The

generative approach in the Botta’s San Carlino

Prof.

Nicoletta Sala

Accademia di

Architettura, Università della Svizzera italiana

Mendrisio, Switzerland

e-mail: nsala@arch.unisi.ch

Prof. Arch.

Gabriele Cappellato

Accademia di

Architettura, Università della Svizzera italiana

Mendrisio, Switzerland

e-mail: gcappellato@arch.unisi.ch

Abstract

The

aim of this paper is to describe the origin of the wooden model of the San Carlino (1999) located in Lugano, and realized by the Swiss

architect Mario Botta.

To

introduce it, we will describe the Baroque style, the importance of the

mathematics in the Baroque

architecture, and the characteristics

of the Borromini’s church named San Carlo

alle Quattro Fontane (1638-1641, Rome). After, we will explain the Botta’s

wooden model conceived to commemorate Francesco Borromini (1599-1667). It is an example of a new kind of

monument. The starting point for our

investigation has been to consider the Baroque characteristics of the Borromini’s project and the generative

approach that Mario Botta has used to conceive and to plan the wooden model of

the San Carlino. For example:

·

the metaphors,

·

the dialog of the context,

·

the territory of the memory,

·

the

fragment to describe an architectural work.

Mario

Botta using this approach in his San

Carlino has obtained a symbolic and unexpected home coming of Francesco Borromini in his territory.

1.

Introduction

The

Baroque (1600-1750) was born in Italy, and adopted in Germany, Netherlands,

France, and Spain [Schneider, 2001]. The term “Baroque” was probably derived

from the Italian word “barocco”, which was a word used by the philosophers

during the Middle Ages to describe a hindrance in a schematic logic. After,

this have been used to describe any

contorted process of thought or complex idea. Another possible meaning derives

by the Spanish “barrueco”, Portuguese form “barroco”, used to describe an

imperfect or irregular shaped pearl. This word has survived in the jeweller’s

term “Baroque pearl”.

Baroque

was also associated with the Catholic art, but during the centuries it

progressed and diffused its style into the Protestant countries. In fact, it is

a style that expressed power and rigour, “the style of absolutism”. Baroque

favoured higher volumes, exaggerates decorations, and colossal sculptures

[Stella, 1987; Hersey, 1999; Careri, 2003].

The

Baroque suggested movement in static works of art, and it influenced

important challenges in architecture

[Harbison, 2000]. Baroque architecture was based on the mathematics [Hersey,

2000]. In the age of the Baroque, the architects and the patrons thought of the

buildings as “studies in practical mathematics” (this is a phrase of the religious

Virgilio Spada (1596-1662), that has realized the plan of the Chapel Spada)

[Portoghesi, 1970; Magnuson, 1986; Hersey, 2000].

Guarino

Guarini (1624-1683), in his posthumous book entitled Architettura Civile (1737), wrote in its preface how “excellent a geometer Father Guarini was, how versed

and profound in all part of mathematics, and especially the part that

constitutes civil architecture” (“eccellente geometra fosse il Padre Guarini, e

quanto versato e profondo in tutte le parti della Matematica e in questa

spezialmente dell’Architettura Civile”) [Guarini, 1737].

George

Hersey, professor of the history of the

art, affirms: “I said that in the age of the Baroque the people believed in

hierarchies of number and form but some numbers were reliable and others were

unreliable. For example Guarino Guarini affirmed: “Some proportions are

effable, and can manifest themselves by [rational] numbers, for example the

proportion of an inch to a foot, 1:12. But other proportions are ineffable and

cannot be expressed in [rational] numbers, but are called irrationals, for

example the side of a square with its diagonal, as proved by Euclid Book 12,

Proportion 4[1]” [Hersey,

2000; p. 7].

Baroque

architecture can be considered as a continuation of High Renaissance architecture,

because it used the symmetry, and a kind of simple geometry combined with a

greater aesthetic sense of smoothed surfaces.

Baroque architecture also used spirals, helixes and curves (for example,

ovals, circles and ellipses) to realize smoothed shapes. Figure 1 shows an

examples of Baroque decorations [Sala and Cappellato, 2003].

Figure 1 An example of Baroque decorations

One

of the most important architectural projects was the rebuilding of the Basilica

of San Pietro, which involved the architects of the Roman Baroque: Carlo

Maderno (1566-1629), Francesco Borromini (1599-1667), Gian Lorenzo Bernini

(1598-1680), Carlo Fontana (1638-1714). The Baroque architecture could be

analysed using a fractal point of view. Fractal geometry is a modern discovery

of the science, that permits to describe irregular shapes. The most important

fractal property is the self-similarity. A fractal object is self – similar if

it has undergone a transformation whereby the dimensions of the structure were

all modified by the same scaling factor. The new shape may be smaller, larger,

translated, and/or rotated, but its shape remains similar [Sala and Cappellato,

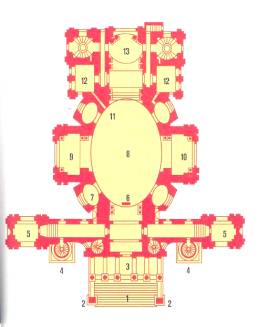

2003]. Baroque architecture is self-similar; for example the self-similarity is

present in the plans of some churches, as shown in the figure 2, which

illustrates the plan of church of Saint Karl (1715-1737, Vienna) where the oval

is repeated in three different scales.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Figure 2

The plan of the church of Saint

Karl (Vienna) shows some self-similar shape.

In

this paper we will describe an example of Borromini’s church and its wooden

model realized by the Swiss architect Mario Botta.

The

paper is organized as follow: the section 2 describes the characteristics of

the Borromini’s church San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane. In the section 3 we

present the wooden model of this church realized by Mario Botta. The section 4 contains the conclusions and

in the section 5 there are our references.

2. The church of San Carlo

alle Quattro Fontane (Rome)

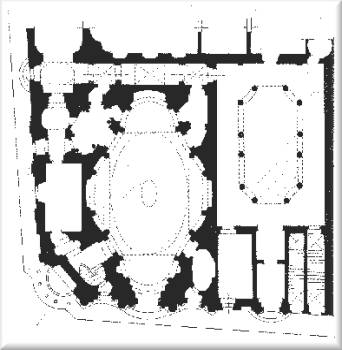

The

church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane (also named San Carlino) was realized

in Rome by Francesco Borromini. The project begun in 1638. The main facade,

with three bays (shown in figure 3), is located in a narrow road, and the

second facade, a little bay at the corner with its own tower, were designed

after the interior was completed.

This

small Baroque church is a part of a monastery, and it used the gigantic order

enclosing a small order [Blunt and Erwee, 2003]. Observing the Borromini’s

preliminary drawings (shown in figure 4) we can note that the church interior

is organized upon two equilateral triangles sharing a common side with two

circles inscribed within them. The two circles are combined to form an oval,

describing the area of the dome [Hatch, 2002].

In

the church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, the longitudinal chapels are

defined to form an oval, the oval plan is often met in the Baroque

architecture, while the lateral chapels are marked out by the shared corners of

the triangle. Borromini used the octagons, the Greek crosses and other shapes

for the coffering of the dome of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane. The figure 5

shows the lattice used to map a detail from Borromini’s dome coffers in San

Carlo alle Fontane, and figure 6 illustrates the dome interior where the ends

of each lozenge and of each rhombus are unequal, the upper half of each octagon

is smaller than the lower half, and the top of the upright in each Greek cross

is shorter than the bottom of the lower part of the cross’ upright [Hersey, 1999].

Observing figure 5, we can see the presence of two directional compressions,

horizontal and vertical at the same time, over a (much shallower) dished plan.

Borromini probably achieved the dome interior coffers using a particular

technique. These compressions introduces a kind of self-similarity in the dome.

Figure 3 The main facade of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane (Rome)

Figure 4 San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, Rome. Detail of the plan

Figure 4

The lattice used to map a detail in the Borromini’s dome [Hersey, 1999]

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Figure 5 Dome, San

Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, Rome. The arrows connect the self-similar shape

George

Hersey affirms: “The technique involved using a single-source light to project

the shadow of a full-scale, ortholinear grid, made of ropes, onto the curved

vault surface. Then the preparatory cartoon with its corresponding grid could

be redrawn onto the vault, but obeying the projected co-ordinates that were now

properly curved - swollen and contracted – by the vault’s curved surfaces. As

the co-ordinates were curved, so then would be the figure drawings constructed

from them. I assume that Borromini used the same projection system to map out

his coffers at San Carlino. The method is described in a contemporaneous treatise.”

[Hersey, 1999, p. 53].

3. The Botta’s San Carlino (Lugano)

To celebrate the 400 years after the birth of the Swiss architect

Francesco Borromini, Mario Botta, with the collaboration of Università della Svizzera Italiana, realized

on the lake-front of Lugano the reconstruction, in real size, of the famous

church San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane built in Rome by Borromini. This wooden model is allocated on a platform situated on the lake of

Lugano.

The particularity of this masterpiece (33 meters high and 90 tons

weight) is the construction with 35000 of wood boards of cm 4.5 in thickness

with cm 1 space between the boards.

This is an audacious invention that proposes itself as architecture and

set, as sculpture and installation. This wooden model represents an act of

memory, the celebration of the birth of Francesco Borromini, using a reference

the church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, the first important work realized

by Borromini.

There some differences between the real church and its model, in fact

the real is whole, the model is in section. The church is in the urban tissue

of Rome and its model is situated on a

platform on the lake of Lugano, that is encircled by mountains; the same

mountains that Borromini observed in his one’s early youth. The model is seen devoid of its decorations, without its façade, and

without its side chapels. In this way, we can

describe the Botta’s work as a “building – representation” which permits “to

observe” the Roman church and the territory that contains it.

Botta affirms: “The project to reconstruct the San Carlino, was born in

Lugano in 1999, to celebrate the 400 years after the birth of Francesco

Borromini. The Museo Cantonale of Lugano, the Hertziana of Rome and the

Albertina of Vienna agree on the commemoration on Borromini. When the

organizers have called me to prepare an exhibition dedicated to Borromini, I

have tackled the problem about the different rules of the cities of Lugano,

Rome, and Vienna. Our unique opportunity was to consider that we

had the history, the territory where Borromini lived his infancy. In this way,

the celebrations dedicated to Borromini have been organized using different

themes for different localities: Lugano hosted the years of the Borromini’s

youth, Rome and Vienna his artistic productions”[Bellini and Minazzi, 1999;

Botta and Cappellato, 1999; Papi et al., 2002; Sala and Cappellato, 2003].

Botta

read on the Carlo Dossi book entitled: Note

Azzurre the following phrase: ”Il carattere dominante delle architetture è

dato dal contesto che colpisce l’occhio dell’artista (The dominant character of

the architectures is furnished by the context that strikes the artist’s eyes”.

Dossi’s

consideration is important: it is the context that represents the architecture

and it is not the architect’s personality, or his techniques. For example,

Dossi affirmed that the architectures of the desert are influenced by the

desert.

Mario

Botta, using the Dossi’s point of view, decided to realize a reconstruction of

a church of Borromini directly on the

lake of Lugano. In fact, the geographic configuration of the territory has not

been modified in this four centuries.

Botta

has chosen to realize the model of the church of San Carlo alle Quattro

Fontane, because this is the first Borromini’s work that has furnished

celebrity to this architect.

Botta has

conceived a provocative answer, that does not belong to the symbols but to the

imaginary. In fact, he has realized a wooden model, using a cross-section, separated by the urban context that has

influenced the real church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane. This

characteristic suggests some

reflections on Dossi’s point of view.

The

territory of the memory, used by Botta, represents the element of comparison

that the architect uses to dialog with the project. The Botta’s San Carlino,

located on the lake of Lugano, is an disquieting presence because it compares

itself with the modern town of Lugano. The “past” is compared with the

“present”, without prejudices, the melancholic shadow that reveals by the Baroque

shapes is filtered by the contemporary language [Botta, 1999].

Botta’s

San Carlino is an architectural work expressed using a fragment. The

interrupted geometry of this wooden model obliges to a subjective

interpretation [Botta, 1999].

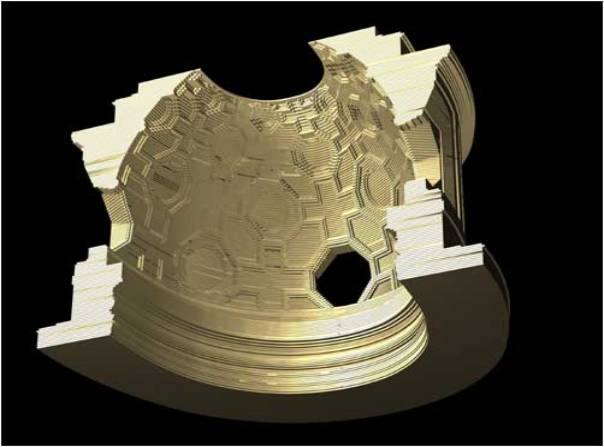

We

have studied the geometry present in

the real church and in the wooden model and we have found a kind of fractality.

The fractal geometry is present in the church of San Carlo alle Quattro

Fontane. A kind of self-similarity has been used by Borromini, and reproduced

by Botta, in the shapes for the coffering of the dome. In our interpretation,

the dome is like a fractal object, in fact it has undergone a transformation

whereby the dimensions of the structure were all modified by the same scaling

factor (see figures 5 and 8). The new shape may be smaller, larger, translated,

and/or rotated, but its shape remains similar [Sala, 2003]

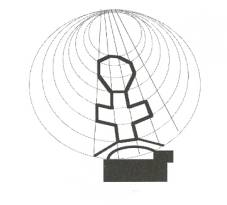

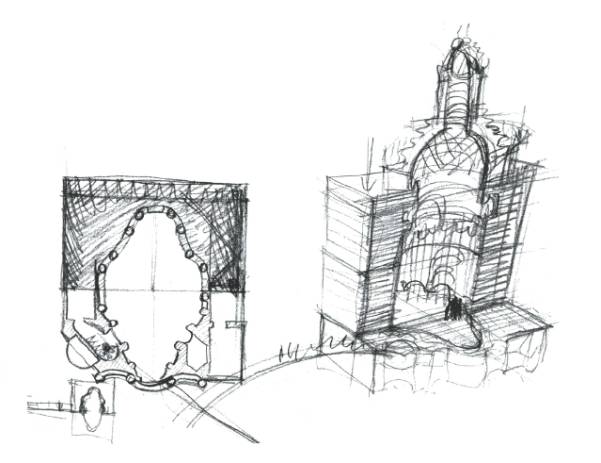

Figure 6 San Carlino (Lugano), some

Botta’s drawings

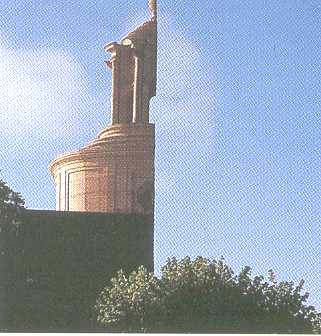

Figure 7 San Carlino (Lugano) the cross-section

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Figure 8 The self-similarity presents in the

Botta’s wooden model (rendering)

Figure 9 San Carlino (Lugano), frontal view

4. Conclusions

Francesco

Borromini was a severe artist and a serious architect, at the same time, he

took liberties with the classical system [Harbison, 2000]. Harbison affirms:

”He seems to thrive in awkward situations, cramming monumental façades into

narrow streets. Like Bernini orchestrating his vast plain, Borromini also aimed

at dramatic effects of movement, through compression not expansion” [Harbison,

2000, p. 2]. For example, the Church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane is in

agreement with the Harbison’s considerations.

The

Botta’s San Carlino performs within an alien urban theatre, that imitates the

life. It is the leading actor in the city and, at the same time, the great

absentee from the city itself, since its reality is completely Roman [Saurwein,

2001, p.9]. This Botta’s project is provocative [Emery, 1999].

Mario

Botta, with his wooden model of San

Carlino, has realized a modern reading of a Baroque work, and he has given to

San Carlino a voice in the context and in the territory where Borromini had his one’s early youth.

5. References

Bellini R. and Minazzi F., Mario Botta per Borromini: il San Carlino sul lago di Lugano, Edizioni

Agorà, Varese, 1999

Blunt

A. and Erwee M., A Guide to Baroque Rome:

The Churches, Pallas Athene

Publishers, London, 2003.

Botta M., Appunti sulla rappresentazione lignea del

San Carlino a Lugano, Botta M. and Cappellato G. (eds.) Borromini

sul lago, Skira and Accademia di Architettura di Mendrisio, pp. 13-19,

1999.

Botta M. and Cappellato G. (a cura di) Borromini

sul lago, Skira and Accademia di Architettura di Mendrisio, 1999.

Careri G., Baroques,

Princeton Univ Press, 2003.

Emery N., Volontà d’arte, Botta M. and Cappellato G.

(a cura di) Borromini sul lago, Skira and Accademia di Architettura di

Mendrisio, pp. 39-43, 1999.

Guarini G., Architettura

Civile, 1737 (reprint, Polifilo, Milan, 1968)

Harbison

R., Reflections on Baroque, Reaktion

Book, London, 2000.

Hatch

J.C., The Science Behind Francesco Borromini’s Divine Geometry, Nexus:

Mathematics and Architecture IV, Kim Williams Book, Fucecchio, 2002.

Hersey

G., The monumental impulse, The Mit

Press, London, 1999.

Hersey

G., Architecture and Geometry in the Age

of the Baroque, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2000.

Magnuson

T., Rome in the Age of Bernini,

Almquist and Wickell, Stockholm, 1986.

Papi F., von Moos S., Bellini R., and Minazzi F., Per un’architettura vivente, Centro di

Documentazione, Accademia di Mendrisio, 2002.

Portoghesi

P., Roma Barocca: the History of an

Architectonic Culture, The MIT Press,

1970.

Sala N. and Cappellato G. Viaggio matematico nell’arte e nell’architettura, Franco Angeli,

Milano, 2003.

Saurwein E. (eds), Notes on the wooden model of the San Carlino in Lugano by Mario Botta,

Gabriele Capelli editore, Mendrisio, 2001.

Schneider

Adams L., Key Monuments of the Baroque,

Westview Press, 2001.

Stella

J., Baroque Ornament and Designs ,

Dover Publications, 1987.