IMAGINED ARCHITECTURE

via

MATERIAL

IMAGINATION

A Matter of

Trans-Formation

Prof. Anthony Viscardi, B.Arch, M.Arch

Department of

Art and Architecture, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, USA

e-mail:

av03@lehigh.edu

Abstract

The pedagogical intent of this design lab was to provide a means for interactive dialogue to occur between the formal and the material modes of imagination in order to approach a tripartite structure of form, content and function. It acted as a 'bridge' between the design principles of space and form to issues of materiality, structure and modes of representation inherent in the 'process of making'. We began with several design exercises as investigations to explore the expressive potential that material can achieve in light and mass as well as in structure and detail. The students explored and emphasized the ways in which structure and materiality can supplement and compete with the notions of form and space. The primary modes of representation were plaster casts, charcoal analytiques, structural models and sectional drawings as interpretive texts. They became the vehicle--hereafter refered to as 'artifice'--to develop visual acuity in response to formal cues and to demonstrate the affinity of technique and materiality with the construction of an idea.

Introduction

Creativity in architecture can be based

on the process of transformation of matter.

This transformation occurs in the realm of perceptive imagination where

to generate and develop new ideas means to pre-figure matter in the course of

the idea's realization. Two types of imagination can be engaged in this

process, a formal imagination and a material imagination. (1) Formal

causes tend to stem from intuitive and associative image production. These images derive from psychological

projections and picturesque forms. They

usually provide an analytical reading to create an object. Yet besides these images of form a certain

type image is provoked solely and directly from our immediate confrontation,

interpretation and manipulation of matter.

These images may be assigned category by the eye but only the hand truly

reveals them. They depend on visceral

readings that are projected through qualities such as mass, material surface or

texture, light, space and time. Of

course, it is only artificially that we can separate formal and material

imagination in the process of making.

Since matter remains itself despite the

transformational metamorphosis it undergoes, the meditation upon and

manipulation of it tends to cultivate an open imagination. This allows the architect as 'maker' to

possess a kind of openness for 'wonder', preparing oneself for the amazement of

unconscious manipulations that give rise to creativity and the art of

invention. It is through a sense of

wonder that one can initiate a critical beginning to the acquisition of

knowledge. Wonder is an action--an

impassioned verb. It forces one to

think, to go beyond, to ponder in a world of constructive imagination. By seeking cues and wandering through

curiosities, one becomes involved in a play of interpretive procedures until

paradox becomes intelligible in an image of conception. Through this process of

making--a techne&poesis---we gain

an intuitive knowledge of the structure of the reality within which we dwell.

In the act of making one must engage

memory at one end and imagination at the other; memory as the recollection of

one's experiences, and imagination as the mechanism of transforming seemingly

insignificant things into meaningful

forms of re-creation. Through this dialectic the formal imagination embraces

and transforms the material and allows one to read into shapes, marks, light

and colors, a symbolic or representational meaning that is our fundamental form

of language. This form of discourse allows the roles of subjectivity and

objectivity to freely interrelate in order to discover new orders inherent in the

active process of material transformation.

The process starts from a persistent inquiry into the ways of natural

creation, the becoming, the functioning and the individual resolution to

associate oneself with the matter in which we live. John Locke said that what gives each person his or her personal identity

is that person's private store of recollections, and I might add

re-creations. "Imagination is not

merely a faculty for forming images of reality but it is the faculty for

forming images which go beyond reality, which sing reality."(2)

.

The Three Acts of Play

The three notions of form, content, and function have always

been bound together as the three important components of architectural

design. In the current heterogeneous

state of the architectural design studios in academia, these hierarchical

prescriptions or sequence of these notions have been freed from the strict

boundaries of former theoretical

paradigms. As educators though, we need

to delineate optimum design sensibilities for beginning design students to

weave together these sometimes artificially autonomous components in the making

of architecture. If we begin to view

these components as metaphorical portals that the student opts to pass through,

their order becomes particular to the personal design route for the project at

hand. Thus one can choose form; via

content, via function or via form itself.

This becomes a point of departure that frames a particular perspective

with which the student can proceed in his or her design process. Dr. Alberto Perez-Gomez calls this

theorizing the inventing of an 'enabling theory'; it enables the designer to make, serving as a rationale for

ideation and fabrication.(3)

'Artifice' as An Enabling Theory

Normally 'artifice' denotes

the skill and ingenuity one uses in the making of an artifact. There is a second connotation though that

points toward trickery and craft. These

compound notions of artifice for this

discussion are seen as a means to the articulation of form for the beginning

design student; it encompasses skill and ingenuity as well as craft. I will refer to a project called, "A

Place for One's Daydreams" to demonstrate form generating techniques, artificially divorced from content and

function, to be used as initiators in the development of an enabling theory for

the final production of an architectural project. This artificial separation of form from content and function

provides a portal to design and allows the student to focus primarily on a

tangible vocabulary in the manipulation of the constituents of form. These techniques act as vehicles in an

architectural pedagogy that open the imagination to formal and material causes

and establish orders that will eventually lead to habitable forms of

architecture. The artifice then is a

device--a particular point of view--to appropriate the functional program and

provide meaningful content to an architectural production.

The Communication of Meaning through the

Design of Structure

Each student would begin their individual exploration by deriving

their own "enabling theory" through an active process of making an

object--what I refer to as 'opening an artifice'. Through a creative means of playful inquiry the artifice becomes

the mediator to guide the student in making conscious and unconscious

discoveries in his or her design process.

These discoveries would then lead to analytical and interpretative modes

of categorization defining formal and material orders inherent in the newly

made artifact. As subsequent questions

are imposed an effort is made to find new resolutions that provide ways to

interpret the conventions of architecture.

By artificially isolating the individual levels of design resolution the

student immerses him or herself into the activity of the moment, cultivating an

open imagination. As each consecutive

proposition is given the previously made artifact becomes active in the form of

the new artifice that now actively directs design thought. The design actions take on a conjugational

character described semantically by Paul Klee in his Pedagogical Sketchbook

as, active-medial-passive. (4)

Early design exercises challenged the

students to question the nature of matter through shape, form and value,

testing their ability to 'see' and react manually to formal cues. They focused on the relationship between

mass and light and incorporated the use of large charcoal analytiques as the

visceral and manual means of seeing. This exercise acted as the point of

departure for the next series of studies dealing with structural

transformations into frameworks for the suspension of objects and eventually

enclosure systems for the habitation of their body.

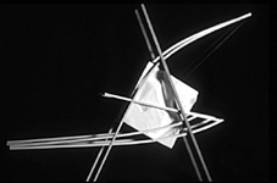

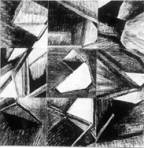

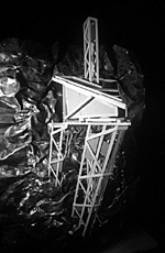

To begin, students constructed several plaster casts to act as templates for study in light; each 1" deep by 4"x4" plaster cast contained the impression of an object. As mass and light studies, these tablets were viewed gesturally through a series of large charcoal drawings to elicit a visceral and material mode of imagination. In these drawings the students were to isolate and focus their vision into small areas (1"x1") of the cast and enlarge them onto 18"x24" paper filling the field. This forced them to acutely examine the nuances of light and shadow as a means of articulating form. Simultaneously, through the use of sectional figures of pochè, the students produced ink drawings on mylar focusing on formal analytical skills in visual perception. The resulting dialogue generated imaginative pluralities that challenged their perception and manipulation of architectural conventions. Architectural drawings as interpretive texts--palimpsests of geometry in plan and section--established foundational orders in form-making. These maps would lead to 3-D frameworks exploring structural suspensions of objects; scaffolding to explore notions of the 'container as contents' versus the 'contents as container'. Axonometric drawings were constructed from the orthographic projections in order to inform a structural framework that would support and enclose these plaster casts raised 4 inches from a ground surface. Through playful experiments in tension and compression, each student wrestled with the forces of gravity to compose a structural framework that amplified the internal void left from the embedded object in their cast while also reflecting the 4"x4" dimensions of its container. The constructions were derived from direct formal extensions and material explorations of their initial artifact; the tablet. The tablets became the artifice to explore; light and mass, solid and void, and structure and gravity through drawings and models simultaneously--construing and constructing as an act of making. They were now to imagine the solid mass of their plaster tablets as a void or as the container of space.

The play of ARCHITECTURE/The architecture of PLAY

Each student now possessed an

armature to support the two acts of play to follow: function and meaning. It was after the completion of these formal

and material exercises that I introduced several architectural propositions and

asked the students to explore their meaning in relation to their unconventional

structures. The students were now

challenged to transform their models, through rigorous architectural probing,

to function as a habitable space for thought and experience. They were asked to use their working model,

as developed to this point, to design "A Space for One's

Daydreams." This space would be

for one person and be derived from the mass/void within the spatial framework

of their individual construct (the plaster cast). The architectural conventions

of wall, stair, window, light

and gravity were to be the

focus of their next formal transformations.

The meaning and function of these elements should be revealed through an

interpretation of their previously built working model and be driven through a

personal means of inhabiting their space of daydreaming. The existing model should be viewed as being at 1/4" scale, i.e.,

16'x 16'x 4' deep and 16' above the ground.

Their final model would be built at 1/2" scale, primarily out of

bas wood, to a high level of craft articulating joint and connection details.

A SPACE for One's DAYDREAMS

"... the house shelters daydreams, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace. Thought and experience are not the only things that sanction human values. The values that belong to daydreaming mark humanity in its depths. Daydreaming even has a privilege of autovalorization. It derives direct pleasure from its own being. Therefore, the places in which we have experienced daydreaming reconstitute themselves in a new daydream, and it is because our memories of former dwelling-places are relived as daydreams that these dwelling-places of the past remain in us for all time" [Gaston Bachelard- The Poetics of Space ](6)

The content or meaning of the

project would come in the form of a phenomenal proposition. Gaston Bachelard

poetically describes the phenomenology of the daydream as being a place that

"can untangle the complex of memory and imagination... for in daydreaming

we are revisiting a memory in the present and through the power of our

imagination engraving a newly formed image--an imagined recollection."

(7) Bachelard assigns this place to

the oneric house that constitutes a body of images that give oneself proofs or

illusions of stability--a place of constant re-imagining of its own

reality. Although this theme was very

abstractly stated the students were to work hard to recognize its

psychologically concrete nature.

Through their specific use of the functional and spatial architectural

elements assigned, each student confronted the challenge of making an

architectural machine "that transports the dreamer outside the immediate

world to a world that bears the mark of infinity."(8)

Each student aggressively

imposed their individual identities upon their constructions through a constant

dialogue between the individual space-images

of the world within their daydream, or one's core-space, and the natural space-images of the world without as a shell-space. In order to start their design development,

it was important for them to inhabit their construct. Through steadfastly engaging each of the assigned architectural

elements (wall, stair, window, light and gravity) as related to their

structure and appropriating their meaning as an extension of their body,

geometrically as well as phenomenologically, these architectural conventions

were each allowed to generate new and informative roles in the development of

an idea. As stated in the closing quote

by Alberto Perez-Gomez, each architectural element became a mechanism "to

identify poetic intention with architectural means." A window became a watchful eye, a stair a

way to transcend into a world apart, light a cosmological projection of time or

the protagonist to gravity. The products

of these imagined realities were real, buildable architectural constructions in

a concrete language of architectural elements.

Affording the freedom to interpret the phenomenal proposition within the

stricter constraints of the architectural program proved to convince each

student that they could build almost anything they could constructively

imagine. It allowed for memory and

imagination to playfully intertwine affording individual interpretations and

inventive applications of some basic architectural conventions. Through a play of architecture, one was

freed to examine, to interpret and to re-configure the basic constituents of

architectural design and order them into imagined recollections--or daydreams.

"The primary meanings of

architecture are sought in making,in bringing into being things, places,

sensations, perceptions; not in symbolizing meanings originating elsewhere, or

in the responsive product of requirements.

We work with wall, window, stair, light and gravity, in order to identify

poetic intention with architectural means, but without accepting any type

or a priori order. The uncertainties lying between

high-sounding intention and beautiful work are freely admitted; that is what

the struggle, panic and thrill are about." (9)

The nature and goal of these

design lab experiments were to explore two divergent paths of inquiry:

beginning with the communication of meaning through the design of structure and

concluding with the design of meaning through the communication of structure. The paradoxical nature of this affirmation

would become clearer as the students accounted for the ways in which they had

been asked to construe and construct.

Phase two of this experimental studio would attempt to form a conclusion

that could produce a negotiation between the reading of an object to design

meaning (the plaster tablets) verses using a reading to design an object. Their previous imaginative constructs have

enough constituents to say that they are 'architectural', but what makes it

architecture? Their former constructions were now viewed as 'conceptual models'

that would direct analysis, interpretation and the appropriation of a new

architectural project. They were to

build upon their previous architectural discoveries and allow them to act as

the catalyst for the design of more conventional building tasks. The students would endeavor to elicit and

transform the complex ideas, techniques and situations of their previous

architectural design project, architectonically into conventional building

tasks, complete with site, program and parti.

The

Design Of Meaning Through The Communication Of Structure

The objective of this studios'

transformation process would be to understand more fully the conventions and

conventional tools of architecture too; however, in this case, each student

would be in charge of deciding precisely how,

why, and under what conditions these conventions and tools are to be

put into practice in relation to the specificity of their former site machine,

now viewed as a conceptual model. This

would necessitate serious reflection on the formulation and application of a

building theory. Each individual must

justify how, why, and under what conditions the practical issues such as

'wall', 'floor', 'roof', 'aperture', and 'stair' address the communication of

meaning in their project. In both

studios the exercises of the first half of the semester produced several

'tangible' products. The exercises were

cumulative, in the sense that each built upon cues from its predecessor and

transformed simple issues of form into complex readings of situations. The next phase of this studios' project

required a transformation and distillation of the abundance of tectonic and

semiotic causes and effects represented in their conceptual model into specific design criteria for

individual building types that respond to the specific nature of the conceptual

model and the design methodology initiated in order to construct it.

Each student was asked to

reflect on the communitive opportunities of 'meaning' that are implicit in

their concept model as well as the formal and spatial characteristics they

possessed. As a class we tried to

isolate the potentials for design strategies that would encapsulate both

content (meaning) and container (building) simultaneously. This resulted in thirteen individual project

statements to be developed architectonically into a building, complete with

program and parti. Each project had a

'project title' or name, a 'building task' or functional frame, historical or

literary references if applicable, and a series of specific questions for the

student to ponder in their design process.

END NOTES

1. Gaston Bachelard, Water and Dreams , The Introduction- Imagination and Matter, pg. 1, 1983, The Pegasus

Foundation , Dallas, Texas.

2. Ibid.,

pg. 16

3. The articulation of the notion of

'artifice as enabling theory' was developed

through several ongoing dialogues with a good friend and former student of mine named

Kristopher Takacs. This began after we attended a lecture by Alberto Perez-Gomez at

The University of Pennsylvannia and

continued via our theoretical discussion of one of Kristopher's former studio projects.

I want to thank him for his

contribution to this paper and the ongoing discourse

of architectural design pedagogy.

4. Paul

Klee, Pedagogical Sketchbook, pp. 16-20, Frederick A. Praeger, New York, 1953

5. Kathleen Dean Moore, Riverwalking , "Winter

Creek," pp.36, A Harvesy Book,

Harcourt Brace & Co. ,1996

6. Gaston

Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, pg. 6, The Orion Press, Inc., 1964

7. Ibid.,

pg.26

8. Ibid.,

pg.183

9.

Alberto Perez-Gomez, Carleton Univ. Catalogue, 1983, Introduction