Music Composition with Interactive

Evolutionary Computation

Nao Tokui.

Department

of Information and Communication Engineering,

Graduate

School of Engineering, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan.

e-mail: tokui@miv.t.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Prof. Hitoshi Iba.

Department of Frontier Informatics, Graduate School of Frontier

Sciences,

The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan.

e-mail: iba@miv.t.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Abstract

The interactive evolutionary computation (IEC),

i.e., an evolutionary computation whose fitness function is provided by users,

has been applied to aesthetic areas, such as art, design and music. We cannot

always define fitness functions explicitly in these areas. With IEC, however,

the user's implicit preference can be embedded into the optimization system.

This paper describes a new approach to the music

composition, more precisely the composition of rhythms, by means of IEC. The

main feature of our method is to combine genetic algorithms (GA) and genetic

programming (GP). In our system, GA individuals represent short pieces of

rhythmic patterns, while GP individuals express how these patterns are arranged

in terms of their functions. Both populations are evolved interactively through

the user's evaluation. The integration of interactive GA and GP makes it

possible to search for musical structures effectively in the vast search space.

In this paper, we describe how our proposed method generates attractive musical

rhythms successfully.

1.

Introduction

We have been developing an interactive system

called “”CONGA” (the abbreviation of “composition in genetic

approach” and also the name of an African percussion), which enables

users to evolve rhythmic patterns with an evolutionary computation technique

[10].

In general, evolutionary computation (EC) has

been applied to a wide range of musical problems, such as musical cognition and

sound synthesis. Among such problems, composition is one of the most typical

and challenging tasks. Music composition can be taken as a combinatorial

optimization in the infinite combination of melodies, harmonies and rhythms.

Thus it is natural to apply computational search technique as typified by EC. Up to now, Genetic algorithms (GA) [4] and genetic programming

(GP) [9] have been successfully applied to the music composition tasks [1]. For example,

Biles used GA to generate jazz solo [7] and Johanson and Poli generated

melodies by means of GP [2].

When these EC techniques are EC is applied to

the musical composition, there are three main topics to be considered [1],

i.e., the search domain, the genetic representation, and the fitness

evaluation.

The first topic is the search domain. As

mentioned earlier, the musical composition is a combinatorial optimization

problem, whose

search spaceion is basically unlimited, because

there is an infinite possible combinationscombination of

melodies, harmonies, and rhythms. It is not reasonable to expect computers to

compose music like Mozart or Beethoven from scratch. Therefore, the composition

must be guided by some constraints.

The next is the genetic code representation of

music. Generally speaking, the effectiveness of EC search largely depends on

how to represent a target task as a genetic code.

The third topic of consideration is the fitness

evaluation of EC individuals. Because music is evaluated based on the ambiguous

human subjectivity, it is difficult to define the explicit fitness function in

the musical composition.

From

these points of view, we

can describe our system as follows:Considering these requests, we establish our system

“CONGA”. The salient features of our system are as follows.

1.

Search domain: Musical rhythm patterns

The purpose of our system is to generate short

(i.e. from 4 to 16 measures) rhythm patterns. However we only deal with a

particular subset of rhythms. In the context of this paper, the word rhythm means a sequence of notes and

rests which occur on natural pulse subdivisions of a beat. This is a reasonable

reduction of the search domain for the application of ECs.

There are a few related works. in this direction. For

instance, Horowitz used an IEC to learn user’s criteria for evaluating

rhythms and succeeded in producing one-measure long rhythm patterns [3]. To

produce longer andmusically more interesting phrases musically, we have

adopted unique genetic representation described later.

2.

Genetic representation: Combination of

genetic algorithm and genetic programming.

Our system maintains both GA and GP populations

and represents music with the combination of individuals in both populations.

GA individuals represent short pieces of rhythmic patterns, while GP

individuals express how these patterns are arranged in terms of their

functions. In this way, we try to express a musical structure, such as a repetition,

with the structural

expression of GP and evolve longer and more complicated rhythm phrases

without spreading the search space.

3.

Fitness function: User him-/herself.

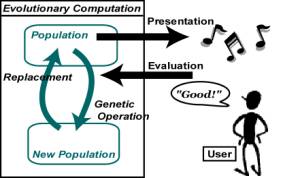

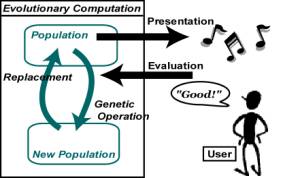

A common problem in applying EC to an aesthetic

task is the difficulty of setting up a formal fitness function to evaluate the

individuals. Interactive evolutionary

computation (IEC) avoids this problem by making human users evaluate each

individual empirically (see Fig.

1) [6].

In a conventional EC, each individual is

evaluated by a given fitness function. On the other hand, a user evaluates

individuals by him-/herself

in an IEC. Therefore IEC can make EC techniques applicable to subjective

optimization problems without explicitly modelling the human subjective

evaluation systems.

Some researches mentioned before adopted this

IEC technique for the musical composition [2,3,7]. In a similar way, our system

adopts the idea of interactive evolution, which enables to generate music on the basis of user’s criteria. We also implement the mechanisms to keep the

consistency of human subjective evaluation and the diversity of the genotypes.

However there is a major obstacle toThe common difficulty in

the practical use of IEC. It is the human fatigue. Since a

user must cooperatework with a tireless computer andto evaluate each individual

in every generation, he/she may well feel pain. It is the biggest remaining

problem to reduce the psychological burden on users. In order to deal withthis

problem, we proposethis, we adopt an evaluation assistance by

means of learning user’s criteria with a neural networkmethod.

The rest of the paper is

structured as follows.

Section

2 shows the overall image of our. Section 3 introduces the genetic

representation. Section 4 describes user’s

operation and the evaluation assistance by the system. Section 5 shows result of several

experiments, followed by some conclusion in Section 6.

Fig. 1 The framework of the interactive evolutionary computation.

2. System architecture

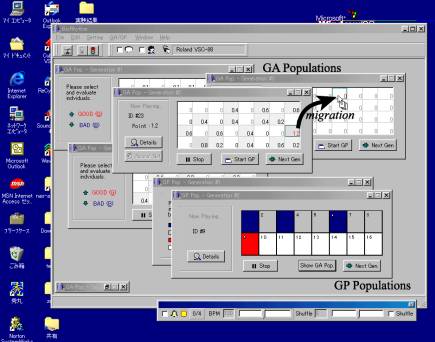

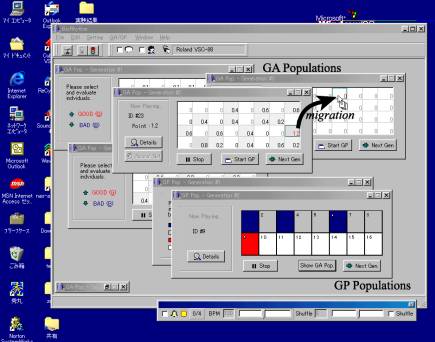

Fig.

2 gives an overview of our system. This system has been developed in

Windows PC environment with Borland C++ Builder. The system is based on MIDI

(Musical Instruments Digital Interface) specification. MIDI is a standard

interface between electronic instruments, such as synthesizers and samplers,

and computers. Maximum MIDI library [12] is used to embed MIDI compatibility.

As shown in Fig.

2, GA and GP populations are displayed as grids on windows respectively.

Each cell of the grid is associated with an individual in the correspondent population.

A user can listen to any individual by clicking the corresponding cells and

give a fitness value.

Fig.

3 shows the system architecture. Note that the genetic

representation in our system contains two populations. These are a population

of GA individuals, which represent short musical phrases, and a population of

GP individuals, which represent how these short patterns are arranged in time

line. The alternation of generations occurs in these two populations based on

the user’s given fitness values.

We have adopted “Multi-field user interface” [13], in which children are displayed

in a separate window instead of replacing their parents. In addition, we have

implemented the migration among these

windows. Users can migrate an individual from a display window to another by

the drag and drop operation. This feature provides more flexible breeding and

richer diversity of genotypes by the effects similar with the island model in GA or GP [5].

Moreover, we have enhanced the system

flexibility by introducing user-defined parameters. Users can set the

population sizes, input

the length of generated rhythm patterns and select timbres for

composition. Users also can set “swing

rate” of the rhythms. These features make generated phrases

much more musicalcontribute to generating much more musical phrases.

Besides this, the system can synchronize with other MIDI sequencers, by sending

MIDI time clock (MTC). If you program a melody with that external sequencer in

advance, you can evolve rhythm patterns, which sounds good with the

melody.

Fig. 2 The “CONGA”

system overview.

Fig. 3 The system architecture.

3. Genetic Representation

3.1. Genetic Algorithm

GA individuals represent short (i.e., a half or

one measure long) multi-voice rhythm patterns.

Genotype of GA individuals is a two-dimensional array of integers (Fig. 4). Users can set the number of timbres, the length

of the phrase represented by an individual and the unit time resolution, e.g., eighthnote

or sixteenth note. Thus user’sthe settings determineuser’s setting determines

the size of arrays. Each element of the array stands for the strength of the

beat. This value is called velocity

in the terminology of MIDI. VThe velocity is a number between 0 and 127,

because the velocityit is represented

as 4 bit datas.

We have introduced genetic operations listed in Table.1, assumconsidering that they are musically

meaningful operations.

Fig. 4 An example of GA individual.

Fig. 5 An example of GP individual.

Table.1 Genetic operation in GA.

|

Type

|

Name

|

Description

|

|

Crossover

|

One-point crossover

|

Apply standard

crossover

|

|

|

Part exchange

|

Exchange parts

for timbres among individuals

|

|

Mutation

|

Random

|

Apply standard

mutation

|

|

|

Rotation

|

Rotate the loci

a random amount

|

|

|

Reverse

|

Play the loci

in reverse order.

|

|

|

Timbre exchange

|

Exchange

timbres within an individual

|

3.2.

Genetic Programming

GP individuals represent how the above-mentioned GA individuals are

arranged in a time series. Terminal nodes are ID numbers of GA individuals in GA

population. Non-terminal nodes are functions, such as repetition

and reverse operations

(see Fig. 5, and Table.2).

We used normal genetic operations in GP, e.g.

sub-tree crossover and mutation. The GP engine is based on a revised version of

LGPC (Linear GP system in C) [11]. Linear GP is one of GP notations, in which

program structures are represented as a linear array. We have been developing

LGPC as a general-purpose Linear GP system and showed its advantage in the

speed and low memory consumption [11]. Adopting faster system can lighten the

burden imposed on users by shortening waiting time. AndMoreover the

feature of the low

memory consumption is effectivdesirable especially in common PCs, which usually

have restricted memory.

Although the above representation enables

structuring music sequence, the length of the expressed music may be problematic, i.e., the generated music can be all

different in their lengths. To deal with this problem,

we imposed a constraint upon the length in the

following way.

A new generation is bred with a larger

population size. Then, GP individuals are selected based on the length of the

phrase represented by the individual. Only individuals with lengths close to

the length given by the user in advance will be selected and displayed to the

user.

In this way, we can keep the constant length

of rhythm patterns represented by diverse GP individuals without

increasing individuals, which a user must face to evaluate.

Table.2 Functions in GP.

|

Name

|

Arity

|

Description

|

|

|

|

Sequence

|

2

|

Play NODE1 and NODE2 consecutively.

|

|

|

Repetition

|

2

|

Repeat NODE1 till the lengths of both child

nodes become the same.

|

|

|

Concatenation

|

2

|

Play the first half of child NODE1 and the

second half of NODE2 consecutively.

|

|

|

Reverse

|

1

|

Play NODE1 in reverse.

|

|

|

Random

|

0

|

Play randomly selected node.

|

|

4. Evaluation and Alternation of generations

4.1. User’s operation

As we have

stated repeatedly, the

EC selection isdone based

on the user's evaluation. Users listen to each individual and increase or

decrease the fitness value from the standard valueaccordingly. The

fitness values are normalized in the population and used in the selection

process. Selection method isWe use the

proportional selection with the elite strategy.

As we all know, hHuman subjective

evaluation is very ambiguous and inconsistent in general. This tendency can be strong,

especially when thetarget of evaluation target is music.

Unlike images, music cannot be displayed in parallel. Therefore our evaluation

can be largely affected by the presentation order.

To compensate for this defect, we set standard individuals

for the evaluation. To be concrete, if an individual is copied and reproduced

in a generation, its fitness value is also copied from the value, which user

gavea

user has given in the previous generation. The user can evaluate other individuals

more consistently with the reference to this standard fitness value.

In this system, GA and GP populations are

evolved separately. At first, the alternation of generations is done in GA

population several times. Next, GP individuals with evolved GA gene codes are

evaluated and the generation of GP population proceeds. If the user wants

better GA individuals for the GP evaluation, he/she can go back to the GA

population and evolve it again. This cycle continues until the satisfyinga satisfactory rhythm

evolves.

4.2. Evaluation Assistance

During the

above-mentioned operations, the psychological burden is

not negligible to the user who listens and gives a fitness value to each

individual. This load on users is a

common problem in the IEC technique. We canmay reduce the

population size or the

number of generations in order to lighten the burden. However,

the effectiveness of EC search maycan be degraded for that. Thus, we need to

solve this dilemma for the more widespread applications

of IEC.

For this purpose, we

have implemented the automatic evaluationan evaluation assistance

method. When generations proceed, we breed a larger number of

individuals. Subsequently, each individual is evaluated automatically with the

technique shown below.

1.

The reduction in GP individuals based on the length of represented

rhythm (see section 3.2).

2.

The reduction in GA population by

learning human subjective function with a neural network (NN)

By these reduction schemes, we can display only individuals

that mark high fitness. Accordingly, users are expected to evaluate a relatively

smaller number of individuals.

The basic idea of NN learning is from [2,8]. For a

start, we have implemented the “reduction" in GP based on length of

represented rhythm (see section 3.2�).

In a similar way, we tried to learn human subjective fitness function

with a neural network (NN) to realize such reduction in GA population. We

have used a

three-layered network (Fig.

6) for the purpose of learning the human fitness

function. It learns through the back-propagation how a user gives the

fitness value of GA individuals given by a user through the

back-propagationto a GA individual. Inputs to the NN are

elements of array GA genotype and the output is the estimated

fitness value of the phrases

represented by the array. By individual, which the

array represents. By showing the user individuals only get high score with this

NNchoosing

only individuals with a high NN output score, we can reduce the number of

GA individuals that a

user must face

to evaluate.

Fig. 6 The diagram of neural network learninga neural network, which

learns user's criteria.

5. Experimental Results

We have conducted several evaluation experiments

so far. In the first experiment, several subjects with different musical

background and preferences and preferences

used our system to make rhythms whatever they want. Most of the subjects found

our system performance

satisfactory. In another experiment, we gave users the theme for the composition,

such as "rhythms sound like rock’n’roll songs", and then make them

compose music by our system. Fig.

7 shows a typical “rock’n’roll rhythm” generated in this experiment.

A couple of generated rhythms in these

experiments are available from our web site as sound files (URL: http://www.miv.t.u-tokyo.ac.jp/~tokui/research/iec-music/),

some of which will be presented at GA2000.

OnAs for the reduction of GA population by NN,

we got a positive feedback from users. It seems to increase the probability of

breeding a new generation, which reflects the user’s evaluation in the previous

generation. To evaluate the effectiveness of this method, however, we need to

analyse experimental results more quantitatively, which will be our future

work.

Fig. 7 A typical generated rhythm phrase generated by “○○CONGA”.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, we described our research on the

interactive musical composition system. The system enables the interaction

between EC and human beings. We have shown that the system can generate musical

phrases successfully by combining GA and GP.

Our research has two important aspects. One is

to study the basic IEC scheme and another is to develop a novel tool for the

music composition. From the first point view, we should make more quantitative analysis

on the effectiveness of the whole system, especially for the evaluation

assistance by the neural network. For this purpose, we plan to conduct some

psychological experiments with many test subjects. In another respect, we should expand the musicality of generated

phrases. At the beginning, we will embed a mechanism to handle melodies to the

system.

Recent research topics, such as humanized

technology or KANSEI engineering {}, show that now it's timThere is a move to

revise the relationship between computers and human beings in proportion as

computers become indispensable in our everyday life. We believe the IEC

will be one of the most important techniques to embed human subjectivity to the

searching ability of computers. In addition, the progress in the computer

technology will bring us a novel way to make music more enjoyable and exciting.

We hope our research can contribute to this stream.

References.

[1] Anthony R. Burton and Tanya Vladimirova, Application of Genetic

Techniques to Musical Composition, Computer

Music Journal, vol. 23, 1999.

[2] Brad Johanson and Riccardo Poli, GP-Music: An

Interactive Genetic Programming System, In Proceedings

of the Third Annual Conference: Genetic Programming 1998, 1998.

[3] Damon Horowitz, Generating Rhythms with Genetic

Algorithms, In Proceedings of the 12th

National Conference on Artificial Intelligence, AAAI Press, 1994.

[4] David E. Goldberg, Genetic Algorithms in Search, Optimization & Machine Learning,

Addison-Wesley, 1989.

[5] Erick Cantu-Paz, A Summary of Research on Parallel Genetic Algorithms, Technical

Report, Department of General Engineering, University of Illinois, rep.95007,

1999.

[6] Hideyuki Takagi, Interactive Evolutionary

Computation - Cooperation of computational intelligence and human KANSEI, In Proceeding of 5th International Conference

on Soft Computing and Information/Intelligent Systems, 1998.

[7] John A. Biles, GenJam: A Genetic Algorithm for

Generating Jazz Solos, In Proceedings of

the 1994 International Computer Music Conference, ICMC, 1994.

[8] John A. Biles, Peter G. Anderson and Laura W.

Loggi, Neural Network Fitness Functions for a Musical IGA, In the International ICSC Symposium on

Intelligent Industrial Automation and Soft Computing, 1996.

[9] John R. Koza, Genetic

Programming: On the Programming of Computer by Means of Natural Selection,

MIT Press, 1992.

[10] Nao Tokui and Hitoshi Iba, Generation of musical

rhythms with interactive evolutionary computation, In Proceedings of the 14th Annual Conference of JSAI (in Japanese),

2000.

[11] Nao Tokui and Hitoshi Iba, Empirical and

Statistical Analysis of Genetic Programming with Linear Genome, In Proceedings of The 1999 IEEE International

Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, 1999.

[12] Paul Messick, Maximum

MIDI : Music Application in C++, Prentice Hall, 1999.

[13] Unemi Tatsuo, A Design of Multi-Field User

Interface for Simulated Breeding, In Proceedings

of the Third Asian Fuzzy System Symposium, The Korea Fuzzy Logic and

Intelligent Systems Society, 1998.