How I Drew One of My Pictures: *

or, The

Authorship of Generative Art

Adrian Ward BSc & Geoff

Cox MA(RCA)

Sidestream, London &

CAiiA-STAR, School of Computing, University of Plymouth, UK

e-mail: adrian@signwave.co.uk &

geoffcox@excite.com

Abstract

The concept of value is

traditionally bestowed on a work of art when it is seen to be unique and

irreproducible, thereby granting it authenticity. Think of a famous painting:

only the original canvas commands genuinely high prices.

Digital artwork is not valued

in the same way. It can be copied infinitely and there is therefore a

corresponding crisis of value. It has been argued that under these conditions

of the dematerialised artwork, it is process that becomes valued. In this way,

the process of creation and creativity is valued in place of authenticity,

undermining conventional notions of authorship.

It is possible to correlate

many of these creative processes into instructions. However, to give precise

instructions on the construction of a creative work is a complex, authentic and

intricate process equivalent to conventional creative work (and is therefore

not simply a question of 'the death of the author'). This paper argues that to

create ‘generative’ systems is a rigorous and intricate procedure; to have a

machine write poetry for ten years would not generate creative music, but the

process of getting the machine to do so would certainly register an advanced

form of creativity. Moreover, the output from generative systems should not be

valued simply as an endless, infinite series of resources but as a system.

When a programmer develops a

generative system, they are engaged in a creative act. Programming is no less

an artform than painting is a technical process. By analogy, the mathematical

value pi can be approximated as 3.14159265, but a more thorough and accurate

version can be stored as the formula used to calculate it. In the same way, it

is more complete to express creativity formulated as code, which can then be

executed to produce the results we desire. Rather like using Leibnitz's set of

symbols to represent a mathematical formula, artists can now choose to

represent creativity as computer programs (Harold Cohen’s Aaron, a computer program that creates drawings is a case in

point).

By programming computers to

undertake creative instructions, this paper will argue that more expansive

traces of creativity are being developed that suitably merge artistic

subjectivity with technical form. It is no longer necessary to be able to

render art as a final tangible medium, but instead it is more desirable to

program computers to be creative by proxy.

[The paper

refers to Autoshop software,

available from http://autoshop.signwave.co.uk]

Authorship

Traditionally, the

concept of value is bestowed on a work of art when it is seen to be unique and

irreproducible, thereby making it authentic and granting it 'aura'.[1] More

recently, emergent technical possibilities emphasise processes of creation and

creativity in an age of infinite reproducibility. Therefore, through

reproduction, this lack of aura accounts for the emancipation of the artist

from the religiose mythologies of creativity, authenticity and authority.

Although the

‘author-god’ might be dead (according to Post-Structuralist theory), we are

forced to accept this ‘death’ as an inability to claim the privileged source of

meaning or value of a work of art and artist.[2] This is by no means

new; there are numerous precedents for collaborative experimentation in

creativity and automatism within a history of art-machines, robotics, and

deferred authorship: the use of chance by dadaists, and automatism by

surrealists, aimed to stimulate spontaneous and collective creative activity

and to diminish the significance of the artist. As the creating subject or

author has largely been discredited and dematerialised over the years, there is

a pressing need to examine new demarcations, and the functions released by this

disappearance.[3] Perhaps ‘the death of

the author’ is simply too literal, (too obvious and final) a metaphor to offer

a critique of the productive apparatus by which contemporary creative

operations using computers are organised and regulated.

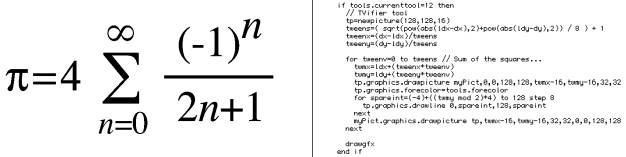

Fig. 1.

The mathematical

value ‘pi’ can be approximated as 3.141592, but a more thorough and accurate

version can be stored as the formula used to calculate it. By analogy, it is

more precise to express creativity formulated as code, which can then be

executed to produce the desired results. Rather

like using

Leibnitz's set of symbols to represent a mathematical formula, creative work

can now be expressed as computer programming (itself necessarily mathematical,

a creative practice in itself). Programming is no less a potential artform than

painting is simply a result of technical procedures (even paintings are

‘readymades’ according to Duchamp, as they use ‘found’ manufactured materials

as a result of commodity production). Under the conditions of the

dematerialised artwork, it is no longer necessary or even desirable to be able

to render art as a final material object or dead-end commodity; it is as if

process and code is now rendered as the material artwork.

Execution

When a programmer develops a generative system, they are clearly

engaged in a creative act but what kind of process is being executed? An artist

makes creative decisions to produce a final artwork, yet it would be futile if

these decisions were the same every time. In this sense, the focus of creating

generative art is not trying to achieve a balanced output, but to capture these

decisions as logical structures. The computer executes these rules but never

produces the same result twice. In this sense, the code could be seen to be

more like the chaos mathematics used to simulate complex systems than a

mathematical formula like pi. Ironically, perhaps this idea of unique execution

could be seen to re-establish aura, yet the decisions the code takes to arrive

at a final result are of little significance (as in the case of a random number

generator, for example). Perhaps the lack of aura is maintained all the same.

When a programmer develops a generative system, they are clearly

engaged in a creative act but what kind of process is being executed? An artist

makes creative decisions to produce a final artwork, yet it would be futile if

these decisions were the same every time. In this sense, the focus of creating

generative art is not trying to achieve a balanced output, but to capture these

decisions as logical structures. The computer executes these rules but never

produces the same result twice. In this sense, the code could be seen to be

more like the chaos mathematics used to simulate complex systems than a

mathematical formula like pi. Ironically, perhaps this idea of unique execution

could be seen to re-establish aura, yet the decisions the code takes to arrive

at a final result are of little significance (as in the case of a random number

generator, for example). Perhaps the lack of aura is maintained all the same.

![]() Creative decisions

are influenced by various indeterminable factors, and in this way creativity

cannot be simply reduced to a problem-solving activity or code that makes

decisions. A great deal of generative art appears to focus on giving the

computer some limited form of intelligence so that these decisions can be made,

either through the use of neural networks or reference-based systems. However,

a great deal of these so-called creative decisions made by artists are driven

by chance, or other imperceptible influences. Why attempt to capture a creative

action as a formal logical procedure, when in fact a random decision is often

more suitable? Throwing paint on a canvas is not governed by precise directions

of where the paint will go, but simply by the decision to do so. The decision

was made and the action was unpredictable. In the same way, code systems

undertake decisions, but the actual execution is (or can appear to be) random.

Creative decisions

are influenced by various indeterminable factors, and in this way creativity

cannot be simply reduced to a problem-solving activity or code that makes

decisions. A great deal of generative art appears to focus on giving the

computer some limited form of intelligence so that these decisions can be made,

either through the use of neural networks or reference-based systems. However,

a great deal of these so-called creative decisions made by artists are driven

by chance, or other imperceptible influences. Why attempt to capture a creative

action as a formal logical procedure, when in fact a random decision is often

more suitable? Throwing paint on a canvas is not governed by precise directions

of where the paint will go, but simply by the decision to do so. The decision

was made and the action was unpredictable. In the same way, code systems

undertake decisions, but the actual execution is (or can appear to be) random.

Generative creativity

Clearly the

production of generative systems through this precise execution of decisions

(and not actions) is a rigorous and intricate creative procedure. Moreover, the

output from generative systems should not be valued simply as an endless,

infinite series of resources but as a system - and not just any system, but a

social system. It is possible to resolve many creative processes into

instructions, but crucially according to Csikszentmihalyi: ‘... creativity does

not happen inside people's heads, but in the interaction between a person's

thoughts and a socio-cultural context’.[4] If this is the case, does the

computer programmer then, offer a radicalised art practice that reflexively

engages with the productive apparatus and social context? If so, this

surprisingly echoes what Walter Benjamin recommended in 1934 for radical art

practice:

‘An author who has

carefully thought about the conditions of production today... will never be

concerned with the products alone, but always, at the same time, with the means

of production. In other words, his [sic] products must possess an organising

function besides and before their character as finished works.’[5]

Both the

laboratories of art and science require reflexive work to fully comprehend

their processes. Invention and innovation is made possible by groups and

individuals operating necessarily within social systems and specific

discourses. By programming computers to undertake creative instructions, it is

possible to argue for more expansive traces of creativity that suitably merge

artistic subjectivity, social context with technical form. For instance, to

make a system more intelligent it needs to operate socially, as with a Neural

network that needs feedback in order to learn.

Emergent

creative practices have sought to examine creativity in the light of scientific

investigations in artificial life, simulating the characteristic processes of

living things, from the operations of ecosystems and evolution to the encoding

of DNA. Eduardo Kac’s Genesis,

commissioned by Ars Electronica 1999 is a striking example of this tendency.

The key element of the work is the reproduction of an ‘artist's gene’,

synthetically created by translating a sentence from the book of Genesis into Morse Code, and then

converting the Morse Code into DNA base pairs according to a conversion

principle specially developed for the work.[6]

One

consequence of this emerging field are wild claims exemplified by writers like

Kevin Kelly (in describing the work of artist Karl Sims) claiming: ‘The artist

becomes a god’.[7] It has to be remembered that the ‘death of the author’ (as

well as Nietzsche’s claim that ‘god is dead’) was a metaphor to site the

production of meaning in the act of viewing or reading; and so counter supplied

dogma of authoritarian communication and in the spirit of democratic politics,

in other words.[8] So any claim that meaning now lies in the code, or that

reality has collapsed into the code (to paraphrase Baudrillard out of context),

must be treated with a certain amount of scepticism. This is rather like the

biological reductionism of much of the debate about genetic engineering that

negates social processes.

Creativity has

become the engine for ‘cultural reproduction’ in the factories of Western

technoculture so caution is necessary.[9] Creativity has become a buzzword for

western governments who valorise their creative industries,[10] and continue to

mythologise individual practitioners for the benefit of ‘cultural capital’ and

the ‘free-market’ - which tautologically isn’t free at all. But these ‘false

gods’ or ideologies do not go unopposed, with active networks such the Free

Software Foundation promoting shared ‘open source’ code, collective authorship

and the legal protection of free distribution.[11] Moreover, it is significant to note that

this year’s (1999) Ars Electronica Golden Nica award (for ‘net.art’) was

awarded not to an individual artist but to the Linux operating system, the operating system of choice for the Free

Software Foundation. Based on a set of false principles, some ‘hackers’ have taken Richard Stallman, founder of

the Free Software Foundation, and/or Linus Torvalds, the creator of Linux as god-like. It is interesting to

note that people are eager to attribute religious properties to key figures in

movements that question traditional notions of authorship and creativity.

Addressing this issue, Danny O'Brien explains that ‘when we don't understand

the motivations of others, religion stands first in line to explain’.[12] The

spontaneous and irrational actions of the creative human subject seem to be

neatly explained in the dogma that ‘art is a gift from the gods’.[13]

Autonomy

The core of human creativity is notoriously difficult to define, as an individual and social phenomena. These cultural anxieties are expressed in many forms including intellectual property, from the patenting of software code to human genes.[14] It is somewhat ironic to note that both machines and humans are more or less programmed, but not through ‘natural’ causes but cultural determinants. This is a recognition that subjectivity is determined by other destabilising forces and that creative-subjectivity itself is socially encoded. Echoing one definition of subjectivity that lays emphasis on discursive frameworks, the artist is revealed to be a rhetorical invention operating in much the same way as a coded machine that follows a crude rule-based system, auto-generating what already exists. If the artist has always been ‘automated’ to some extent, this offers the opportunity to mount a critique of autonomy as much as creativity. The point here is not to build artificial intelligence or life but to question the artificiality of its deployment in creative endeavours (or something along those lines).

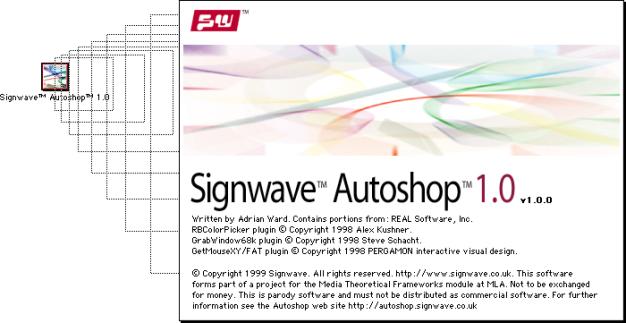

Fig. 3.

Many generative

systems rely upon creating autonomous systems which can, to a limited degree,

be aware of their surroundings, and therefore respond to their environment. The

basic notion is that it applies logic it has learnt of the outside world to

whatever input is given, causing new reactions which can be captured as

creative output. However, trying to imitate art by imitating life is an

unnecessary confusion. In this respect, Autoshop

makes no attempt to be autonomous. It truly is a mechanic reproduction of creative

decision-making, and so avoids the issue of ‘artificial intelligence’. If a

non-artificial intelligence system can still be seen to be creative (because

the code is merely an extension of the artist’s own logic) then there is no

need to deploy artificial intelligence, as the artist already possesses

intelligence (or not, as the case may be).

Creative agency

The creative

subject has been traditionally viewed as possessing quite distinct cognitive

and mechanical processes with other workers or machines playing a secondary

subservient role. This has clearly changed but the auto-generative art-machine

relies on its code, and as much as generating a deferral of authorship is still

encoded and authored in itself. Yet, as Haraway says: ‘it is not clear who makes

and who is made in the relation between human and machine. It is not clear what

is mind and what is body in machines that resolve into coding practices.’[15]

Former firm distinctions between biology, technology and code, are now

unreliable, and under these changing conditions it is the issue of autonomy

(rather than creativity) that appears most pressing. Both the social practices

of science and art serve to establish myths of autonomy. Indeed, where does

generative art generate from and under what conditions? There is a danger of

excluding the possibility of the human subject as a potential agent of change

in these scenarios.

If both humans and machines are conceived as coded devices, the computer programmer works in a tradition of a bricoleur in the assemblage and hacking of code, rearranging its structural elements. Coding is the ability to make judgements and render those as logic; for programming has always been about solving problems using logic. If we could resolve our creative impulses as series of logical decisions, we could code them. Yet, subjectivity is embedded in the social system like code itself. Its manipulation therefore is crucial to effective programming and an understanding of ideological processes.

Fig. 4.

Numerous so-called

creative works play with ideas of randomness, but it is intention and purpose

that are crucial (in this way, the truism of monkeys with typewriters

eventually coming up with the complete works of Shakespeare misses the point).

Rather, Autoshop uses irony to

articulate some of the expectations of commercially-available software and the

limits of its functionality. Without this strategy, there is a danger here of

irony merely perpetuating what it wishes to critique; in other words parody

falling into pastiche. It purposefully breaks the logical sequence of

prediction and consequence: if such and such, then do the following or

something else. Extending this, one can make a compelling argument that Autoshop should only be appreciated as

software, its output irrelevant. With this in mind, it is proposed that the

next version of the software might ‘patch’ a bug so there is no ‘Save As’

feature at all. What this serves to emphasise is that creativity lies not in

the modification of rules, but in setting the criteria for the rules, rather

like conceptual art. Oddly, much ‘neo-conceptualism’ manages to avoid having a

concept.

Practices that

insist on separating form and function operate impoverished theories of

representation. Creativity lies somewhere in the link between the act of

representation and conceptual clarity. An automated programme might use its

representational strategies but it has no concept in itself. This paper argues

that responsibility for the concept as well as the criteria for the rules and

code, remains in the domain of the author.

References

·

The title of the paper is taken from Italo Calvino’s ‘How I Wrote

One of My Books’, Bibliotheque Oulipienne

No. 20, in Raymond Queneau et al, Oulipo

Laboratory, Altas 1995, explaining the formulation of structure in If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller,

Secker & Warburg, 1981. In turn, his title echoes Raymond Roussel’s Comment j’ai écrit certains de mes livres

Lemerre, 1935.

[1]

This is a reference to Walter Benjamin’s famous essay ‘The Artwork in the Age

of its Technical Reproducibility’ (written in 1935/36), in Illuminations, London: Fontana 1992.

[2] Roland

Barthes, ‘The Death of the Author’ in Image-Music-Text,

London: Penguin 1982, p.146.

[3] This is paraphrasing

Foucault, who writes: ‘Rather we should re-examine the empty space left by the

author’s disappearance; we should attentively examine, along its gaps and fault

lines, its new demarcations, and the reapportionment of this void; we should

await the fluid functions released by this disappearance.’ Michel Foucault,

‘What is an Author?’, in, Bouchard, ed., Language,

Counter-Memory, Practice, p.128. On the removal of the Author, Barthes

says: ‘(... the text is henceforth made and read in such a way that at all

levels the Author is absent).... The Author, when believed in, is always

conceived of as the past of his own book: book and author stand automatically

on a single line divided into a before

and after.’ Barthes, op cit.,p.145.

Furthermore, it has become a postmodern truism to state that ‘... the artist

invents nothing, that he or she only uses, manipulates, displaces,

reformulates, repositions what history has provided.’ Douglas Crimp, On the Museum’s Ruins, MIT Press p.71.

[4] Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of

Discovery and Invention, Harper Collins Publishers: New York 1996.

[5]

Walter Benjamin, ‘The Author as Producer’, in Understanding Brecht, London: Verso 1992, p.98; first presented in 1934, at the institute for the study of

Fascism, Paris; Benjamin argues that social relations are determined by the

relations of production and therefore progressive artists should try to

transform those relations. Note: a popular alternative view to describe

this is as a return to artisanship.

[6] Details on what Eduardo Kac calls

‘transgenic’ works can be found at http://www.ekac.org/transgenicindex.html

Kac’s Genesis

was commissioned by Ars Electronica 1999 and presented online and at the O.K.

Center for Contemporary Art, Linz, from September 4 to 19, 1999. Also see,

‘Transgenic Art’, first published in Leonardo

Electronic, Volume 6, Number 11, 1998.

[7] Kevin Kelly, ‘Genetic images’, in Wired, 2.09.

http://www.wired.com/wired/2.09/features/sims.html, 26 August 1998. See also, Out of Control for more speculation.

[8] Barthes famously claimed

‘... the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the Author’, Ibid., p.148.

[9] This refers to Pierre Bourdieu’s use

of the term ‘Reproduction’ that connects cultural phenomena firmly to the

structural characteristics of a society, and shows how the culture produced by

this structure in turn helps to maintain it, in Pierre Bourdieu, Jean-Claude

Passeron, Richard Nice, Tom Bottomore, Reproduction

in Education, Society and Culture, London: Sage 1990.

[10] Tony Blair, the UK Prime Minister is

quoted as having said that ‘I believe we are now in the middle of a second

revolution, defined in part by new information technology, but also by creativity’

and estimated to be worth £50 billion to the economy, in The Guardian newspaper, 22 July 1997.

[11] For more information, the Free

Software Foundation’s website is http://www.fsf.org/

[12] Danny O'Brien, ‘Some Past and Future Clichés Regarding Linux’

in Mute Magazine, Issue 12, 1999.

[13] Andre Spierings, ‘You can't spell

artifice without A-R-T’, http://hyperreal.webjump.com

also, ‘The Autonomous Artist

in Theory and Practice’ http://home.internex.net.au/~omgang/auto/TheAutonomusArtist.html (sic)

[14]

The Guardian newspaper’s headline of

25 October 1999 carried the story that a US biotechnology company (Celera) was

seeking to patent segments of the human genetic code. This goes against the

British-led efforts to negotiate an Anglo-American accord to ban patents; to

publish the code for each gene within 24 hours of its discovery (rather like

the principles of ‘Open source’) thus making it freely available to the benefit

of the world-wide scientific community as a whole (e.g. to tackle diseases and

so on). In patent law, discoveries in nature are not seen as inventions; the

counterclaim is that discoveries should be subject to intellectual property

rights.

[15] Donna Haraway, ‘A Manifesto for

Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s’, in Linda

Nicholson, ed. Feminism/Postmodernism,

London: Routledge 1990, p.219.

Figures

1. How to calculate p (pi), how to

apply a graphic effect to a bitmap.

2.

Toolbar from Autoshop

3. Progress

indicator shown during ‘Autopilot Creativity’ in Autoshop.

4. Opening

the Autoshop application.