The Modular: An

Analysis into Generative Architecture

Mahnaz Shah

PhD Candidate, Architectural Association, School of Architecture London

e-mail: shah_ma@aaschool.ac.uk

Abstract

Le Corbusier’s

city grids, domestic layouts and the Modular are generally considered to be

expressive of the spatial innovations of the new sciences, thus providing an

homogenous, quantitative, infinitely extensible continuum.

Jack H.

Williamson [1986] reads this into the alleged ‘dematerialization’ of Le

Corbusier’s interiors and christens it the ‘anti-object paradigm’. He considers

this spatial development to be parallel to the loss of autonomous individuality

under the new collectivist and determinist social and psychological

sciences.

Andrew McNamara

[1992] similarly reads Le Corbusier’s grid as an evidence of a desire to

collapse all boundaries – natural, spatial, social and aesthetic – into an

undifferentiated field. Le Corbusier is apparently committed to imposing this

field at all levels, ‘to transform it into a broad social vision encompassing

every aspect of life’.

According to

Richards[2003]; although these readings maybe applicable to other modernists

grids, they are not applicable to Le Corbusier.

This Paper

proposes to challenge Richards[2003] assumptions and tries to prove that,

through Le Corbusier’s final project; the Venice Hospital 1964-65, the Modular

formulated a code that is capable of articulating dynamic, generative

architecture.

The Modular: An

Analysis into Generative Architecture

Mahnaz Shah

PhD Candidate, Architectural Association, School of Architecture London

e-mail:

shah_ma@aaschool.ac.uk

Le Corbusier tried to embed …ideas in Jullian’s mind during

their early discussion, but ultimately the most novel and powerful ideas came

in the few sketches Le Corbusier showed him later. The key to the project was

there, presented in a completely unprecedented way. Mazzariol added,

The young Chilean architect who for several years had been

living like a moine in the atelier, realized in bewilderment that something

quite unprecedented was taking place … Was this the beginning of a new

architecture? The drawings were made of few strikingly precise indications; the

form was spatial and the space developed in a regular movement like the ripples

sent out by a stone dropped into a pond. No previous design had ever evolved so

easily and so quickly.

Giussepe Mazzariol

1966

Introduction: Drawings to the Grid in Le Corbusier’s Design

Strategy

The core

challenge in translating Le Corbusier’s Venice Hospital project 1964-65

conceptual drawing remained in defining the order – the systematic content of

the project defined by repetition and numbers - understood as a given, as a matter of strategy. This design

strategy of systematic repetition remains the core element in identifying the

dynamics of the city of Venice and its replication in the form of Generative

Architecture.

According to Le Corbusier’s primary assistant in the Venice

Hospital project, Guillermo Jullian de la Fuente; the real question in the

Venice Hospital project, arose at the level of tactics; on how to manipulate

the number, the structure, the module and the pattern to become architecture –

that generates its essential dynamics.

The above discipline was mastered by rigorous calculations

and testing. Sometimes the precision of the building elements and their

sequencing in extension were so complete that the building plans turned into

virtual musical notations: One day while working on the drawings for a huge

longitudinal section, which covered the complete atelier space in Venice,

Jullian along with other assistants decided to ‘play’ the hospital building.

Each member of the team selected a different sound and Jullian assigned to each

‘instrument’ a building element – piloti, ramp, vault, partition – as ‘notes’.

Then acting as an orchestra conductor, Jullian followed the section by keeping

a constant rhythm.[1]

Although the above exercise in all probability seems

possible, it is a highly subjective approach, an abstract rationality and

therefore not feasible for further investigation unless taken as a geometric

and mathematical exercise – with the key note being the sense of or a

return to order. In an attempt to

understand this definition of order, it seems imperative to briefly examine Le

Corbusier’s architectural philosophy.

1.1 Spirit of Age – Spirit

of Geometry

Le Corbusier architectural philosophy defined the post war

1914-18 sentiments, it was an era of strong reaction against the anarchy and

uncontrolled experimentalism of the pre-war avant-gardes. As such, according to

Colquhoun [2002], a ‘return to order’

was deemed necessary. For some French artistic circles this meant a return to

conservative values and for others it meant an embracing of the imperatives of

modern technologies. The situation was further rendered complicated by the

assimilation of cultural pessimists like the poet Paul Valery and technological

Utopians like Le Corbusier both invoking the spirit of classicism and geometry.[2]

Banham [1960] believed that Le Corbusier defined a specific

modern sentiment found in the ‘spirit of geometry’ with exactitude and order

and its essential condition.[3]

This sentiment according to McNamara [1992], equally sought to encompass more

than a reductive functionalism derived from the logic of contemporary economic

processes. The mix of the mass, the serial and the geometric provided a recipe

for uncovering the gestalt of a higher aesthetic and spiritual order.[4]

Ozenfant, Le Corbusier’s colleague in the 1920s remarked

that, ‘mass production had led to the desire for perfection’[5]

thus implying that it led to an ideal model but not an end in itself. He

maintained that all human perception is gauged through a geometric filter of

sensations, and argued that since it is one of man’s passion to disentangle

apparent chaos, then mathematics, geometry and the arts are all forms of

apparatus that reduce the incomprehensible to credible forms.[6]

According to McNamara [1992], the technological viewpoint of

the avant-garde owed much to the mystical, theosophical and Neo-Platonic

interpretation of art characteristic of Itten or Kandinsky. Schlemmer’s diary

entry of 1915 marked the impact of these ideas on his early artistic

formulations: ‘The line is traced with pure cold calculation; crystal appear;

cubic forms. Universal application towards the mystical.[7]

Schlemmer referred to the path towards the incomprehensible

in the simple basic forms – while Ozenfant subsequently proclaimed the

transformation of the incomprehensible into credible forms. These somewhat

mystical declarations could be readily channeled into rhetoric advocating the

establishment of objective criteria necessary for the new order of rational precision, while still maintaining a

pronounced spiritual emphasis. In response to the reformulations of these

conceptions, Schlemmer raised what became a common concern amongst the

avant-garde – a search for fundamental constants found in ‘credible forms.’[8]

It may have been this search of ‘credible forms’ in

formulating an ideology of modern painting, that Le Corbusier along with

Ozenfant developed many of architectural ideas/philosophy that was later

documented in L’Esprit Nouveau. According

to Colquhoun [2002], in Apresle Cubisme

[1918] and in the essay ‘Le Purisme’[9]

an idea that played an important part in Le Corbusier’s architectural theory

was introduced, that of the object-type.

In these texts the authors praised Cubism for its simplification of forms along

with its method of selecting certain objects as emblems of modern life. Ozenfant

and Le Corbusier claimed that, ‘ of all the recent schools of painting, only

Cubism foresaw the advantages of

choosing selected objects…but by a paradoxical error, instead of sifting

out the general laws of these objects, Cubism showed their accidental aspects.’[10]

Thus by virtue of these general laws, the object would become an object-type its Platonic forms resulting

from a process analogous to natural selection, becoming ‘banal’ and susceptible

to infinite duplication, the stuff of everyday life.’[11]

1.2 Geometry, Mathematics and Art Combined

According to McNamara, Geometry, mathematics and art

combined to realize the universal forces – regulated, measured and complete and

thus shifted everything from the domain of ‘sensory origin to that which excludes

natural doubt’[12] –

corresponding to Wells pronouncement of the imminent movement ‘from dreams to

ordered thinking’.[13]

Le Corbusier similarly proclaimed an elevation to the

spiritual in art. For him geometry represented ‘the language of man’[14]

and he aimed to transform it into a broad social vision encompassing every

aspect of life. His starting point for this was ‘that key site of modernity –

the metropolis – as is evident in his Voisin

Plan of 1925.’[15]

In this proposal for restructuring Paris, a grid plan was devised as means of

evoking the precise and harmonious relations that only become possible in the

‘great epoch’.

As he wrote in Towards

a New Architecture: the spirit of functional utility found expression in a

sense of order: The regulating line is

a satisfaction of a spiritual order which leads to the pursuit of ingenious and

harmonious relations … The regulating line brings in this tangible form of

mathematics which gives the reassuring perception of order.[16]

1.3 The Grid – the Modern Metropolis: Towards A

Generative Architecture

According to McNamara, in the Voisin Plan Le Corbusier

used the grid layout to bring the modern metropolis into line with the ideal

relations that had only been glimpsed in mass production. The plan also

revealed that social utility and aesthetic form could be identical in the grid.

The plan lived up to its name by employing notions of bordering or neighboring

as a central device. The design, however did not simply aim to suggest any

continuum of adjoining patterns and endless additions – neighboring. Rather it

sought to elaborate and weave the order of all orders at the base of chaos –

this characteristics remains an important definition of generative

architecture.

Voisin evokes a design

which is at once, a founding base and also its most elevated and refined form.

The grid thereby erases its imprint as artifice by mapping the structural form

of the city which enables ease of passage through the chaotic energy of the

modern metropolis.

Recalling the grand schemes of Sant’Elia, the project

emphasizes conjunction and flow and acts as an ‘inhering mechanism inseparable from the body of the world and operating on

it from within.[17]

The process of geometric filtering ideally constituted a form of dispersal

rather than a centralization of the ‘scopic drive’[18]

it offered a creative silencing of the urban cacophony and the confusion of

form.[19]

Hence the grid functioned as the ideal exemplar of the

generative architecture; ‘progressive’

order, operating not as an aesthetic reflex but as the pure equivalence of the

system it aimed to engender.

It also implied mathematical exactitude and the equality of

all co-ordinates in an infinite extension,[20]

thereby acknowledging the essence of uncertainty and change. Le Corbusier was

very aware of this characteristic of the grid.

This characteristic of grid may have been the key element in

Le Corbusier’s final drawing for the Venice hospital project – juxtaposing

geometric order with spatial programming into an emblematic generative architecture.

Retracings: From the Plan

to the Grid in Le Corbusier’s Design Strategy

Venice Hospital was planned in 1964 to be built in San

Giobbe neighborhood, in the Canareggio area at the edge of the city of Venice,

it was commissioned to cater for the acutely ill. The proposed hospital was unique in its design considerations, as

the challenge was not just to design the hospital, but also to design the

topography of the structure beneath the hospital - thereby creating a physical

extension to the city of Venice.

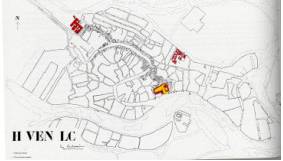

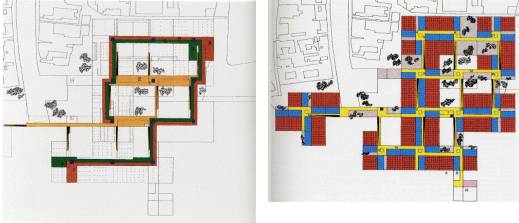

Figure 1: Atelier Julian, plan of

Venice with new hospital [third project], 1966.

2.1 Rapport Technique

In the Rapport Technique discussed below, Le Corbusier

evokes both the programmatic issue and the flexibility issue in discussing the

design of the hospital. The report turns to the problem of horizontal

circulation that sprawl would create and proposes mechanization as the means of

solving it. By virtue of its location and its scale, the building turned in on

itself and created its own interior subenvironments in the form of wards

centered around courtyards that repeated in a seemingly endless manner. These

courtyards were supposed to extend the residential areas of the city into the

water, but also create an abstract, clear logic that reciprocated back onto the

labyrinthine context of Venice.[21]

The Hospital is sited near the northwest end of the Grand

Canal and extends over the lagoon separating Venice from Mestre. The decision

to contain the wards in a solid wall and to light them from the roof is

justified by the proximity of the railway terminal and the industrial squalor

of Mestre. The building covers a large area and is comparable in its mass and

public importance to such groups as the Piazza San Marco, the Ospedale Civile

and the monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore. It therefore forms an important

addition to that small but significant collection of buildings symbolizing the

public life of Venice.[22]

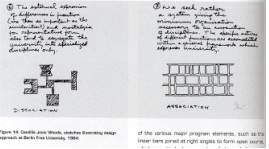

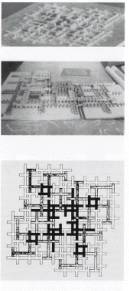

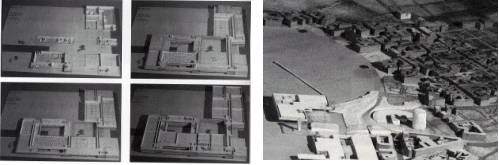

Figure 2: Atelier Jullian, model of the Venice

Hospital, 1966

Unlike the assimilation of the Venice Hospital to its

immediate surroundings and everyday life, Kenneth Frampton[23]

points out that the Metabolist were unable to find such harmony in their work.

According to Frampton, Kiyonari

Kikutake’s floating cities are among the most poetic visions of the Metabolist

Movement, yet Kikutake’s marine cities seem even more remote and inapplicable

to everyday life…[24]

Gunther Nitschke et al. had this to say when making an assessment of the

Metabolist Movement in 1966:

As long as the actual building get heavier, harder, more and more

monstrous in scale, as long as architecture is taken as a means of expression

of power, be it of oneself or of any kind of vulgar institution, which should

be serving not ruling society, the talk of greater flexibility and

change-loving structures is just fuss. Comparing this structure [Akira

Shibuya’s Metabolic City project of 1966] with any one of the traditional

Japanese structures or modern methods suggested by Wachsmann, Fuller, or Ekuan

in Japan, it must be considered a mere anachronism, a thousand years out of

date, or to say the least, not an advance of modern architecture in terms of

theory and practice.[25]

Le Corbusier was determined not to unsettle the existing

typology of Venice through his proposed Hospital project. Le Corbusier wanted

to translate his perception of the city in his design, according to him; “one

cannot built high; it would be necessary to be able to build without building. And then its necessary to find scale.”[26]

(emphasis mine)

Although Le Corbusier was not alone in his pursuit to find a

balance between the concept of innovativeness and integration in his design

solutions[27], his

solution according to Colquhoun, combines the monumentality of the Hospital as

part of the grandeur of the city with an intimacy and textural quality in

harmony with the city’s medieval scale. If built, it would have gone a long way

towards revitalizing the “kitchen sink” end of the city which needed more than

the tourist trade to keep it alive.[28]

Incidentally, Eric Mumford in his essay[29]

believes, Le Corbusier’s concept of ‘ineffable space’ as a new basis of

architectural form, articulated in a 1964 essay, usually relied on the

transformation of existing typologies.

In comparison, Candilis-Josic-Woods, were attempting to

generate a new method of formal expression that loosely linked the various

program elements in ways that allowed to continuous flexibility and change.[30]

As in the example of the sketches illustrating the design approach at Berlin

Free University, 1964.

Figure 3: Candilis Josic Woods,

sketches illustrating design approach at Berlin Free University, 1964.

Although this approach was different from both Le Corbusier

and Blom[31], the idea

of linking elements that form open courtyard and connect programmatic areas has

been extensively utilized by Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret in works such as

the Centrosoyuz in Moscow, the League of Nations competition entry in Geneva,

the Salvation Army Cite de Refuge in Paris and the Palace of the Soviets

competition entry in Moscow, as Colquhoun had perceptively analyzed. Colquhoun

identified how these projects begin to indicate a new urban pattern with

multilevel circulation systems, which at the same time are adjusted to the

particularities of each projects complex urban site.

Figure 4: Piet

Bloom, “Noah’s Ark” project for urbanization of the Netherlands, shown at Team

10 meeting at Abbaye Royaumont, 1962; model photos and plan of one village

unit.

In each, Le Corbusier perfected the technique of

elementarization of the various major program elements, such as the linear bars

joined at right angles to form open courts, which permitted a large number of

plan variations with potentially infinite extensibility.[32]

Le Corbusier was able to realize such projects only in greatly reduced form,

but Candilis-Josic-Woods began to build such ideas in enlarged but at the time

spatially limited projects such as the Berlin Free University.[33]

Although Eric Mumford in his arguments cites the example of

the Berlin Free University, it must be noted here that in an assessment[34]

of this University by Tzonis et al. The Berlin Free University is somewhat

termed as a magnificent yet redundant structure in its present condition.

Unlike Le Corbusier’s proposed Venice Hospital it remains an isolated part of

its immediate infrastructure, in terms of its scale as well as its functional

programming.

2.2 Plan of the Venice Hospital

In terms of the plan of the Venice Hospital, Le Corbusier

integrates the communication channels, the recreational and religious centers

along with immediate hospital personnel space in the ground level of the

hospital. According to Colquhoun, “The ground level accommodation occupies an

L, with an isolated block contained within the arms of the L. The reception,

the administration, and the kitchen occupy the L, and the nurses hostel the

isolated block. A straight access system breaks through the L where gondola and

car entries converge onto a common entrance lobby thrown across the gap.

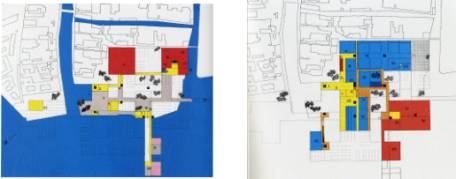

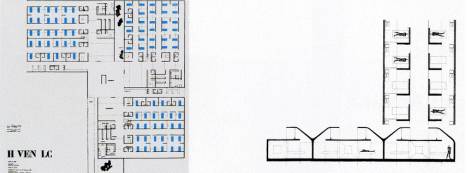

Figure 5: Le Corbusier, Venice Hospital, Figure 6: Le Corbusier, Venice Hospital, first

first project [1964]

level 1. project level 2a [1964]

The gondola approach route is bridged by a route linking

religious and recreational centers at its extremities. There is an entresol

containing extensions of the ground level accommodation….(similarly) the

analytical and treatment departments are on the level 2a are arranged freely

around the cores in an analogous way to the wards above.

Figure 7: Le Corbusier, Venice Hospital, first project Figure 8: Le Corbusier, Venice Hospital, first project [1964] level 2b level 3.

Level 2b consists of a horizontal interchange system between

all elevators points – patients using the central and the staff the peripheral,

corridors fig…. The ward block which is occupies the entire top floor, is both

the largest department of the building and represent its typical element, and

organization allows this element to extend to the limits of the building with

which it becomes identified by the observer, whatever position he may be in.

The basic unit of the plan and its generator is a square

groups of wards rotating around a central elevator core – Le Corbusier calls a

campiello. These units are added in such a way that wards next to each other in

adjacent units merge, thus ‘correcting’ the rotation and making the independent

systems interlock. An agglomerate of units creates a square grid with a

campiello at each intersection. The plan differs from those isomorphic schemes

where the unit of addition is elementary (as implied, for instance, in the roof

of Aldo Van Eyck’s school at Amsterdam).

Here the basic unit is itself hierarchically arranged, with

biological rather than mineral analogies, and capable of local modification

without the destruction of its principle…The concept of the top-floor plan is

reminiscent of the Islamic medresehs of North Africa, where subcommunities of

students’ cells are grouped around small courtyard, forming satellite systems

around a central court. As in the medresehs the whole dominates the parts, and

the additive nature of the schema is overlaid with a strong controlling

geometry.

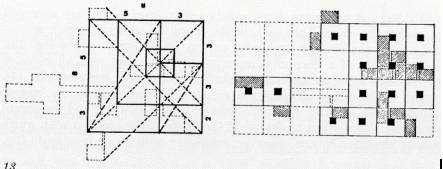

The geometric as apposed to the additive schema consists of

a system of overlaid squares and the golden-section rectangles. The smaller of

the two squares established a center of gravity asymmetrical in relation to the

scheme as a whole and related to it diagonally. This center is also on the

intersection of the rectangles formed by dividing the total square according to

geometrical proportion. The additive grid consists of eight units, which allows

for division of the Fibonacci series into 8, 5, 3, 2. The center of the small

square is the center of gravity of the treatment department and the main

vertical circulation point for the patients around which there is an opening in

the top floor giving light to the ground-floor court which wraps around the

central core. As at the monastery of La Tourette, the traditional court with

circulation around it is modified by a cruciform circulation system on its axis

– a typical Corbusian superimposition of functional and mythic order.

Figure 9: Showing the Venice Hospital, geometrical schema(left),

additive schema (right).

The central core (which from another point of view is merely

one of a number of equidistant elevator cores) assumes a fixed relationship

with the southeast and southwest faces of the building only. Conceptually, the

building can extend on the northeast and northwest faces, and these are

developed in a freer way over the lagoon to the northwest and the Canale di

Cannaregio to the northeast, where one assumes further extension could take

place. (Colquhoun notes that; between the first and second project a new site,

became available, and it is therefore possible to see how extension has been

achieved without detriment to the overall schema.)

The wards are grouped around the central light well in a

wing over the lagoon, and form a U – shape over the gondola entrance to provide

the echo of an avant-cour. From this “soft” side a bridge extends over the

canal to an isolated ward complex on the opposite side.

According to Colquhoun; despite the uniqueness of this

building in the work of Le Corbusier – a uniqueness that perhaps can be

explained by the complexities of the problem and by the peculiarities of the

site – a number of prototypes exist in his earlier work(that can perhaps

testify to the feasibility of his design solution for the Venice Hospital). At

the Villa Savoye in Poissy the flat cube, projected into the air and open to

the sky, was first established as a “type” solution. It seems clear that this

sort of “type” solution cannot be equated with the object-type discussed by

Banham in his Theory and Design in the

First Machine Age, since Le Corbusier frequently uses the same type in

different contexts. However it can be assumed that Le Corbusiers’ concept of

type relates to a mythic form rather than to a means of solving particular

problems, and that, as with physiognomic forms or musical modes, a number of different

contents can be attached to the same form. A similar idea is apparent in the

project of for the Museum of Endless Growth of 1930-39, also connected with the

problem of extensibility as at Venice, though solving it in a different way. In

the 1925 Cite Universitaire project a solid single-story block of studios was

proposed, where the rooms were lit entirely from the roof.”[35]

In the Venice Hospital patios are more than just the static

result of a solid that has been carved out to gain light and air. Following the

explorations started at the 1964 Carpenter Center in Cambridge, the interaction

of the inside and outside spaces are consciously activated by means of layers

of transparencies and visual fluidity that dissolve the void and penetrate the

mass. The idea successfully solved the contextual difficulties faced in the

Harvard Building by dematerializing the facades and the limits of the envelope,

and projecting the surrounding buildings as the ultimate façade. In Venice this

effect is intensified by the shimmering reflections of the sun on the water and

its projections on the slabs, walls, glassed surfaces, and pilotis.

The idea of a building on pilotis extending over water, may

stem from Le Corbusier’s earlier interest in reconstructions of prehistoric

lake dwellings in central Europe. The monastery of La Tourette resembles such

schemes through the way in which the building is projected over rough sloping

ground which, like water, offers no foothold for the inhabitants of the

constructed world suspended above it.[36]

Thus in the hospital scheme the potential symbolism of these

forms has been harnessed to a new and unique problem. The space of the pilotis

forms a shaded region in which the reflections of sunlight on water would

create continuous movement. Over this space, which is articulated by numerous

columns whose grouping would alter with the movement of the observer, floats a

vast roof, punctured in places to let in the sunlight and give a view of the

sky. This roof is in fact an inhabited top story, whose deep fascia conceals

the wards behind it. It is the realm of the sky in whose calm regions the

process of physical renewal can take place remote from the world of water,

trees and men which it overshadows. But apart from its suggestions of sunlight

and healing, it has more somber overtones.

The cavelike section of the wards, the drawn representation

of the sick almost as heroic corpses laid out on cool slabs, the paraphernalia

of ablution suggests more personal obsessions and give the impression of a

place of masonic solemnity, a necropolis in the manner of Claude-Nicolas Ledoux

or John Soane.

Figure 10: Atelier Jullian, Venice Hospital, Detail plan and section of typical

3rd project; Detail Plan of patients

rooms patient cells, 1965

layout [level 3], 1966

The analytical way in which the constituent functions are

separated allows them to develop pragmatically around and within fixed

patterns. The form is not conceived of as developing in a one-to-one relation

with the functions but is based on ideal schemata with which the freely

deployed functions, with their possibilities of unexpected sensuous incident,

engage in a dialogue. The building is both an agglomeration of basic cells,

capable of growth and development and a solid which has been cut into and

carved out to reveal a constant interaction of inside and outside space. The

impression of complexity, is the result of a number of subsystems impinging on

schemata which, in themselves, are extremely simple,”[37]

yet elegant as is evident in the Rapport Technique[38] by Le Corbusier. The Rapport is a detailed

listing of functions of the Hospital – from outpatients, department to

emergency services, to performance space, public square, hotel, school, shops,

lecture rooms, chapel, and the morgue – and the different user group, each

given their place in this tapestry, conveying a strong urban feel.

The Rapport[39]

suggests strong emphasis on technological enabled circulation and communication

systems so as to make the vast horizontal spread operate tightly. The three

main iterations of the Venice Hospital were produced between 1964 and 1966.

“The broad strokes are set in the first, the programmatic complexities are

worked out in the second, and in the third the construction logic begins to

appear.

Fig…..illustrate respectively the projects’ conceptual

outline, its urban density, and the programmatic compartmentalization and logic

of internal circulation.

2.3 Programmatic consideration of the Venice Hospital

Project

Below is a brief comparison of the programmatic

consideration of the Venice Hospital as outlined in Le Corbusier’s Rapport Technique (1965) with Alex Wall’s

“Programming the Urban Surface” (2001).

The Venice Hospital as opposed to the classical conception

of hospitals built and organized vertically, was a ‘horizontal hospital.’ Three

main levels were planned.

The first level, on the ground is the level of connection

with the city; there one finds the general services and all public access – by

water, by foot, and from the bridge across the lagoon.

The second level is the story of preventive care, of

specialized care, and of rehabilitation. It is a level of medical technology.

The third level is the zone for hospitalization, and the visitor area. The

height of the level is 13.66 meters; this dimension corresponds to the average

height of the buildings in the city….

The point of departure for the hospital was the room

[cellule] of the patient. This element, created at the human scale, gave rise

to a care unit, of twenty eight patients, which functions autonomously. This

unit is organized around a central space of communication (Campiello) and four paths (Calle),

which are intended for both circulation and inhabitation by patients in

convalescence. Four units of care form a ‘building unit.’ Through the juxtaposition of building units, this framework yields a

horizontal hospital. Thus the hospital stops being a static organism and

acquires a flexibility required both to follow the evolution of medical

innovations and to accommodate the possibility of future growth. The hospital

department can be interchangeable and will be used in accordance with the

changing needs of the hospital. The care units receive indirect natural light

that helps to create the best possible conditions for the patients. On the same

level the patient will find the conditions of the city life, upon entrance into

the “Calle,” the Campiello,” and the hanging gardens.

For the patient, a more comfortable hospitalization

represents, in fact a more effective cure, which is always more economical.

This means that one must go beyond the step of curing and emphasize the

preventive and rehabilitation capabilities of the hospital. This process presumes a medical organization

based on teamwork, and for this reason the second level is conceived in such a

way that the medical services that it contains….can be used indiscriminately by

all hospitalization services. This level is exclusively reserved for the

medical staff, except for the circulation space, which is directly linked to

the first floor and is used for prevention and rehabilitation…

By opening the ground floor directly onto the city, one

allows for a city-hospital encounter and facilitates the visual transmission of

medicine towards the outside. In this way the outpatient … will find himself within reach of all the services that facilitates their contact with a

hospital (prevention, therapy, rehabilitation). The hotel, the restaurant, the

cinema, the shops, etc,. will effectively enable this integration with the city,

allowing many patients to be treated without being hospitalized, and thereby

allowing the beds available inside the hospital to be occupied more

reasonably….. The Unite de soins, the

Campiello, and the Calle serve to create relationship

between the patient and the city.

The various specific functions – patients check in,

emergency care, visitors, etc. - are all given a point of contact with the

ground at level 1, which is organized vertically to lead to their corresponding

levels and spaces. The horizontal network of shallow ramps on the fourth floor

is reserved exclusively for the patients and medical staff; it ensures their

circulation all the while prohibiting the passage of patients into the services

areas where they do not belong. The fifth story is thereby left entirely for

the use of hospitalized patients and their visitors.”[40]

Similar design consideration is formulated by Alex Wall in

his argument, according to him the “goal of designing

the urban surface is to increase its capacity to support and diversify

activities in time – even activities that cannot be determined in advance –

then the primary design strategy is to extend its continuity while diversifying

its range of services. This is less design as passive ameliorant and more

as active accelerant, staging and setting up new conditions for uncertain

futures.[41] He further

believes that the “traditional notion of the city as a historical and

institutional core surrounded by postwar suburbs and then open countryside has

been largely replaced by a more polycentric … metropolis. Here multiple centers

are served by overlapping networks of transportation, electronic communication,

production and consumption. Operationally, if not experientially, the

infrastructures and flows of material have become more significant than static

political and spatial boundaries. The influx of people, vehicles, goods and

information constitute … “daily urban system” painting a picture of urbanism

that is dynamic and temporal.[42] The emphasis shifts here from forms of urban

space to process of urbanization, processes that network across vast regional –

if not global – surfaces.[43]

Unlike the treelike[44],

hierarchical structures of traditional cities, the contemporary metropolis

functions more like a spreading rhizome, dispersed and diffuse, but at the same

time infinitely enabling[45].”

According to Guillermo Julian de la Fuente, he tested the

urban ideas considered in the Venice Hospital at a broader scale between 1969

and 1970 in a competition project for the renovation of the waterfront of the

city of Cuomo.

Figure 11: Jullian, sequence of

models Figure12: Jullian,

competition project for the urban depicting spatial relations in patios renovation of Cuomo, Italy

1979-70.

Final Version 1970.

After visiting and analyzing the city, studying its Roman

fabric, and reviewing the spatial relations of Giuseppe Terragni’s work, Julian

decided to deploy a new urban fabric that following Venice’s example, included

major public programs and amenities such as theatres, exhibition halls, and

parks. “The structure is permeable to the lake underneath” he said. “Without

facades, this structure is in reality conceived within the spirit of an open

and flexible program.”[46]

For Jullian, the Cuomo project is part of the same research he undertook for

Venice, in this case taking the Roman city as a starting point. Here the

project is a reiteration of the Venice principles, but influenced by the

existing plan of the city and its texture. For Julian, projects like Cuomo or

Valencia are part of that continuous search for ways to operate at such scale,

and these experiments generated a process of cross-referencing that always

converged on Venice as a point of departure and arrival.[47]

As Julian puts it; “It is very important to remark that the

idea was not to create a block or wall towards the city … In Venice there is

this special characteristic called the “transenna,” that is the way buildings

water and light merge into a completely different condition where there are not

single buildings any more but generates a whole architectural compound.[48]

This architectural compound is an active entity, the

“activity becomes a way of describing both the presence of a building, as well

as the presence of an urban field.”[49]

According to Hashim Sarkis, in the Venice Hospital; “the

programmatic-change kind of flexibility caters to shifting functions within the

building and to growth both outward and inward. Relocating departments within

this framework is made easier by the layering of the hospital into three

strata….The radical change in the Venice Hospital is in the way the building

transform into a series of network themselves and these networks acquire their

shape from an external rather than a programmatic source. The horizontal and

block attributes of the hospital are juxtaposed against, rather than derived

from, the program. They come from the city. The growth of the hospital is also

made in increment of the city, not in increment of the internal module. Thereby

articulating in essence an excellent example of generative architecture.

The urbanization of the building program made possible the

consolidation of this scale of institution with modern life. This is one of the

main attributes of the Venice Hospital and one that distinguishes it from other

iconic mat buildings like the Berlin Free University.”[50]

The Berlin Free University remained the key example in the ‘Rational

Architecture’ sensibilities of the 1960s.[51]

Conclusion

As noted above, Le Corbusier’s city grids, domestic layouts

and the Modular do merit a consideration, as an ideal example of the spatial

innovations of the new sciences, thereby providing a homogenous, quantitative,

infinitely extensible continuum.

Jack H. Williamson read this into the alleged

‘dematerialization’ of Le Corbusier’s interiors and christens it the

‘anti-object paradigm’. He considers this spatial development to be parallel to

the loss of autonomous individuality under the new collectivist and determinist

social and psychological sciences.[52]

Andrew McNamara similarly read Le Corbusier’s grid as an

evidence of a desire to collapse all boundaries – natural, spatial, social and

aesthetic – into an undifferentiated field. Le Corbusier is apparently

committed to imposing this field at all levels, ‘to transform it into a broad

social vision encompassing every aspect of life’.[53]

According to Richards; although the above readings may be

applicable to other modernists grids, they are not applicable to Le Corbusier.[54]

In contrast to Richards, Stoppani in her essay entitled, The Reversible City:

Exhibition(ism), Chorality and Tenderness in

Manhattan and Venice [2005]

believes that

both Manhattan and Venice represent unsolved

complexities for the

modernist

discourse in architecture[55]

and therefore the Venice Hospital project

did

support Le Corbusier’s articulation of an infinitely

extensible continuum. And

a ideal place to

explore generative architecture.

According to

Stoppani [2005], Anti-modern (Manhattan) and Venice

Hospital

project

in its attempt at replicating the intrinsic program of the city may have pre-

modern

(Venice), resist the separations and classifications that the language of

the

Modernist discourse in a architecture imposes on the urban space…While

the many

different worlds of Manhattan coexist because

they are separated and

con-tained (held together and held inside) by the Grid, Venice is regulated in her

structure but is never contained inside a defined

envelope: the interior of Venice

flows, overruns, changes, constantly redefines its

boundaries. The chorality of

Venice is a collective and constitutive process. Here even the

voice of

modernism

capitulates.[56]

In Sur Les Quatre Routes (1941) Le Corbusier

acknowledges:

‘Venice is a

totality. It is a unique phenomenon […] of total harmony, integral

purity and unity

of civilization.’ ‘Here everything is measure, proportion and

human presence.

Go into the city, in its most hidden corners: you will realize that

in this urban

enterprise one finds, everywhere, tenderness

[tendresse].’[57]

Stoppani goes on to question whether this

Venetian tenderness a product of its ‘total harmony, integral purity and

unity’, ‘measure, proportion’.

It seems Le Corbusier believed that this

certainly was the case. Stoppani argues that; Venetian architectural

tenderness – Venice making as a process – seem more attuned to the fluidity of

current post-compositional trends in architecture.[58]

Or more specifically generative architecture.

Le Corbusier’s Venice Hospital project 1964-65 may have been

the first and perhaps the finest example in this direction towards of

generative architecture.

Bibliography

1.

Alan

Colquhoun, ‘Return to Order: Le Corbusier and Modern Architecture in France

1920-35’ Modern Architecture 2002

2.

Alan

Colquhoun, “The Strategies of the Grands Travaux,” in Modernity and the

Classical Tradition (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1989)

3.

Alan

Colquhoun, Essays in Architectural

Criticism: Modern Architecture and Historical Change

4.

Alex Wall

drew his formulation from James Corner, “Field Operations,” (unpublished

lecture notes).

5.

Andrew

Benjamin, “Opening Resisting Forms: Recent Projects of Reiser and Umemoto,” in

Reiser and Umemoto – Recent Projects. 40 Academy Editions, 1998

6.

Christopher

Alexander, The City is not a Tree.

7.

David

Harvey, The Condition of Post Modernity (Cambridge, Mass., Blackwell,

1989)

8.

David Havey,

Jusice, Nature and the Geography of Difference (Cambridge, Mass.,

Blackwell, 1996)

9.

George

Baird, “Free University Berlin,” AA Files 40 [Winter 1999]

10.

Giles

Delluze and Felix Guattari, “Rhizome” in A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and

Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 3-27; and

Corner , “Field Operations.”

11.

Hashim

Sarkis, ‘The Paradoxical Promise of Flexibility,’ in Case: Le Corbusier’s Venice Hospital and Mat Building Revival.

(2001)

12.

J. Derrida,

‘Cogito and the History of Madness’ in Writing and Difference trans.

Alan Bass, 1978

13.

J.S. Adams,

ed., Association of American Geographers Comparative Metropolitan Analysis

Project: Twentieth Century Cities, vol,4(Cambridge, Mass.,

Ballinger,1976)

14.

Jack. H.

Williamson, 1986,

15.

Kenneth E.

Silver, Esprit de Corps: The Art of the Parisian Avant-Garde and the First

World War 1914-1925 Princeton 1989 p.381-9 cited in Colquhoun 2002

16.

Kenneth

Frampton, ‘Place, Production and Scenography: International Theory since 1962’, Modern Architecture: A Critical History. 3rd

edition.

17.

Le Corbusier, Sur

Les Quatre Routes (1941), (Paris: Dënoel/Gonthier, 1970)

18.

M. de

Certeau, The Practice of Everday life trans. S. F. Rendall, Berkeley

1984.

19.

Mahnaz Shah,

Comparative Analysis: VH and BFU Research Seminar: Precedent and Identity TUDelft 2005

20.

McNamara,

1992

21.

McNamara,

Between Flux and Certitude: The Grid in Avant Garde Utopian Thought’ Art

History vol.15 no.1 March 1992

22.

Ozenfant and

Jeanneret, ‘Purisme’ L’Esprit Nouveau no.4 October 1929,

23.

Ozenfant, Foundation

of Modern Art trans. J. Rodker, London 1931

24.

R. Banham, Theory

and Design in the first Machine Age

1960

25.

Rem

Koolhaas, “Whatever happened to Urbanism?” in S,M,L,XL. (New York:

Monacelli Press 1995), 958-97; Stan Allen “Infrastructural Urbanism,” in Scroope 9 (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Architecture School, 1998)

26.

S. Kwinter,

‘La Cita Nuova: Modernity and Continuity’ Zone no. ½

27.

Schlemmer,

‘Diary – November 3, 1915, cited in Tut Schlemmer, ed., The Letters and

Diaries of Oskar Schlemmer 1982

28.

Shadrach

Woods, “Free University Berlin,” World Architecture 2 (1995)

29.

Simon

Richards, Le Corbusier and the Concept of Self. 2003

- Terresa Stoppani, The

Reversible City:Exhibition(ism), Chorality and Tenderness in Manhattan and

Venice 2005