THE

DESIGN IMPLICATIONS OF TIME-BASED INTERACTIVE MEDIA

School of Arts, Culture and

Environment. The University of Edinburgh

ABSTRACT

Time is central to architectural design, but has not been

fully investigated through computational media. The works of Heidegger [[1]], Bergson[[2]], Virilio[[3]] and Deleuze[[4]] suggest that the study of the elusive concept of time has

more to contribute to an understanding of the human condition than space. One

can argue that contemporary society is being governed increasingly by temporal

structures, as the space of the town square is replaced by time-based

broadcasting and digital communications. We present three digital media

projects that start with the problematic of time, and examine the implications

for architectural design of working with media where time is a primary

consideration. In turn, the projects address “real-time” interaction, “evolution”

over time, and time-space perturbation.

Keywords. evolution; phenomenology of

space and time; time-based architecture

Smooth simultaneity

In

his discussion of new (digital) media, Lev Manovich (1996) notes similarities

in Walter Benjamin [[5]] and Paul Virilio’s[[6]]

approach to “the intervention of technology into human nature.” (Manovich, 1996)[[7]] He points out that

both Benjamin and Virilio equate our perception of the natural with spatial

distance between the observer and the observed. Technology (film for Benjamin

and telecommunications for Virilio) reduces this distance. The fact that

anything can be transmitted anywhere at the “speed of light” makes the notion

of distance redundant. This condition assumes the collapse of the spatial

dimension altogether. Distance and the inevitability of time delay that once

provided the opportunity for assimilation and reflection supposedly cease to

exist. With instant communication comes instant reaction time, a feedback loop

that ultimately can only be handled by computers. Whereas the collapse of

distance is, for Benjamin, marked by the development of film and its ability to

represent different spaces at the same time, Virilio transfers the collapse of

space to telecommunications. The richness of our perceptual field is

diminished, removing what Benjamin calls “aura”. The “collapse” of distance

implies a condition which conflates the observer with the observed, the human

with the machine, the subject with the object, transforming previously discrete

dualities into a blur.

Time-fractured

Perhaps

this fusion and collapse in space and time accounts for one aspect of our

experience with new media. On the other hand our media-saturated experiential

field sometimes presents the character of a fracturing, a kaleidoscopic

confusion of media and images (Tschumi, 1994). The troubling of distance

through film and telecommunications can also be seen as aggravating the gap,

instilling a separator in the observer-observed continuum, fragmenting our

experience, or perhaps giving expression to the already fragmentary nature of

human experience.

Arguably, spatial and temporal

discontinuities are best appropriated when space and time are processed in

relation to each other. For example, film can use time to render spaces disjoint.

Instead of the broad sweeping panorama (smooth), filmmakers cut from one scene to another. Instead

of conveying a scene as one continuous time sequence they introduce an element

of temporal disruption by switching from one spatial location to another. We

note Alexander Sokurov’s “The Russian Ark”, filmed as one continuous 90 minute

take, and spanning several centuries, where the “cut” is achieved at the

threshold, the doorway, the passage, or the gaze that lingers (on a painting),

and from which we awake to a new time frame. Of course cuts can be used to

convey a sense of the smooth. Perhaps in a film and MTV-enculturated world cuts

are everywhere. Whatever the “impression,” be it of smooth or distressed, the

effect takes place at the cut, the conflation, and this is time-abetted. In any

case, it is a temporal plus spatial control that gives new media its power to

explore discontinuity.

Temporal 3D Environments

What

kind of spatial exploration results from digital tools that celebrate and

exploit the time aspect? How does the designer gain access to the unmaking of

smooth space, the fabrication of distressed geometries? How does the designer

play with fractured and disturbed unities? Time-based media provide an

opportunity to play with the smooth and the rough, the continuous and the

fragmented, and thereby explore discontinuities within our experiential field.

Real-time three-dimensional

technologies have only recently become part of the designer’s tool box. Digital

tools that are now commonplace suggest functions and processes that typically

become extensions of traditional design practice. An architect might use 3D

modelling software at various stages during the design process. The ability to

mould and shape surface and volume is provided as an extension to traditional

physical model making. The promise for photo-realistic visualisation comes as a

well-received technological “improvement” on drawings and perspectives. The

smooth ideal draws on metaphors of creation and process that pertain to

temporal-continuity (Lynn, 2003) whereas the distressed exploits intervention,

disruption, event-based discontinuities, the non-linear and the non-local

(Novak, 1996).

THE EVOLUTION OF FORM

The first project

is a generative system for “real-time” 3-D modelling using a procedural

programming language (C++) with access to OpenGL 3D graphics primitives.

Generative models can be used to simulate 3D architectural spaces to successive

levels of detail, thereby contributing to an understanding of design as a process

of evolutionary refinement. The project raises questions of evolution and

continuity through algorithmic events.

![]() This project develops a generative method to

explore time-based 3D modelling for abstract spaces. The algorithm starts with

a simple “key” parameter from which a “self-generative” complex form develops.

The system is based on a “growing tree code” via an L-grammar [[8]].

Almost all elements in the structure are generated to the next stage by

following the “growing tree code” process. The recursive algorithm selects its

branches in this derivational structure according to “the law of possibility.”

Some elements grow faster than others, and some atrophy. The derivation of the

elements is governed by one constant key parameter.

This project develops a generative method to

explore time-based 3D modelling for abstract spaces. The algorithm starts with

a simple “key” parameter from which a “self-generative” complex form develops.

The system is based on a “growing tree code” via an L-grammar [[8]].

Almost all elements in the structure are generated to the next stage by

following the “growing tree code” process. The recursive algorithm selects its

branches in this derivational structure according to “the law of possibility.”

Some elements grow faster than others, and some atrophy. The derivation of the

elements is governed by one constant key parameter.

Figure 1.2

Anti-clockwise radius of gyration

Figure 1.3 Positioned

primary elements and vertical structures by random code

In the

examples shown here, a single element, which we call a “virtual brick,” is to

be located in a certain position and forms the basis of an assembly. This

assembly is then transformed into a complex spatial structure. This is a

flexible, multi-cloning assembly which can be of any scale and extent. Colour,

scale and the position of elements are all determined by the initial selection

of the key parameter. Forms of great diversity can be generated. Figures 2-4 to

6 show the derivation of forms using different key parameter values.

a) test 1 and 2.

b) test 3 and 4

Figure 1.4 Linear form Structure: test 1, 2, 3, 4

Figure 1.5 Example of a

full composition

As we see, a single block of

computer code and variation of a single key parameter results in large

differences in the composition. The compositional possibilities can be explored

repeatedly over a short period of time. The project raises the issue of

evolutionary derivation as a smooth or disjointed algorithmic process. Though

the algorithmic process is smooth, successive runs of the program show

discontinuities. Further discontinuity is introduced by the intervention of

human agency, and multi-user agency in an immersive environment. These are the

subjects of further research.

PERTURBING

THE CONTINUUM

In

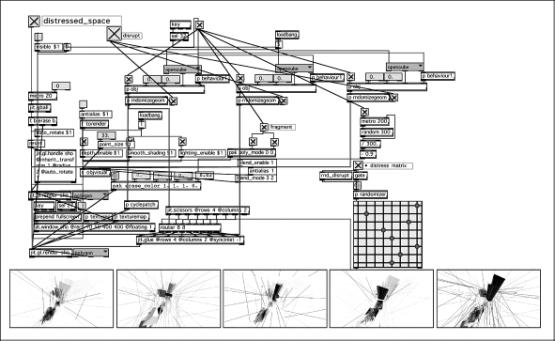

our second project, we developed an event-based system using a set of

programmable objects which are an extension to MAX/MSP [[9]]

graphic programming environment-Jitter [[10]].

Jitter is a collection of 130 or so standard objects which deal with time-based

graphic content. Subsets of these objects are dedicated to video processing,

data manipulation, and 3D Open-GL programming and rendering. The Max/MSP/Jitter

user community is mainly composed of artists, musicians and programmers who

develop applications for audio and video processing, interactive installations

and audio-visual performance.

Max/MSP presents the user with

a graphic interface in which boxes with inputs and outputs are connected

(following the metaphor of circuit design). Each set of boxes (patches) can contain

any number of nested boxes (sub-patches) and communicate with them at various

rates. Its design is primarily for time-based applications and therefore

follows a strategy of rapid prototyping which to some extent by-passes

compilation and de-bugging, hence exposing the error, the accident, the

interference, and makes them available for exploitation. The (application)

design process that is implied in Max/MSP/Jitter tends to be attractive to

non-programmers and to some extent forces a visualisation of decision-making

processes and erratic connectivity. The clusters of boxes and connecting lines

effectively represent a kind of multi-dimensional flow diagram that underlies

the computational process. One of the central aspects of Jitter is the fact

that all data structures are represented as configurable matrixes of specified

data types, dimensions and sizes. A great part of Jitter’s possibilities in the

realm of processing and mapping relies precisely on this fundamental entity.

The values of a pixel array on a screen of 400 by 400 would take the form of a

4 dimensional (RGBA) integer, 400 by 400 matrix. Figure 3 shows an by

connecting/disconnecting, re-configuring in a time-dependent way, and

experimenting while examining the visual or kinaesthetic result.

Figure 2.1 Example of environment with which the designer

interacts

EVENT AND

NARRATIVE SPACE

The time-based medium of Macromedia

Director’s Shockwave 3D [[11]]

exposes a series of 3D primitives, user behaviours, 3D animation strategies and

a real-time physics simulation engine (Havok). Shockwave 3D has been used by

designers of computer games that, due to Shockwave’s standard specifications

and increased computational power of

the average PC, can distribute and play their environments on-line.

We indicate

something of the potential of this time-based environment in our third project

that explores the character of the home as described in Bachelard’s (1964) Poetics of Space,

the home as a

cellar, a garret and a hut. The phenomenon of space

is closely linked to intimacy and memory in Bachelard’s writing. Certain parts

of the house, such as the attic, serve as “repositories” of memories. The house

also provides a person’s protypical spatial experience, a reference point from

which all other spatial experiences derive and with which they are compared.

The house is also understood episodically, in relation to sequences of events

(getting out of bed, bathing, dining, opening windows, etc). From this

perspective, our being-in-the-world is structured narratively. The house serves

as a space for Bachelard’s narrative, and a house is itself a narrative space.

To instantiate Bachelard’s

spatial narrative as a 3D computer model available for game-like navigation and

interaction introduces some startling incongruities. As users of this new space

we sense a familiarity with it, though we are perhaps struck by the mismatch

between the medium and our bodily awareness. Our physical presence is perhaps

reduced and moved into hardware and software. Our sense of recognition is

suspended and the spatial phenomenon reduced to concepts of digital

interaction.

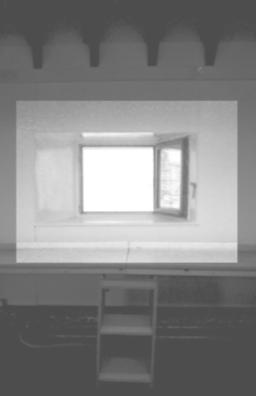

The Shockwave 3D

environment works with concepts of the model, movement, interaction and frames.

It is possible to “jump” from one frame to another, in the manner of movement

from one frame, sequence, or episode in a film. It is also possible to overlay

frames, as in the case of film overlays. We have extended the frame metaphor to a

consideration of a room in the Architecture building [[12]],

data projecting a window as presented in the Shockwave 3D “attic” space onto a

window in the room (Figure 1.1).

The actual window is covered by a screen and an open window is projected (Figure 1.2 & 1.3).

Different interactions are

available, such as opening the virtual window or closing it, or opening a blind

— simple prototypical micro-event that we may have performed many times before,

and that frame our experience and structure our space for the moment.

Of course the familiar event

is rendered strange in this encounter as we see familiar objects projected. As

we encounter something foreign, we draw on the strength of the metaphoric

relations between image and space in order to make sense of our environment. The interaction of the user of this space and the

computer-mediated space draws on the power of metaphorical association. The

project highlights issues of familiarity, interaction, augmentation, the

virtual, narrative and metaphor. We expect that a phenomenological

understanding of such interventions helps develop understandings of digitally

mediated space.

The familiar, homely event of

opening a window is rendered strange, and consequently gives us a new

understanding of the spaces we inhabit. The next challenge is to test this

interaction with subjects to see what narratives of augmentation (metaphors)

emerge. The task will then be to examine multi-user interaction in the same

space, to see how such experiences are negotiated collectively, and through

digitally-mediated communications.

Figure3.1. Picture of house section showing projection.

Figure3.2 & 3.3. Pictures of architecture window projected as closed

window first, and open in the other one.

CONCLUSION

The conclusion of our study is that time considerations can

perturb the impetus towards smooth, seamless interaction and step-wise

derivation, contrary to developments which

seem to aim for techno-human environments that are integrated, seamless and

smooth. It also questions the recurrent digitally-inspired theme of an

architecture based on organic and smooth forms.

The practical application of the

outcomes of these explorations is a means of exploring and generating designs

and patterns, in a way that is algorithmic, interactive and time-based,

utilising computer animation and multi-user control. The challenges include

further developing languages for designing in new ways, and new languages of

interaction design. What are the best ways of interacting with such

capabilities? The interface is unlikely to be smooth and seamless.

One

of the most interesting ways for design practitioners to appropriate these

capabilities is to experiment with tools that are designed primarily for other

than architects and spatial designers. These include computer tools for

animators, artists, choreographers, film makers, and composers. There is also

benefit in collaborating with such practitioners, who bring different

conceptions of space, time and computer capability to bear on the design

process. This paper represents such a collaboration, in our case between

architectural designers and practitioners of the time-based media of musical

composition.

REFERENCES

Bibliography

Bachelard, Gaston.1964. The Poetics of

Space, trans. Etienne Gilson. Boston: Beacon Press. First published in

French in 1958.

Benjamin, W. 1992, Illuminations. Trans. H.

Zohn. London, Fontana Press

Coyne, R.D. (2002). The cult of the not-yet.

In Designing for a Digital World. Ed

Neil Leach. London: Wiley-Academic, 45-48.

Deleuze, G. 1992, Cinema 1 : The

Movement-Image. Trans. H. Tomlinson and B. Habberjam. London, Athlone.

Heidegger, Martin. 1962. Being and Time, trans.

J. Macquarrie and E. Robinson. London:SCM Press. First published as Zein und

Zeit in 1927.

Lynn, G.: 2003, http://www.glform.com/

Manovich, L.: 1996, Film/Telecommunication –

Benjamin/Virilio. http://www.manovich.net/text/Benjamin-Virilio.html (May 2003)

Novak, M.: 1996, Transmitting

Architecture: The Transphysical City http://www.ctheory.net/text_file.asp?pick=76 (May 2003)

Schneider, C.W. &Walde, R.E. (1992), L-system computer

simulations of branching divergence in some dorsiventral members of the tribe

Polysiphonieae (Rhodom elaceae, Rhodophyta).

Eur.J.Psychology.,29:pp165-170.

Tschumi, B.: 1994, Architecture and disjunction. Cambridge, Mass., London, MIT Press

Virilio,

P.: 1991, Lost Dimension. New York,

Semiotext(e)

COSMO3D REFERENCE MANUAL\Program

Files\Silicon Graphics\Optimizer\doc\developer\cosmo3dIndex.html

Karl S CHU; Modal Space. On the

http://synworld.t0.or.at/level2/soft_structures/allgemein/modal_space.htm

End note