HUNTING DESIGN MEMES

IN

THE ARCHITECTURAL STUDIO

Student

projects as a source of memetic analysis

Roel Daru, Eindhoven University of

Technology, The Netherlands

r.daru@iae.nl

Abstract

The current practice in design programming is to generate

forms based on preconceptions of what architectural design is supposed to be.

But to offer adequate morphogenetic programs for architectural design

processes, we should identify the diversity of types of cultural replicators

(memes) applied by a variety of architectural designers. In order to explore

the variety of replicators actually used, around hundred 4th year architectural

students were asked to analyse two or three of their own past design

assignments. The students were invited to look for the occurrence of evolutionary

design processes. They were requested to try and find some traces of memetic

‘transmission’, ‘variation’ and ‘selection’ in their own design assignments.

Some of them have described their design processes in very broad terms, others

on the contrary have made their analyses in a much more detailed way.

Although the students were also

encouraged to identify non evolutionary processes in their own design work, no

one came up with more than a few exceptions in some particular phases where for

instance no variant was considered and developed.

Introduction

How does an architectural design come into being? Does it

evolve? Is it possible to apply Darwinistic evolutionary principles from

biology to a cultural phenomena like architectural design? To shed more light

on these follow-up questions an

exploratory study is carried out. About architectural designing, many theories

and propositions were made in the past. There are impressive lists of

literature about design theory, design methods, empirical design studies and so

on. The literature might be devided in many different ways, but often one of

the types considered will be evolutionary. Here I will explore this line of

approach usually taken by people working in the fields of generic art and

architecture.

According to Philip Steadman’s book about ‘The Evolution of

Design’ (1979) the historical roots of evolutionary explanations extends back

beyond the 19th century. In the 19th century a theory of cultural evolutionism

was established, based on the analogy with biology before and after Darwin

(1859/1985). Here I want to proceed on this theory of cultural evolutionism,

but now based on the recent findings of molecular biology as an analogy. This

theory is already elaborated by Derek Gatherer (1999) for the technical design

world, where useful inventions have the upper hand. In this paper, I want to

extent Gatherer’s explanations to the world of architectural design, where

(besides usefulness) expressive innovations are at stake. To back up his theory

Derek Gatherer has discussed the work of inventors like Edison. The work here

presented is a step further on the way to empirical testing, because I asked

the (upcoming) designers themselves, instead of consulting literature about

their work (or work of practising architects). Most students were curious about

their own design activities and eager to analyse their own design projects.

Fellow teachers asked me about what they had overheared from conversations

between students.

In this paper I will argue about the theory used, the method

to approach the theory, the results of the applied method, conclusions as a

reply to the questions postulated and some remarks about the utilisation of the

results.

Theory

To answer the question about the origins and mechanisms of

architectural designing, we will explore here the possibilities of application

of Darwin’s theory of (natural) evolution. But than as it is restated first by

Dawkins (1983) in a generalised way (to include every evolving system) and

second as it is applied by Gatherer to explain the evolution of (mostly

technical) design(ing). In all those cases three features should be involved to

call a system evolving in the Darwinistic sense. A true evolving system should

have:

•

retention

or heredity,

in the sense that offspring inherit characteristics from their parents or more

general heredity information could be replicated or transmitted somehow,

•

variation

or differences

as errors creeping in in the replicator to avoid offspring with identical

features, making it impossible to choose among them and preventing the system

to evolve,

•

selection

or preferences

by an environment in which some varieties are better in surviving than others

thanks to their non-identical features, propagating their frequency in the

population involved.

If some of these features or criteria are missing, no real

evolving system will ever come out of it. But with all the three features in

place, evolution is unavoidable. In order to testify that the design process is

an evolving system in the Darwinian sense, we should identify all the three

features present in all the processes of architectural design. In addition to

this, to be a true Darwinian process of evolution, variations should be

produced at random. As Derek Gatherer has remarked, in design the consequence

of this theoretical position is that our ideas are not produced at will (as a

conscious effort) but are generated in our brain in an arbitrary way.

Brainstorming is based on this assumption: in a free flowing

session ideas should be produced from the subconsciousness in an associative

way in reaction of what someone else has suggested before, but without exerting

any criticism at all (variation at random).

These criticism should be applied afterwards and will than result in the

choice of valuable ideas (first selection of the ‘environment’ within the

brain). Brainstorming is a formalized way of what our brains are doing all the

time: extracting ideas (memes) from our communal meme pool in a haphazard

manner, associating them in an uncontroled way amongst one another, making

quick mutations and recombinations in a arbitrary fashion and then exerting

selective pressures for the first time (in the brain) and perhaps in a half

conscious way only.

If it is possible however to introduce deliberately variation or differences in these mental

processes, we will have a Lamarkian process of instruction at work instead of a

process of selection. With genetic engineering we have knowingly introduced

this instruction approach in biology. In designing, it might be practiced from

the beginnings of all design activities by human beings: this is the prevailing and counteracting hypothesis of the Darwinian

position. Just as the sense of design in nature happens to be an illusion

produced by selection, deliberate instruction in producing novel memes (ideas)

seems to be an illusion triggered by

selection.

As mentioned above, the actual theory of cultural

evolutionism is already elaborated by Derek Gatherer for the technical design

world. Gatherer’s theory is based on ‘Universal

Darwinism’ as concocted by Dawkins (1983). He asked himself if there could

be an other kind of Darwinian replicator on earth, ‘even now staring us in the face?’ Something like a gene, but

operating within a cultural instead of a natural environment. There the ‘meme’

(Dawkins, 1976) came in as an analogy of the gene. In genes heritability,

variability and selections occurs and as such satisfy the criteria needed to

identify them as replicators of a real Darwinistic evolving system. If memes

could satisfy the same conditions, a second type of replicator will be

discovered, functioning according to the same Darwinian rules of evolution.

But what is a meme? A lot of authors about memetics have

tried to formulate all-embracing definitions, but as Susan Blackmore (1999) has

commented after an extensive search none were sufficient enough to include all

the cases where the concept of a meme could be applied reasonably well. To take

her point of view: we should for the time being ‘keep things as simple as possible’. We should provisionally ‘use the term ‘meme’ indiscriminately to refer to memetic information in any of

its many forms; including ideas, the brain structures that instantiate those

ideas, the behaviours these brain structures produce, and their versions in

books, recipes, maps and written music. As long as that information can be

copied by a process we may broadly call ‘imitation’, than it counts as a meme.’

Derek Gatherer (1999) writing in the context of the design

of motor cars has compared a design meme with a ‘mental blueprint’: ...

‘abstract notions of form’ ... ‘first created in the minds of the

designers, and then used as templates from which the physical form of the motor

car was constructed. The mental concept was thus expressed in physical terms’.

Mental blueprints are what design researchers call declarative knowledge as

opposed to procedural knowledge. Declarative knowledge in the design fields is

about things (like buildings, spaces, lighting), their attributes (like form,

function, attractiveness) and the relations between them (like branched,

semilattice, network). Procedural knowledge on the other hand is about actions

and plans of actions (like how to analyse, sketch or design). It could relegate

among others to strategies and tactics of designing (knowledge about how to do

or create things). Both types of knowledge are used by designers and memes

could consequently be declarative as well as procedural, tracing the memetic

conceptualisation back to the broad

outline given by Susan Blackmore. In the results I will present some

distinctions made by me and the students to differentiate between certain types

of design memes.

Method

If the theory is right, we should find in every

(architectural) design process both: design memes and processes of retention,

variation and selection exerted on those memes. The detection might be

performed first in coarse and exploratory studies and (if the results are

positive) afterwards in more finetuned and affirmative investigations.

In a first run-up study the detection might be performed

indirectly like Gatherer has done by literature searching for appropriate

traces of the mentioned heredity, variation and selection in the design

processes described. A disadvantage of this approach is that you are dependent

on what others have noticed occasionally for often quite other reasons and

objectives.

A more direct and fast approach is to ask to reconstruct

their own design processes from long term memory with the aid of their

own remaining sketches, annotations, drawings, cardboard and computer models,

etc.This still exploratory approach is choosen here, because the possibility

existed to do it with a lot of students and a variety of design projects from

several years of design studio work, and because the effort needed was modest

and the results instructive in a preliminary phase to decide the next steps of

investigation.

In other studies we have used a logbook based system of

investigation. This is a more affirmative and time consuming manner in which

the designers are asked to fill in a logbook with their remarks immediately

after the end of their design sessions. This might be done in a free format

like in in-depth interviews, or for an easy transcription with standard

questions, to be filled in. The questions might be put forward directly about

what he or she has done and thought of about design things and related other

ideas and the role played by retention, variation and selection in those design

activities. Posed indirectly the questionaire

might ask about what he or she has done, how it was done and why.

One of the most detailed but also most

time consuming approaches is by protocol studies where the designer

is observed and videotaped in the act of designing and talking aloud about what

he or she is simultaneously sketching, perceptually discovering in the sketch,

thinking and deciding upon. The results can be analysed in minute details in

order to detect, determine and affirm the presence or absence of the looked

after memes and processes of retention, variation and selection at work. With

the low cost digital video editing posibilities now available, it is much

easier nowadays to perform this type of analysis.

The reconstruction method used was carried out with around

hundred 4th years architectural design students. They got handouts and copies

from publications explaining the theory of Darwinian (and Universal Darwinian)

evolutions and the possible role of memes for the cultural world (which

includes the technical and architectural design worlds as well). I asked the

students to reconstruct (two or) three of their finished design projects,

leaving the selection to themselfs, but asking to motivate their choices. The

reconstruction should be done from their long term memory, assisted by the

remnants of their design projects selected. The results should be reported in

an essay about ‘memetics in architectural design’. Failures in detecting memes

or processes of retention, variation and selection in their design work were

even more interesting and would be equally well excepted and graded if argued

in the same manner as those positively reporting on the same topics.

To facilitate their

work, I suggested to fill in a ‘project-process-matrix’ (figure 1)

with (a) in the rows the three projects, (b) in the columns the three processes

of retention, variation and selection and (c) in the cells the memes

encountered eventually.

|

|

HEREDITY |

VARIATION |

SELECTION |

|

Project 1 |

• Situation, program, concepual ideas and rules related. • Good and bad examples from publications and excursions

and mistakes from failed projects. |

• By mutation and (re)combination of heredity elements. • Incremental modifications of preselected concept. • Rules application. |

• By

comparisons between options or work

of others. • By

judgements of teachers, design critics, fellow students and own esthetic and

other preferences. |

|

Project 2 |

|

|

|

|

Project 3 |

|

|

|

Figure 1: suggested Project-Proces

Reconstruction Matrix

I encouraged them to hand in their provisional results in

order to get answers about upcoming questions and to secure some confirmation

or assurance for their approach. I made (and distributed) a summary about the

most frequently asked questions and upcoming themes and topics.

Results

The students did not have encountered much trouble in

completing the cells of the ‘project-process-matrix’ with appropriate memes.

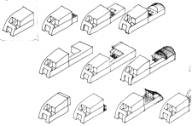

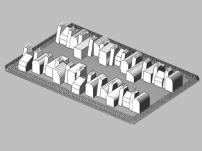

Both verbal and visual memes were quoted, indicated or reported. Most memes,

whether visual or oral ones were named or described in titels and sentences.

Some students refered to visual memes with names in the cells of the matrix and

documented them with drawings and computer renderings in separate

additions. Others made depictions

straight in the matrix cells in either thumbnail design sketches or

equivalently scaled down drawings or 3D perspectives of computer generated

models (figure 2).

Often, the terms used were clarified in subsection texts. To

reflect the phases of a ‘project-design-process’, some students appended an

extra left column with the number and phases involved (figure 3).

|

DESIGN PHASES |

HEREDITY |

VARIATION |

SELECTION |

|

01 Initiative 02 Feasibility 03 Projectdefinition 04 Brief/principles 05 Grids 06 Sketch Design 07 Analysis SD 08 Façade design 09 Preliminary Design 10 Analysis construct. 11 Options construct. 10 Stability calculation 11 Materials 12 Details 13 Final Design |

• Visual, verbal and text memes

about buildings, spaces and details. • All sorts of inspiration

patterns and diagrams and associations about objects like works of art,

landscapes, anatomical illustrations. • From libraries, lectures,

literature. • Comments from other students,

tutors or lecturers. |

• Spatial, architectural and/or

constructive options. • Variants about the building

site within landscapes, city areas and/or river banks. • 3D-models of human bodies and

buildings. • Ideas recombined from memory

and/or thinked up from own fantasy. |

• With given or own criteria. • About beauty, confort,

applicability, costs, effectiveness, efficiëncy, feasibility. • Adaptability to the site,

function, organisation. • Event and meaningfulness,

identity and orientation and perceptual liveliness. |

Figure 3: summarized example of some students output

(without specific contents of the design projects)

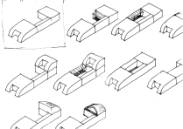

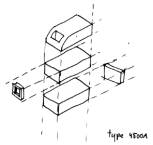

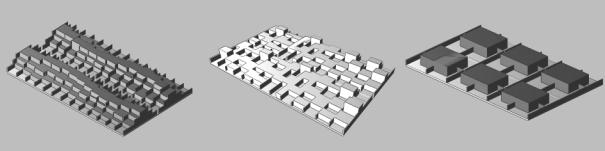

An illustrated version of this type of matrix is shown in

figure 4. The project illustrated was a design by the student Martin Koster as

part of a training job (architectural office of Marlies Rohmer, Amsterdam,

1999). The given meme was about ‘wild

housing’ (‘unregulated architecture’) for an exibition to be held in 2001

in Almere. The first inspiration meme were about a shed, which was transformed

(a) by a growth principle of mutations and combinations and (b) by ideas about

(1) chaos, (2) a common zone, (3) variants between separation walls, (4) a

field of patio housing and (5) terrace housing in blocks of four. The second

(and last) inspiration meme was about a boiler house.

Inspiration source: shed Given meme: Het Wilde Wonen (unregulated architecture) Design meme: expansion patterns Transformation-meme: groeien Inspiration meme : boilerhouse

MEME

SELECTION

variation

HEREDITY

MEME

SELECTION

VARIATION

HEREDITY

MEME

SELECTION

VARIATION

HEREDITY

Figure 4 :

Martin Koster for Architectenbureau Marlies

Rohmer

MEME

VARIATION

HEREDITY

SELECTION

MEME

VARIATION

HEREDITY

MEME

SELECTION

VARIATION

HEREDITY

SELECTION

SELECTION

VARIATION

HEREDITY

MEME

As an other alternative some students converted their phases

in a flowchart of heredity, variation and selection (figure 5).

|

|

INVERSED CONE DIVISION |

SPIRAL |

SPIRAL-ROOF |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

3 Divisions |

2 Divisions |

Undivided |

Propeller Rings Helix |

Heli-coidal roof |

Termi-nated under win-dow |

Flat roof |

FI- NAL RE- SULT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|||||||||

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(c) |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(a) |

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

The arrows in the matrix indicates where

some retention, variation or selection originates (in most cases the former

sketch design). Sketches with an (a), (b) or (c) denotes an selection made between them (either (a) continues or

(b) or (c); this is indicated by the arrows beneath the lowest X-crosses).

Figure 5: flowchart of heredity,

variation and selection phases, from student Wouter de Wit

In the retention or heredity cells ancestor

memes were identified by every student without any difficulty (figures

1-4). The refered memes happen to be

divided in situation, program, concept and rules regarding memes:

• Situation

memes were referred to in the sense of past starting conditions to be

taken into account as the heritage of the project involved or questions about

the building site of the given project.

• Program

related memes or issues were about prefered performance requirements or

the application of already testified performance effects.

• Conceptual

memes or ideas are about partial or whole architectural solutions.

Wholistic conceptual solutions refering to typologies like functional ones

(schools, shops, offices) or structural examplars (towerblocks, rows,

courtbuildings) or precedences as formative ideas, spatial organisational

concepts and partis of architectural buildings.

• Rules

related memes are discernable in sayings like ‘function follows form’

or ‘less is a bore’ or other heuristic search and decision rules mentioned by

the students as inheritable principles to steer their design activities.

If famous architects are mentioned they

might refer to one or a mixture of situation, program, concept and/or rules related memes as used or associated to

those architecs and worthy to be copied. Visions

of teachers, design critics or the students themselves might also be composed

from a combination of situation, program, concept and/or rules to be applied for deciding what to use

and what to avoid in copying for their own project design processes. Good as

well as bad examples from past and

present times were important. Some students especially noted mistakes from a failed project in order to dodge imitation and

replication deliberately.

Some information

came firsthand from reality as it was observed on excursions, trips or outings and eventually documented with

photographs, sketches and pictures or maps and leaflets and so on. But most

useful suggestions came from teachers or fellow students with tips to look in

some books or textbooks, to some

specific manuals or volumes, periodicals or magazines, journals or newspapers.

In the variation or differences cells

students had different experiences and opinions. They reported either a lot of

variety, no variety at all or something in between. The subject matter of

variety were shapes of buildings, part of buildings or details. Some

differences were reported about rooms, the configuration of spaces, the

composition of façades or building masses. Variety was also mentioned about

building materials, construction systems, the building site or surroundings and

so on. In most cases the students did not remembered how and when exactly they

got the idea to vary something.

Much variety was obtained by modifying or by mutation and combination from the

retention or heredity memes already acquired about the situation, program,

concept and/or rules.In the end this is

leading to some unity in all

that variety (unity in variety).

But perhaps most students focused very fast to one basic

design and reported their incremental

modifications afterwards made to adapt their design to all incoming or

already obtained considerations. As a result variety was obtained out of unity

(variety in unity).

Some students however observed the absence of variety in one

of their particular projects. For instance because the decisions were

transfered to some piece of music and then the melody was translated in

geometric compositions and measures by deductive rules of transcription. But in

this case indepth questioning reveiled necessary decisions remained to be taken

outside the automatically applied rules

of musical/geometrical compositions and measures: decisions producing variety

for comparison and choice.

Last but not least some noticed variation and differences

obtained in specially organised teamwork design courses or by way of their

participation to an architectural competition. Remarkable is, that no student

until now reported about errors, luck,

chance, coincidences or incidental occurrences as sources of variation.

In the Selection or preferences cells the

students had some difficulty to identify their selection phases, because

decisions about preferences were made continuously and it even started before

memes were allowed by them to enter as

ancestor memes. Some decided to mark the formal period of the in between design

studio presentation as their most important selection phase. Most selections

were made by checking once again the retention memes about the situation,

program, concept and/or rules, but now checked and compared to the actual

ruling conditions as it is infered from all the incoming information up to

then. Selections were made by comparisons between alternatives amongst one

another, compared to the program and site or compared to the work of other

students or existing buildings. Important were also the judgements from

teachers, visiting design critics or fellow students as wel as their own

esthetic preferences and considerations. The beauty of the solution was

mentioned as wel as performance criteria like about light and shadow effects,

transparancy, resistance against vandalism, continuity of the flowing of

spaces, building physics, construction, transport, assembly, styling,

governmental codes and regulations, the budget, judgments of authorities like

teachers and so on.

In general the exercision of retention, variation and

selection is conditional for the success of memes. But then, is for instance a

performance criterium not succesful in designing because it does not change as

a consequence of the design process? The performance criterium is often

imitated as well from one design

process to another with some retention of the gist of what is required, but

perhaps undergoing some adjustments and thus with variation creeping in and then

decided upon what to select. In other words, we should differentiate the memes

involved in the design process if we want to see sharper what is going on in

memetic terms.

The following differentiation (figure 6) appeared to be

useful and is based on the simpel sequence of input, transformation and output.

Figure 6: types of design memes

Input memes are those predestined to be transformed in output memes. Transformation memes are those

undergoing some manipulation like the recombination with other memes. Output

memes are the modified or adapted memes of the design solution. To transform an

input in an output however contextual requirements, governmental regulations

and so on should be known and taken into account without trying to chance those

type of environmental information: another type and group of intervening design

memes. To transform input to output designers are needed and consultants,

computers and other resources, showing another group of design related

(vehicles of) memes.

Dependent of the circumstances other words might be needed,

so input, throughput and output memes should be called different if necessary

within the objectives or context one is attending (figure 7):

•

the

input

memes might occasionally be

called ‘given’ memes, ‘problem’ meme, ‘inspiration’ meme, ‘old’ or ‘existing’

meme, ‘ancestor’, ‘elder’, ‘progenitor’, ‘forebear’ or ‘forefather’ meme.

•

the

transformation

memes might be differentiate in for instance in ‘design’ meme,

‘variety’ meme, ‘throughput’ or ‘change’ meme.

•

the

output

memes might be distinguished in new meme, solution memes, transformed

memes, descendant or offspring memes.

•

the

contextual

memes might be tell apart in selection meme, influencing or

environmental meme, steering meme and control meme.

•

the

resource

or help memes might be separated in editing and instrumental memes and production memes as call memes to be

processed somewhere else (like the execution of a rendering program).

Input memes that get transformed and exported as output

might be named lucky or success memes,

those that failed to be exported are failure or flop memes.

figure 7: vocabulary of design memes

The approach taken in this exploratory study is very gross.

The projects taken for consideration were from months to a few years ago and

should be reconstructed from long term memory with the aid of what is left of

filed away documentation.

Transmission, variation and selection in designing however

takes place at least on four levels (figure 8):

•

micro

level, where

the design activity is concealed in the individual brain. Such an activity

consist of memetic inheritance, at random generation of variety and subsequent

selection. It takes place mentally in milliseconds. It is on this mental level

that protocol research is aimed at.

•

meso

level, where

we can see someone doing things like spending time in the library consulting

journals, books and so on (transmission), like doing some sketching (variation)

or talking with someone involved in the decision making process like the

teacher, critic or the client involved (selection). All those activities takes

up multiples of quarter hours to hours.

•

macro

level, where

the activities are planned on weekly and montly intervals. There we become

aware of another rhythm of transmission (problem statement and documentation at

the beginning of the project), variation (designing and coaching on a weekly

basis) and selection (again on a weekly basis, halfway the project after some

weeks time and at the end after two or more months).

•

super

macro level,

where the personal development from successive design projects where identified

and elaborated. Where for instance in earlier work form as such was a goal,

while in later design projects form appeared only as a means to obtain other

goals.

This study was intended to deal with the macro level, but

the students often tried very succesfully to analyse their design project work

on the other levels as well, because they feeled that those levels were most

significant for designing.

1. oldest inner

cerebral cortex, centre of emotions and subconsciousness, artistic and reflex

behaviour, pragmatics; 2. middle cortext, centre of the senses and

preconsciousness, technical and sensomotoric behaviour, syntagmatics; 3. newest

outer cortex, centre of logical reasoning and consciousness, scientific and

inferential behaviour, paradigmatics.

Figure 8: four levels of design studies

Conclusions

As put forward in the introduction, the central question we

wanted to answer was about the possibility of application of Darwinistic

evolutionary theory from biology to architectural design. The answers of the

students makes it highly probable to answer the question positively. The

students were unanimous about the occurrence of memes in their design

activities. They could name and depict memes appropriate in their processes of

heredity, variation and selection. They could even imagine, detect and

acknowledge the functioning of brainstorming effects in the arbitrary

production of novel ideas or memes, but were still confused with the

consequences of their own findings. The appearing autonomy of the

(architectural) designer is then at stake with all the accompanying ingenious

creativity and originality that brought along.

Philosophical remarks were also made about the applicability

of the theory. Like history, linguistics or bicycle riding, no one expected to

design (or decide, write or ride) better by understanding how those processes

take place. But despite those limitations, they appreciated the exercise to

understand better there own design behavior and development over the years.

Nevertheless knowledge about the mechanisms behind those processes are

essential if we want to simulate them for fun or training like in computer

games and simulators or to explore the (self-defined) available design spaces

in morphogenetic design programs.

What remain to be done is at least to look with closer

attention to the evolution of usual architectural design projects. Obviously,

the theory needs some adjustments because designing turned out to be a not

outspoken population based activity. Students do not design by breeding whole

populations of designs and subsequently do not select among them in order to

allow the survivals to breed again and again until some optimised or

compromised solution will emergence in the end. This corresponds to the so called

breadth first strategy, which is hardly applied in architectural design. There,

the so called depth first strategy is nearly always used, exploring and

developing only one (or a few) alternatives at a time until eventually

something important forces the designer to abandon the looked for solution and

start anew. But if we take a look from the meme’s eye view like most of the

students did, we have already experienced something quite different. From this

a lot of questions are left behind to be investigated.

A last but not least issue is about artistic design.

Although memetics claims to explain all culture, the memetics of engineering is

according to Gatherer ‘certainly more

approachable than the memetics of art.’ Architecture is something in

between and might serves as a bridge between the two. The results up to now are

encouraging, but detailed analysis of the artistic elements in the design work

of the architectural students (and of artists and architects in practice)

remain to be done.

References

Blackmore, Susan: The

Meme Machine, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999

Darwin, Charles: The

Origin of Species, Penguin, London 1985 (reprint of 1st edition, 1859).

Dawkins, Richard: The

Selfish Gene, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1976.

Dawkins, Richard: Universal Darwinism, in Bendall, D.S.

(ed.), Evolution from Molecules to Men,

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1983.

Gatherer Derek: The Memetics of Design, in Bentley, P.J.

(ed.), Evolutionary Design by Computers,

1999.

Steadman, Philip: The

Evolution of Design, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1979.