BUILDING [IN] FRAGMENTS

A Case Study on

Karm El-Zeitoun

Sandra Bsat, BArch.

Department of Architecture &

Design, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon.

e-mail: sandra@cyberia.net.lb

Abstract

Classifying structures embodied in physical space and social practices have become a sub-level of understanding whereby questions like "what does it mean to build this wall in such a way and not differently? Whom does it address? And how is it functional through shaping and reflecting social practices?" Utilizing and manipulating urban and architectural semiology becomes a tool of discourse whereby meaning and form start to constitute and mutually define each other. The interest lies, however, in the mechanisms of differentiation and othering that operate as indicators of class structures and are perpetuated through the production of meanings at the social and cultural levels. The attempt of this research is to highlight and bring to the surface such mechanisms through Karm El-Zeitoun, which is the site of investigation. Karm El-Zeitoun is produced through internal social practices that are produced by the other as their other. The challenge of Karm El-Zeitoun is the fact that mechanisms of "differentiation" and "othering" function at a very specific and integral level internal to it; whereby they become visible through its production. Consequently, classifying structures become operative at the level of the city as much as they become operative at the level of Karm El-Zeitoun as an entity by itself. In this paper, I will be dealing with the notion of fragmentation through social/physical structures in Karm El-Zeitoun and their inter-relational dependence as one cohesive and unified network whereby the notion of dismemberment starts to entail more than dismantling objects but rather transcends that to become a tool of discourse. The aim of this research is to methodologically deal with the complexities of such contexts as Karm El-Zeitoun and see how we, as architects from without, can intervene within such site- specific complexities.

Introduction

Architecture has the power to talk, defy, embrace, segregate and alienate. Physical space, through projecting meanings embodied and produced by social practices and structures, which dialectically produce it, creates a lexicon of relations and conditions that become political tools of power. Physical space becomes a tool of negotiation among social classes where desired positions within class structures are transposed into desired positions within physical space. The mechanisms, operative through fragmentation at the architectural and urban/social levels, produce complex networks for our intervention as architects. Issues of differentiation, classification and alienation are integral to the course of this research through, what I will have the liberty to call an urban phenomenon, Karm El-Zeitoun. The question remains: How can we build [IN] fragments?

Fragments Defined

My interest in Karm El-Zeitoun lies in the complexities of relations, physical and social, it offers. The attempt is to fragment the place into a set of relationships and understandings, like rules to be reinterpreted later on in design interventions through juxtaposition, transformation and transcription. "If space is a product, our knowledge of it must be expected to reproduce and expound the process of production. The 'object' of interest must be expected to shift from things in space to the actual production of space."[1]

Fragment 1

Overview

![]()

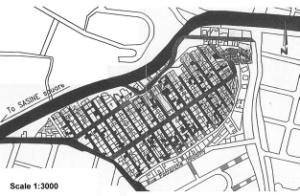

Karm El-Zeitoun[2]

was given to the Armenian fugitives from the Turkish genocide in the 1920's as

a planned olive grove, with urban considerations (see Figure 1). It sits on the

very steep hill of Achrafieh, on the eastern edge of municipal Beirut.

It is bordered from the east, which is its lowest edge, by the river of Beirut,

from the north by Ararat Street, which leads up to Sassine square and

which is considered a main axis in Achrafieh, from the west and the

south by Cheikh El-Ghabi Street and Patriarch Douaihy Street

respectively, which separate Karm El-Zeitoun from what the locals denote as the

"classy sector" where the rich and exclusive live. It happened that I

experienced the place before seeing its plan, and so, as you can imagine, it

came as a shock to see that a place so complex, multifarious and intricate

would have a spatial organization that resembles that of an American suburbia;

so organized and structured. The plan of Karm El-Zeitoun is that of a grid

sliced by two main axes from which minor parallel alleys emanate till they

reach the steep edges where they transform into stairs that lead down to the

lower levels. Looked at today, and because of its overpopulation and mechanisms

of construction, Karm El-Zeitoun seems like a place on the tip of explosion. It

appears that the planning scheme which was supposed to play an urban organizing

role was bluntly overwritten, denied and transcended; however, the matter of

fact is that the grid reappears again; it forms defining edges whereby the

overwriting and transgression starts to operate inside the limits of the block

where organizing structures fail to exist as part of the planning scheme.

Architecture, inside the limits of the block, falls into a game of

disfiguration; it is no longer conceived and dealt with as a totality but as

elements to be manipulated, cut, pasted, replicated, connected and

disconnected. Though it might seem to the first-time observer (me, as architect[3])

that Karm El-Zeitoun is a site of architectural horror, of chaos and anarchy,

it embodies a very intricate social system and a physical aspect underlined by

the logic of need through which the issue of fortification starts to manifest

itself.

Karm El-Zeitoun[2]

was given to the Armenian fugitives from the Turkish genocide in the 1920's as

a planned olive grove, with urban considerations (see Figure 1). It sits on the

very steep hill of Achrafieh, on the eastern edge of municipal Beirut.

It is bordered from the east, which is its lowest edge, by the river of Beirut,

from the north by Ararat Street, which leads up to Sassine square and

which is considered a main axis in Achrafieh, from the west and the

south by Cheikh El-Ghabi Street and Patriarch Douaihy Street

respectively, which separate Karm El-Zeitoun from what the locals denote as the

"classy sector" where the rich and exclusive live. It happened that I

experienced the place before seeing its plan, and so, as you can imagine, it

came as a shock to see that a place so complex, multifarious and intricate

would have a spatial organization that resembles that of an American suburbia;

so organized and structured. The plan of Karm El-Zeitoun is that of a grid

sliced by two main axes from which minor parallel alleys emanate till they

reach the steep edges where they transform into stairs that lead down to the

lower levels. Looked at today, and because of its overpopulation and mechanisms

of construction, Karm El-Zeitoun seems like a place on the tip of explosion. It

appears that the planning scheme which was supposed to play an urban organizing

role was bluntly overwritten, denied and transcended; however, the matter of

fact is that the grid reappears again; it forms defining edges whereby the

overwriting and transgression starts to operate inside the limits of the block

where organizing structures fail to exist as part of the planning scheme.

Architecture, inside the limits of the block, falls into a game of

disfiguration; it is no longer conceived and dealt with as a totality but as

elements to be manipulated, cut, pasted, replicated, connected and

disconnected. Though it might seem to the first-time observer (me, as architect[3])

that Karm El-Zeitoun is a site of architectural horror, of chaos and anarchy,

it embodies a very intricate social system and a physical aspect underlined by

the logic of need through which the issue of fortification starts to manifest

itself.

Fragment 2

From the Margin to the Center to the Margin

Karm El-Zeitoun, when it was given to the Armenians as a refuge was conceived of as a field at the edge of the city of Beirut; at the margin. As marginalized as its inhabitants, Karm El-Zeitoun embraced its own community and provided a site for the permanence and proliferation of a cultural and social heritage. During the Lebanese civil war, Beirut was divided in two, by the Green Line: East Beirut and West Beirut. Each side started to expand from the center to the periphery, to accommodate refugees, thus moving away from the critical central zone. Consequently, areas that once were at the edge of Beirut became central to their own portion of the separated city. After the war, when Beirut was unified once again, areas like Karm El-Zeitoun found themselves in the heart of the city surrounded by populated and well-established areas from all sides. However, this integration did not last long, for a new kind of marginalization began to formulate. The post-war period witnessed the emergence of new class structures with the return of rich Lebanese migrants and the nouveau-riche; a fact that created new boundaries in the social fabric of the city. These boundaries manifested themselves physically in the space of the city thus emphasizing class differences through the appropriation and production of a localized web of sites in different parts of Beirut led by the star-site, the Beirut Central District. Consequently, Karm El-Zeitoun was again located within an edge condition; an edge condition that is not defined by physical boundaries which can be easily transgressed, but by a complex network of social, cultural, economical and political boundaries that are so tightly structured that they become very difficult to transcend. [To rent a house in Karm El-Zeitoun it costs an average of about $150/month while in places like Cap sur Ville, an apartment's rent is about $2000, excluding maintenance and service expenses].

Fragment 3

Aesthetics of Conformity

where Karm El-Zeitoun

ends & the facade begins![]()

A very significant phenomenon that would

capture the imagination of any observer in Karm El-Zeitoun is the attempt to

aesthetisize the river front of this "ugly and chaotic" area. Ever

since the renovation and unconditional intervention of Solidere in the BCD

(Beirut Central District), it has become the reference of what is to be

considered "beautiful" in the city; spick and span, polished,

well-organized, and so on. It was a dream come true for a lot of people

in Lebanon, whether they were in power or not, but since such a drastic and

gentrifying project was not possible to implement in all parts of the city, new

techniques were devised. Instead of "cleaning up the mess" it was

more feasible to "shove the dust under the carpet." In Karm

El-Zeitoun for example, the Lebanese government commissioned a French

organization "Help Lebanon", in the summer of 2002, to paint the

river front of Karm El-Zeitoun with nice colorful murals of up-scaled clock

towers (see Figure 2), trees, clouds and a blue sky frozen in time all year

long. The project entails dressing up Karm El-Zeitoun in colorful garments

hiding the inadequacies that the place projects on the rest of the city thus

disillusioning the foreign full-of-dollars investment-hunting eye. The

government, consequently, found that the best way to deal with

"problems" like Karm El-Zeitoun is to drop a curtain on it and

pretend it does not exist. The extent by which the front of Karm El-Zeitoun is

conceived as a façade to the city is extremely visible by the marks and edges

of paint, detaching the façade from the rest of Karm El-Zeitoun like a screen.

Fragment 4

Stacking / Layering: A New Condition

![]()

The Armenians exploited their newly granted land and began to

construct their dwellings there within the limitations of the planning scheme.

During the Lebanese civil war, different groups from different parts of Lebanon

came to Karm El-Zeitoun, partly as a refuge and partly to exploit the

employment opportunities which were lacking in their cities or villages and

which the capital was able to provide. The main advantage they saw in Karm

El-Zeitoun was the fact that housing there was cheap. Both parties, the

Armenians and the newcomers, took advantage of each other; the Armenians made

money by renting their rooms or houses, and the newcomers were happy to find

accommodation at such low prices. So, the number of inhabitants increased

drastically and the existent houses were no longer sufficient; new solutions

had to be devised and implemented. The fact that Karm El-Zeitoun is physically

bounded from four sides made a horizontal extension impossible to attain;

therefore, the expansion had to happen vertically. One on top of the other,

people started to build their dwellings from other dwellings, where the roof of

one became the porch of another, windows became doors and doors became walls.

Karm El-Zeitoun is involved in a constant additive process taking full

advantage of its physical givens; nevertheless, retaining the stepped quality

of the hill thus providing sunlight and air circulation to the insides of the

place (see Figure 3).

The Armenians exploited their newly granted land and began to

construct their dwellings there within the limitations of the planning scheme.

During the Lebanese civil war, different groups from different parts of Lebanon

came to Karm El-Zeitoun, partly as a refuge and partly to exploit the

employment opportunities which were lacking in their cities or villages and

which the capital was able to provide. The main advantage they saw in Karm

El-Zeitoun was the fact that housing there was cheap. Both parties, the

Armenians and the newcomers, took advantage of each other; the Armenians made

money by renting their rooms or houses, and the newcomers were happy to find

accommodation at such low prices. So, the number of inhabitants increased

drastically and the existent houses were no longer sufficient; new solutions

had to be devised and implemented. The fact that Karm El-Zeitoun is physically

bounded from four sides made a horizontal extension impossible to attain;

therefore, the expansion had to happen vertically. One on top of the other,

people started to build their dwellings from other dwellings, where the roof of

one became the porch of another, windows became doors and doors became walls.

Karm El-Zeitoun is involved in a constant additive process taking full

advantage of its physical givens; nevertheless, retaining the stepped quality

of the hill thus providing sunlight and air circulation to the insides of the

place (see Figure 3).

Fragment 5

Street / Stair Redefined

One of the most significant features of Karm El-Zeitoun is the combination of a street / stair network resulting from the overlapping of a grid and a steep topography; whereby the parallel character of the streets transforms itself into crooked stairs to accommodate for the extreme change in levels with very defined edges. The gridded street network provides a sort of an edge that defines the building blocks adjoining it; whereas, the stairs are defined by the blocks that surround them. Sometimes the stairs penetrate the houses, go over them, above and in between; their landings become porches and their steps become spaces for socializing, playing cards, drying laundry, cooking smelly food like frying fish or barbequing, sunbathing on a good day, and so on. The stairs gain new meanings and start to function differently; they no longer are mere access ways but spaces with an acquired social baggage of meanings. The streets, similarly, become impregnated social spaces but that function slightly differently. The main difference between the social context of the street and the stair is the fact that since the street lies on a relatively horizontal plane, it provides a better setting than the stair for commercial arteries to emerge, and, consequently, the form of social relationships that materializes is more intermixed, variable and juxtaposed rather than domesticated, private and limited as is the case with the stairs.

Fragment 6

Ethnic / Religious Composition

The first residents of Karm El-Zeitoun were Christian Orthodox Armenians. Later, other Lebanese Christians moved in, in addition to a group of Muslim Shiites from South Lebanon. The new community formed groups of different religious and ethnic backgrounds organized in clusters in Karm El-Zeitoun defining new boundaries of social interaction and power structures. In the last five years or so, however, new residents moved in, constituted of foreign labor forces i.e. Sri Lankan and Ethiopian domestic workers (mainly females), in addition to Syrian and Egyptian laborers (mainly males) who live communally in shared apartments to minimize their living expenses and to sustain a homey environment in a foreign aggressive context. Their presence has ever since instigated friction among the residents whereby coalitions started to form according to different criteria of "othering" depending on what is at stake. Fights and harassments happen constantly in Karm El-Zeitoun between Muslims and Christians, locals and immigrant workers, and so on creating a milieu of aggression and tension among the inhabitants.

Fragment 7

The Armenian Orthodox Church: "Othering" by Self-definition

Despite the juxtaposing and overlaying that becomes a physical characteristic of Karm El-Zeitoun, one object stands out giving way to a new understanding of the social / spatial dialectics already present. The Armenian Orthodox Church presents itself as an object in space so well defined that it emphasizes the notions of juxtaposition and layering differentiating the rest of Karm El-Zeitoun from itself. The church is the only religious institution in Karm El-Zeitoun, despite the multitude of ethnicities and religious backgrounds present, that functions as an icon and signifier of a power structure that is asserted through its presence. It is so well taken care of, newly painted and clean, independent of the surrounding fabric whereby an empty space is created around it. Aside from its religious connotations, the church becomes a tool for manipulating the power structure in Karm El-Zeitoun; it identifies a group of people, the Armenians, and presents them with the right of territoriality and dominance. The function of the church as an object of power becomes more and more crucial with every newcomer to Karm El-Zeitoun; it immediately puts everyone, non-Armenian Orthodox, in opposition as the "other" to itself, claiming the Armenian body as the "identity" of the place, a localized physical object.

Fragment 8

Fixed vs. Mobile Tools of Power: Chair vs. Wall

![]()

In an attempt to understand the physicality of Karm El-Zeitoun as a

potential tool of power, two forms of physical elements start to manifest

themselves: the mobile and the stationary. The

chair (see Figure 4) is present in Karm El-Zeitoun extensively in the public

space, creating a pattern of physical objects which are mobile, mutable and

extendable. The chair becomes a tool of power, a social practice, projecting

gazes, monitoring social practices, extending the boundaries of the private space

into the "public" space. The chair also plays a socializing role

whereby shopkeepers sit awaiting potential customers. It becomes a trigger of

conversations, chats and debates with other shopkeepers and/ or passers-by. The

chair plays a major role in animating the place, defining territoriality and,

consequently, privatizing the street. The chair becomes a tool of power; of

surveillance and control, but, at the same time, it provides a defence system

that endows Karm El-Zeitoun with security and a sense of protection. Fixed

tools of power, on the other hand, are mainly the consequence of Karm

El-Zeitoun's spatial organization and topography. The place provides visibility

patterns that induce positions of privilege, disadvantage or parity. One is

either above, under or at the same level as another. But each position takes

different forms of course and that is mainly because of the richness and

complexity of spatial relationships the place provides. The significance here

lies in the fact that the gaze is not intentional and conscious but is actually

influenced, manipulated and operated by its spatial context. In Karm

El-Zeitoun, instead of forcing the gaze into the guts of houses and private

sectors, one forces oneself out. Again while I was conducting my fieldwork

there, I had to employ an effort not to look inside houses where people were

having their lunch, chatting, watching TV, etc. in their pyjamas, linen and

slippers, sometimes half naked. As Beatriz Colomina put it, "architecture,

therefore, is not simply a platform that accommodates the viewing subject. It

is a viewing mechanism that produces the subject. It precedes and frames its

occupant".[4]

My discomfort in Karm El-Zeitoun, however, was not the consequence of its

spatial organization and the relationships it creates, but mainly because of

the social practices associated with my breeding and social education where the

public and the private are very well defined and where it becomes taboo to peep

into other people's private spaces. The reason why I relate that to social

practices is the fact that while I was feeling extremely discomforted, and a

bit ashamed, for having to gaze into the insides of houses, the inhabitants,

though they clearly were able to spot me, were indifferent to my presence; in

other words, they were used to it; it was an inherent practice in their social

life and existence.

In an attempt to understand the physicality of Karm El-Zeitoun as a

potential tool of power, two forms of physical elements start to manifest

themselves: the mobile and the stationary. The

chair (see Figure 4) is present in Karm El-Zeitoun extensively in the public

space, creating a pattern of physical objects which are mobile, mutable and

extendable. The chair becomes a tool of power, a social practice, projecting

gazes, monitoring social practices, extending the boundaries of the private space

into the "public" space. The chair also plays a socializing role

whereby shopkeepers sit awaiting potential customers. It becomes a trigger of

conversations, chats and debates with other shopkeepers and/ or passers-by. The

chair plays a major role in animating the place, defining territoriality and,

consequently, privatizing the street. The chair becomes a tool of power; of

surveillance and control, but, at the same time, it provides a defence system

that endows Karm El-Zeitoun with security and a sense of protection. Fixed

tools of power, on the other hand, are mainly the consequence of Karm

El-Zeitoun's spatial organization and topography. The place provides visibility

patterns that induce positions of privilege, disadvantage or parity. One is

either above, under or at the same level as another. But each position takes

different forms of course and that is mainly because of the richness and

complexity of spatial relationships the place provides. The significance here

lies in the fact that the gaze is not intentional and conscious but is actually

influenced, manipulated and operated by its spatial context. In Karm

El-Zeitoun, instead of forcing the gaze into the guts of houses and private

sectors, one forces oneself out. Again while I was conducting my fieldwork

there, I had to employ an effort not to look inside houses where people were

having their lunch, chatting, watching TV, etc. in their pyjamas, linen and

slippers, sometimes half naked. As Beatriz Colomina put it, "architecture,

therefore, is not simply a platform that accommodates the viewing subject. It

is a viewing mechanism that produces the subject. It precedes and frames its

occupant".[4]

My discomfort in Karm El-Zeitoun, however, was not the consequence of its

spatial organization and the relationships it creates, but mainly because of

the social practices associated with my breeding and social education where the

public and the private are very well defined and where it becomes taboo to peep

into other people's private spaces. The reason why I relate that to social

practices is the fact that while I was feeling extremely discomforted, and a

bit ashamed, for having to gaze into the insides of houses, the inhabitants,

though they clearly were able to spot me, were indifferent to my presence; in

other words, they were used to it; it was an inherent practice in their social

life and existence.

Fragment 9

The Roof: A Space of Deviance

The additive process of construction that characterizes Karm El-Zeitoun has led to a very intricate interconnected roof system which diminishes in-between spaces if not completely eliminates them. It creates a platform of juxtaposed planes, stairs, thresholds, gaps, intrusions and extrusions that form a continuous fabric projecting, transcribing and transforming ground 0. The roof becomes an indicator of transforming typologies and changing relations creating new conditions in space. It becomes an apparatus for transgressing boundaries whereby acts of deviance begin to manifest themselves. Mireille, a student, moved into Karm El-Zeitoun with two of her friends because of its proximity to their university and its very low renting rates. They have to work at night and come back at one in the morning if not later. They are perceived and surveyed by their neighbours every time they leave their apartment and every time they come back. For girls to live alone and to go out and come back at such late hours and whenever their wanted is a situation foreign to the inhabitants of Karm El-Zeitoun; it is a state of deviance. However, this deviance manifests itself through physical space by the appropriation of the rooftops as spaces of resistance to overpower and manipulate a social pressure that does not accept an "other" lifestyle. Mireille and her friends, being aware of the intricate network the rooftops provide, exploit it to exit and access Karm El-Zeitoun at "inappropriate" times; they go up to the roof of their building and move their way out by transgressing interconnected roofs till they reach the main street where they go down the stairs of an adjacent building onto the street, and consequently, to their chosen destination in the city. Another event, that actually has transformed the rooftops of Karm El-Zeitoun into a legend, is the story of Garo. Garo was an outlaw who lived in Karm El-Zeitoun and who was chased by the police for seven years. During those seven years, he never left Karm El-Zeitoun but used it as his hideout. Through local social support and a rooftop network that functioned continually as a means of escape, he was able to defer the police from capturing him several times. Consequently, the rooftops of Karm El-Zeitoun, interconnected and continuous, cease to be spaces of excess, where water containers, antennas and old useless objects are stored or disposed of, and become spaces with social significance affecting directly the lives of the inhabitants. They become hideouts, means of escape and transgression, projecting the non-possibilities of the streets and alleys of Karm El-Zeitoun to another level creating a new layer of a social / physical interdependence.

Finally, as a conclusion, the main question remains: how feasible is our process of design, which entails the production of meaning through representation, within a context like Karm El-Zeitoun where meaning is produced and reproduced through lived space? Can these fragments act as an interface between a site and an architectural or urban intervention, and in what ways? For people who deal with the physical, with objects, it is important to be able to inject oneself into a process that would allow for a shift from dealing with a context as objects in space to an actual production of space. This fact would allow for architecture, as a discipline, to transgress the boundary of mere formalism and attain the complexity of a social/spatial dialectics; thus becoming more of a social art rather than a set of mere fashionable attempts.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my utmost gratitude and appreciation to the people who taught me how to learn, my advisors Chairperson Prof. Howayda Al-Harithy, Prof. Rana Haddad and Prof. Marwan Ghandour.

References

[1] Colomina, B., "The Split Wall: Domestic Voyeurism" in Sexuality and Space, Princeton Architectural Press, NY (1992)

[2] Lefebvre, H., The Production of Space, Blackwell Publishers Inc., UK (1998)