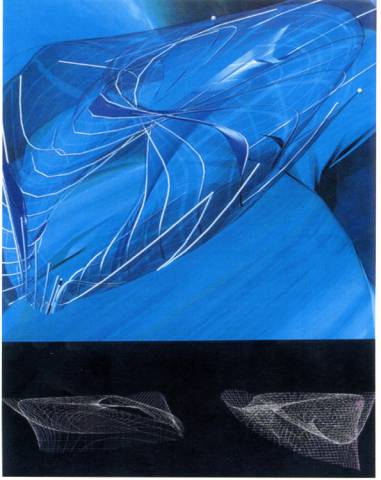

In the summer of 2002 the Biennale di Architettura

was held in Venice. Among the many projects and ideas on show, some very

interesting, others merely more or less extravagant, was the project for a

museum of the Hellenic world from a group of architects called Anamorphosis

Architects, comprised of Nikos Georgiadis, Tota Mamalaki, Kostas Kakoyiannis

and Vaios Zitounolis. A project that places a great emphasis on the spatiality

of the construction, it has a large open and continuously evolving space, with

those curved lines that twist into contorted spirals, and in the centre, right

at the centre of a great spiral, the expository heart of the classic period of

Greek civilisation. That building was, in some sense, the start and (temporary)

end of a discourse that began with Euclidean geometry thousands of years ago.

Fig.

1 Anamorphosis Architects, Athens, Greece, Project for the museum of the

Hellenic world (2002), © Anamorphosis Architects

It was a geometry that, together with Greek

philosophy, was at the heart of the foundation of western civilisation, as we

now know it. Obviously, let us not forget the influence of other civilisations,

above all the Islamic one, which has allowed Europe to rediscover the forgotten

Greek civilisation. There are several questions that must be investigated in

order to understand, at least partly, how philosophical, artistic, scientific

and, in a word, cultural elements have contributed throughout the centuries to

the synthesis of a project such as that for Hellenic civilisation. A sort of

voyage to the inside of western culture of the past two millennia and more,

highlighting from my point of view the cultural aspects associated to geometry,

mathematics and architecture.

Space and

Mathematics

In the

years between 1830 and 1850, Lobacevskij and Bolyai constructed the first

examples of non-Euclidean geometry, in which Euclid's famous fifth postulate on

parallel lines was not valid. Not without doubts and deliberations, Lobacevskij

was to call his geometry imaginary geometry

(nowadays called non-Euclidean hyperbolic geometry), it was so counter to

common sense. Non-Euclidean geometry remained a marginal aspect of geometry for

several years, a sort of curiosity, untill it was finally incorporated into

mathematics as an integral part via the

far-reaching ideas of G.F.B. Riemann (1826-1866). In 1854 Riemann

brought before the Faculty of the University of Gottingen the famous dissertation

entitled Ueber die Hypothesen, welche der

Geometrie zur Grundeliegen (On the Hypotheses which lie at the Bases of

Geometry), that was to be published only in 1867. In his presentation, Riemann

upheld a global vision of geometry as the study of varieties in any number of

dimensions, in any number of dimensions, in any kind of space. According to

Riemann's ideas, geometry need not necessarily deal with points or space in the

ordinary sense, but sets of n-ple coordinates.

On

becoming a professor at Erlangen in 1872, Felix Klein(1849-1925) in his

inaugural speech, known as the Erlangen

Program, described geometry as the study of the properties of shapes that

have an invariant character with respect to a particular group of

transformations. Consequently every classification of the groups of

transformations becomes an encoding of the different geometries. For example,

the Euclidean geometry of the plane is the study of the properties of shapes

that remain invariant with respect to the group of rigid transformations of the

plane, comprised of the set of translations and rotations.

The

official birth of that branch of mathematics now called Topology is due to Poincaré, in his book Analysis Situs, a Latin translation of a Greek name, published in

1895: "As regards me, all the different research I have undertaken has led

me to Analysis Situs (literally Analysis of Position)."Poincaré defined

Topology as the science of understanding the qualitative properties of

geometric shapes not just in ordinary space but also in space of dimensions

greater than three.

Adding

to all this the geometry of complex systems, the geometry of fractals, chaos

theory and all the 'mathematical' images discovered (or invented) by

mathematicians in the last thirty years using computer graphics, we can easily

understand how mathematics has contributed crucially to changing our notion of

space many times over, both the space we live in and the notion of space

itself.

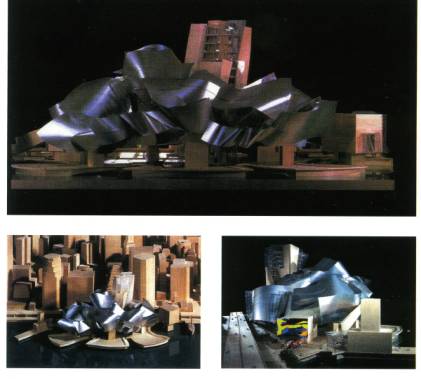

This is particularly so as regards Topology, the science of transformations. See for example Frank O. Gehry's project in New York for the new Guggenheim museum in Manhattan, an even more provocative, even more topological project than that of the Guggenheim in Bilbao. The cultural leap is certainly remarkable; building with technologies and materials that allow us to effect a transformation, making the building nearly continuous, a kind of contradiction between the final construction and its deformation.

Fig. 2 Frank O. Ghery Project for the new Guggenheim museum in Manhattan. Courtesy of © Keith Mendenhall for the Gehry Partners Studio.

It

is an interesting sign that one has started to study contemporary architecture

using the tools that mathematics, that science has provided, cultural tools as

well as technical ones.

Like

every good journey, we need to trace a route, a route that will include the

elements used to make sense of the word space.

The

first element is, without shadow of a doubt, the space that Euclid came to

outline with definitions, axioms and the properties of objects that were to lie

in that space. The space that would be the one of perfection, Platonic space.

Man as origin and measure of the universe, a notion that transcends centuries.

The mathematics, the geometry that has to explain everything, even the shape of

living things: The Curves of Nature,

the title of a famous 20th Century book by Cook, which one certainly could not

have imagined to be so true, finding in the shapes of nature as it does, even

in those right at the origin of life, several mathematical curves. From the

famous book by D'Arcy Thompson, On Growth

and Form of 1914 to René Thom's catastrophe theory, to complexity and the

Lorentz effect and non-linear dynamical systems.

The

second element is liberty; mathematics, geometry would seem to be the kingdom

of dull. Anyone who has never practiced mathematics, who has never studied

mathematics at school with interest, will never manage to understand the deep

emotion that mathematics can inspire. Nor can these people understand that

mathematics is a highly creative activity. Moreover, since in many cases

mathematics does not require huge financial resources, one can rightly say that

mathematics is the kingdom of liberty and fantasy. And certainly of rigour. And

correct reasoning.

The third element on which to reflect is how all

these ideas are communicated and assimilated, hopefully not buried deep and

only heard of by different sectors of society. The architect Alicia Imperiale

wrote in the chapter Digital Technologies

and New Surfaces of the book New

Bidimensionalities [2]: "Architects freely appropriate specific

methodologies from other disciplines. This can be attributed to the fact that

broad cultural changes are verified quicker in other contexts than in

architecture." She adds:

"Architecture

reflects the changes that occur in culture, albeit many feel at a painfully

slow pace. [...] In constantly seeking to occupy an avant-garde role,

architects think the information borrowed from other disciplines can be rapidly

assimilated into architectural design. Nevertheless, this `translatability',

the transfer from one language to another, remains a problem. [...] Architects

more and more frequently look to other disciplines and industrial processes for

inspiration, and make ever greater use of computer design and industrial

production software originally developed for other sectors.

Later

on, Imperiale recalls, "it is interesting to note that, in the information

era, disciplines once distinct are now linked to each other through a universal

language: the digital binary code." Does the computer resolve all

problems?

The

fourth element is the computer, the graphic computer, the logic machine and

geometer par excellence. The idea of an intelligent machine realised, a machine

capable of attacking the widest range of problems, if we are able to make it

understand the language we are using. The inspired idea of a mathematician,

Alan Turing, brought to fruition by stimulus of a war. A machine built by man,

into which has been inserted a logic also built by man, thought up by man. A

very sophisticated tool, irreplaceable, not just for architecture. Precisely

that, a tool.

To summarise, the journey unwinds through the words computers, axioms, transformations, words, liberty. One word will have a great importance in this journey for the idea of space: Topology. For the other aspects I refer to the book Mathland: from Flatland to Hypersurfaces.[3]

From Topology to Virtual Architecture

"Around

the middle of the 19th century, geometry began to develop in a completely

different

way

that was destined to quickly become one of the great forces of modern

mathematics." The words of Courant and Robbins in their famous book, What Is Mathematics. This new field,

called analysis situ or topology, has as its object the study of the property

of geometric figures that persist even when the figures undergo deformations so

profound as to lose all their metric and projective characteristics."

Topology,

then, has as its subject the study of those properties of geometric shapes that

remain invariant when the shape is subjected to deformations so complete as to

lose all their metric and projective properties, such as shape and dimension.

That is, the geometric shapes retain only their qualitative properties. Think

of shapes made of an arbitrarily deformable substance that can be neither cut

nor soldered; the properties are those that are preserved when one arbitrarily

deforms a shape so constructed.

In

1858 the mathematician and astronomer August Ferdinand Moebius (1790-1868)

described for the first time a new surface in three-dimensional space in a work

presented to the Academy of Sciences in Paris, a surface now known as the

Moebius strip. In his work, Moebius had described how it is possible to easily

construct the surface that now bears his name: take a rectangular strip of

sufficiently long paper. If A, B, C, D indicate the vertices of the rectangle

of paper, proceed as follows: holding one end of the strip still with one hand

(AB for example), perform a twist of 180° on CD along the horizontal axis of

the strip so as to make A meet D and B meet C. The construction of the Moebius

strip is complete! The surface has been deformed, without cuts or tears, and

the rotation performed on one end of the strip has profoundly altered its properties.

One consists of the fact that if you trace along the longest axis with a

finger, you realise that you run the whole length and return to exactly where

you set off, without having to cross the edge of the strip; the Moebius Strip

has therefore only one single side, not two, an inside and an outside like a

cylindrical surface has, for example. If you wanted to paint the surface of the

strip, proceeding along the horizontal axis, it is possible to colour the whole

surface without ever lifting the brush and without crossing the egde of the

surface. To perform the same operation with a cylindrical surface, you could

start with the outside face, but to paint the inside one too you'd have to

cross one of the two edges that separate the outside face from the inside face,

something you don't have to do for the Moebius strip. While for the cylindrical

surface, if you run a finger along the upper edge you never reach the lower

edge, in the case of the Moebius strip if you start from any point on the egde

you follow the whole edge and come back to where you started, so therefor it

has only one edge. All this has

important repercussions from a topological point of view: among other

things, the Moebius strip is the first example of a surface on which it is

impossible to define an orientation.

First,

the newness of the methods used in this new field gave no way to mathematicians

to present their results in the traditional deductive form of elementary

geometry. Instead, pioneers like Poincaré were forced to base themselves

largely on geometric intuition. Even today (Courant and Robbins' book was from

1941) a scholar of topology would find that insisting too much on the formal

rigors of exposition would lead to easily losing sight of the essential

geometric content of a quantity of formal particulars.

The

key word is geometrical intuition. Obviously mathematicians have in the course

of years attempted to bring Topology into the realm of more rigorous

mathematics, but that aspect of intuition remains. It is exactly these two

aspects, that of deformations that preserve some properties of the geometric

shape, and that of intuition, that have played a deep role in the idea of space

and shape, from the 19th Century right up to present day. Several Topological

ideas were to be understood by artists and architects through the course

of the decades, first by the artists

and then much later by architects.

These

shapes could not fail to interest architects, even if it would take a few

years; we had to wait for the widespread use of computer graphics, which allow

us to visualise the mathematical objects we're talking about and which support

our intuition that otherwise, for non-mathematicians, has trouble manipulating

them.

This

is what Alicia Imperiale writes in the chapter Topological Surfaces:[4]

"Architects Ben van Berkel and Caroline Bos of UN Studio discuss

the impact on architecture of new scientific discoveries (where 'new' should be

considered with a certain indulgence!). Scientific discoveries have radically

changed the definition of the term `Space', attributing a topological form to

it. Instead of a static model of constituent elements, space is perceived as

something malleable, changeable, and its organisation, its division, its

appropriation becomes elastic."

Here

is the role of topology as seen by a architect: "Topology is the study of

the behaviour of a structure of surfaces that undergo deformation. The surface

records the changes of the differential space-time shifts in a continuous

deformation. This brings further potentialities for architectural deformation.

The continuous deformation of a surface can lead to the intersection of external and internal planes in a continuous morphological change, just as in the Moebius Strip. Architects use this topological form in building design by inserting differential fields of space and time into an otherwise static structure."

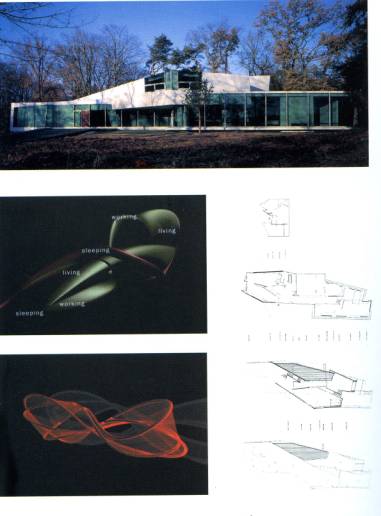

Fig.

3 Moebius House by ©

Ben van Berkel (UN Studio/van Berkel & Bos), 1993-97.

Naturally,

some words and ideas are also deformed when passing from a strictly scientific

plane to an artistic and architectural one, seen from a different point of

view. But this is not in fact a problem and needn't be a criticism. It is the

ideas that circulate freely, and everyone interprets them in their own way,

reaping the essence from them, as does Topology. Computer graphics play an

indispensable role in all this, allowing us to insert that variable of time

deformation that would otherwise be not only unmanageable but unthinkable too.

On

the topic of the Moebius Strip, Imperiale continues: "Van Berkel's house,

inspired by the Moebius Strip (Moebius House) is conceived as a

programmatically continuous structure, that encompasses the continuous mutation

of pairs of sliding dialectics that flow one into the other, from inside to

outside, from work activities to those of leisure, from load-bearing structure

to non-load-bearing structure."

In

fact, the Klein Bottle, writes Van Berkel, "can be translated into a

channeling system that incorporates all the elements it encounters and makes

them precipitate into a new type of internally connected integral

organisation." Note the words "integral" and "internally

connected" have a precise meaning in mathematics. But this is not a

problem here because the diagrams of these topological surfaces are not used in

architecture in a rigorously math-ematical manner but rather constitute

abstract diagrams, three-dimensional models that allow architects to

incorporate differentiated ideas of space and time into architecture."

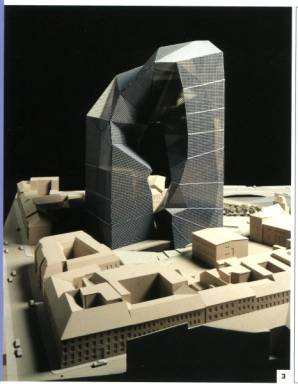

In the same time Peiter Einsenman was designing the "Max Reinhardt Haus" in Berlin. [5] "The building with arches _ made of intersecting and overlapping shapes is a unified structure that separates, gets compressed and then transformed to reconvene in a horizontal plane at the attic level. The origin of the shape is the Moebius ribbon, a three-dimensional geometrical shape featuring only one endless surface subject to three iterative operations.

Fig.

4 Eisenman Architects ©, Max Reinhardt

Haus,1992.

In

the first, the planes are generated by the extension of the vectors and the

triangulation of the surfaces. The second operation turns around the ribbon,

undertaking an operation similar to that of the first phase and therefore

places the surfaces on the initial shape, thereby creating a phantom shape. The

third phase applies an element from Berlin's history to this very shape,

enveloping wide public spaces......As the Moebius ribbon folds two sides into a

unique surface, folding it upon itself, the Max Reinhardt Haus denies the

traditional dialectic between inside and outside, confounding the distinction

between public and private."

As we mentioned, architects have, albeit a

little belatedly, learned of scientific discoveries in the field of Topology. Besides

starting to plan and build, they have started to reflect.

In

1999 in his doctoral thesis Architettura

e Topologia: per una teoria spaziale della architettura (Architecture and

Topology: Through a Spatial Theory Of Architecture) Giuseppa Di Cristina

writes: "The final conquest of architecture is space: this is generated

through a sort of positional logic of the elements, i.e. through an arrangement

that generates spatial relations; the formal value is thus substituted by the

spatial value in the configuration: what is important is not so much the aspect

of the exterior form as its spatial quality and therefore topological geometry

of non-rigid figures with no `measurements'. This is not something purely

abstract that comes before architecture, but rather the tracks left by that

modality of action in the spatial concretisation of architecture."

A volume of articles was published in 2001 on the theme "Architecture and Science" [6]. In the preface The Topological Tendency in Architecture by Di Cristina, it is explained that “The articles here bear witness to the interweaving of this architectural neo-avant-garde with scientific mathematical thought, in particular topological thought: although no proper theory of topological architecture has yet been formulated, one could nevertheless speak of a topological tendency in architects at both theoretical and operative levels. [...] In particular developments in modern geometry or mathematics, perceptual psychology and computer graphics have influenced the present renewal of architecture and the evolution of architectural thought. What most interests architects who theorise about the logic of curvilinearity and pliancy is the meaning of `event', `evolution' and `process', that is, of the dynamism that is innate in the fluid and flexible configurations of what is now called `topological architecture'. Architectural topology means the dynamic variation of form facilitated by computer-based technologies, computer-assisted design and animation software. The topologising of architectural form according to dynamic and complex configurations leads architectural design to a renewed and often spectacular plasticity, in the wake of the Baroque and of organic Expressionism."

Fig. 5

Stephen Perrella with Rebecca Carpenter©, The Moebius House Study,

1997-98

Here is what

Stephen Perrella means by "architectural topology":

"Architectural topology is the mutation of form, structure, context and

programme into interwoven patterns and complex dynamics. Over the past several

years, a design sensibility has unfolded whereby architectural surfaces and the

topologising of form are systematically explored and in folded into various

architectural programmes. Influences by the inherent temporalities of animation

software, augmented reality, computer-aided manufacture and informatics in

general, topological `space' differs from Cartesian space in that it imbricates

temporal events within form. Space then, is no longer a vacuum within which

subjects and objects are contained, space is instead transformed into an

interconnected, dense web of particularities and singularities better

understood as `substance' or `filled space'. This nexus also entails more

specifically the pervasive deployment of teletechnology within praxis, leading

to a usurping of the real (material) and an unintentional dependency on

simulation." Ideas on geometry, Topology, computer graphics and space-time

come together in these observations. The cultural links have, in the course of

the years, worked: new words, new meanings, new associations.

A short Conclusion

I

have sought to talk of several important moments that have led to a mutation of

our understanding of perception of space, seeking to gather not only the

technical and formal aspects that are also essential in mathematics, but also

the cultural aspect, by talking of the idea of space in relation to some

aspects of contemporary architecture. I would like to recall only two words

that are of great importance: fantasy and liberty. It is perhaps these two

magical words that have allowed contemporary architecture to greatly enrich

design heritage. Fantasy and liberty that come from the coming together over

the course of years of many elements: computer logic, new geometries, Topology

and computer graphics. For, even if very few people realise it, mathematics is,

or can be, the kingdom of liberty and fantasy.

Without

all this, the planning of the Museum of The Hellenic World would have been

unthinkable. A culture started in that place thousands of years ago and that

would be celebrated in that same place with a construction highly symbolic of

the history of the culture of the Mediterranean.

References

[1]

K. W. Forster, ed., Metamorph:Focus,

catalogue, La Biennale di Venezia, Marsilio ed. , 2004, p. 31-43.

[2]

A. Imperiale, New Bidimensionality,

Birkhauser, Basel (2001)

[3]

M. Emmer, Mathland: from Flatland to

Hypersurfaces, Birkhauser, Boston (2004) (It. ed., Testo ed Immagine, ed.,

Torino, 2003).

[4] A. Imperiale, in [2] .

[5]

Eisenman Architects, Max Reinhardt Haus,

in Metamorph: Trajectories,

catalogue, La Biennale di Venezia, Marsilio ed. ,2004, p. 252.

[6]

Di Cristina, G., ed., Architecture and

Science,Wiley-Academy, Chichester (2001)

On the links between mathematics

and culture:

M.

Emmer, ed., Matematica e Cultura2000,

Springer verlag Italia, Milano, (2000); English edition, Springer verlag,

Berlin (2004)

M.

Emmer, ed., Matematica e Cultura2001,

Springer verlag Italia, Milano (2001)

M.

Emmer, ed., Matematica e Cultura 2002,

Springerverlag Italia, Milano (2002)

M.

Emmer, ed., Matematica e Cultura2003,

with musical CD, Springer verlag Italia, Milano (2003); English edition in

preparation.

M.

Emmer, M. Manaresi, eds., Matematica,arte,

tecnologia, cinema, Springer verlag Italia, Milano (2002);150 pages are

dedicated to cinema fiction and mathematics, Springer verlag, Berlin (2004)

M.

Emmer, ed., Mathematics and Culture 2:

Creativity and Visual perfection, Springer verlag, to appear 2004.

M.

Emmer, ed., Matematica e Cultura 2004,

Springer verlag Italia, Milano (2004); English edition in preparation.

M.

Emmer, ed., Matematica e Cultura2005,

Springer verlag Italia, Milano, in preparation.

Web

"Matematica e Cultura": http://www.mat.uniroma1.it/venezia2004 (the

date in October changes eachyear)

M.

Kline, Mathematics in Western Culture,

OxfordUniversity Press, New York (1953)

On the links between mathematics

andachitecture:

M.

Emmer, Mathland, from Flatland t

oHypersurfaces, Birkhauser, Boston (2004)

Topologia e Morfogenesi, ED La Biennale, Venezia(1978)

Ben

van Berkel, Mobile Forces / Mobile Krafte,

Ernst &Sohn Verlag, Berlin (1994)

John

Beckmann, ed., The Virtual

Dimension:Architecture, Representation, and Crash Culture, Princeton

Architectural Press, New York (1998)

G. Di Cristina, ed., Architecture and Science, Wiley Academy, Chichester (2001)

Illustrations:

Fig. 1 Anamorphosis Architects, Athens, Greece, Project for the museum of the Hellenic world

(2002), © Anamorphosis Architects

Fig.

2 Frank O. Ghery Project for the new Guggenheim museum inManhattan. C Courtesy of © Keith Mendenhall for the Gehry Partners

Studio.

Fig.

3 Moebius

House by © Ben van Berkel (UN Studio/van Berkel & Bos), 1993-97.

Fig.

4 Eisenman Architects ©, Max Reinhardt Haus,1992.

Fig. 5 Stephen Perrella with Rebecca Carpenter ©, The Moebius House Study, 1997-98