Hyposurface: from Autoplastic to Alloplastic Space

Mark Goulthorpe

DECOI Architects, Paris

Introduction

By way of immediate qualification to an essay

which attempts to orient current technical developments in relation to a series

of dECOi projects, I would suggest that the greatest liberation offered by new

technology in architecture is not its formal potential as much as the patterns

of creativity and practice it engenders.

For increasingly in the projects presented here dECOi operates as an

extended network of technical expertise: Mark Burry and his research team at Deakin

University in Australia as architects and parametric/ programmatic

designers; Peter Wood in New Zealand as programmer; Alex Scott in London as

mathematician; Chris Glasow in London as systems engineer; and the engineers

(structural/services) of David Glover’s team at Ove Arup in London. This reflects how we’re working in a new

technical environment - a new form of practice, in a sense - a loose and light

network which deploys highly specialist technical skill to suit a particular

project.

By way of a second disclaimer, I would

suggest that the rapid technological development we're witnessing, which we

struggle to comprehend given the sheer pace of change that overwhelms us, is

somehow of a different order than previous technological revolutions. For the shift from an industrial society to

a society of mass communication, which is the essential transformation taking

place in the present, seems to be a subliminal and almost inexpressive

technological transition - is formless, in a sense - which begs the

question of how it may be expressed in form. If one holds that

architecture is somehow the crystallization of cultural change in concrete

form, one suspects that in the present there is no simple physical equivalent

for the burst of communication technologies that colour contemporary life. But I think that one might effectively raise

a series of questions apropos technology by briefly looking at 3 or 4 of

our current projects, and which suggest a range of possibilities fostered by

new technology.

By way of a third doubt, we might qualify in

advance the apparent optimism of architects for CAD technology by thinking back

to Thomas More and his island ‘Utopia’,

which marks in some way the advent of

Modern rationalism. This was, if

not quite a technological utopia, certainly a metaphysical one, More’s vision typically deductive,

prognostic, causal. But which by the time of Francis Bacon’s New

Atlantis is a technological

utopia availing itself of all the possibilities put at humanity’s disposal by

the known machines of the time. There’s

a sort of implicit sanction within these two accounts which lies in their

nature as reality optimized by rational DESIGN as if the very ethos of design were sponsored by Modern rationalist

thought and its utopian leanings. The

faintly euphoric ‘technological’ discourse of architecture at present - a sort

of Neue Bauhaus - then seems curiously misplaced historically given the

20th century’s general anti-, dis-, or counter-utopian discourse. But even this seems to have finally run its

course, dissolving into the electronic heterotopia of the present with

its diverse opportunities of irony and distortion (as it’s been said) as a

liberating potential.1 This would seem to mark the dissolution of design

ethos into non-causal process(ing), which begs the question of ‘design’ itself:

who 'designs' anymore? Or rather, has

'design' not become uncoupled from its rational, deterministic, tradition?

The utopianism that attatches to technological

discourse in the present seems blind to the counter-finality of technology's

own accomplishments - that transparency has, as it were, by its own more and

more perfect fulfillment, failed by its own success. For what we seem to have inherited is not the warped utopia

depicted in countless visions of a singular and tyrranical technology (such as

that in Orwell's 1984), but a rich and diverse heterotopia which

has opened the possibility of countless channels of local dialect competing

directly with the channels of power.

Undoubtedly such multiplicitous and global connectivity has sent

creative thought in multiple directions…

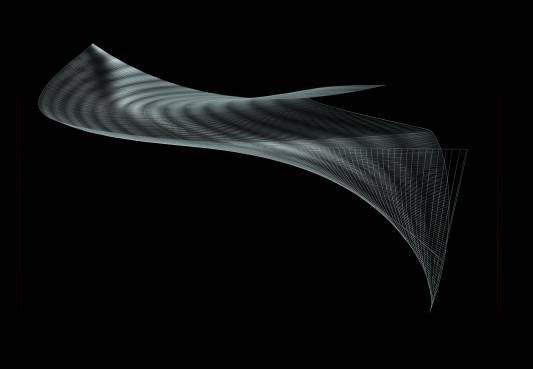

Foster/Design

Such issues of transparency and of

determinism - ‘design’ itself, in a

sense - surface in a formal study we were invited to do for Foster & Partners. This intrigued us initially simply in its

formal potential - its benign complex-curved form. But as we developed various design strategies it began to reveal

myriad other facets of a new creative territory. The project is a giant clam of sorts, an external carapace which

shrouds three internal theatres, the surface swelling differentially over

each. Foster’s had approached it

in classic fashion as an exercise in rational design methodology, but ran

aground in their attempt to generate such a sensual complex-curved form

‘deductively’ – and certainly to understand what they had produced in any

precise sense.

Our approach was not to design the

form - not to define it determinately with a gestural flourish - but to

set constraints by which the form could find itself. Initially we gave an imaginary force to the number of people

within the theatres as a series of diffuse force fields which lifted or

cushioned an elastic surface, and then we produced mathematical descriptions

which gave substance to such elasticity.

In effect we didn't define the

form as a figure in space, but left it as a movement hanging in space – a

reversal of gestural instinct: a sort of Asiatic sense. There’s an elegance to this besides the

flowing form, a curious new aesthetic act: not to design an object, but to

devise the possibility of

an object: it’s not an architecture so much as the possibility of an

architecture. For us it was like

watching determinacy evaporate. But

such model offers what we call a precise indeterminacy, which applies

formally as well as processurally: there’s a rigour and a relaxation - it’s

not an art of the accident!

Formally the object is intriguing - an

elemental fusion and opacity which seems to announce a new formal territory in

which there’s an implicit degradation of property: the roof curls down to become a wall, the structure fuses with the surface, the openings emerge and

merge into the background form by a material tessellation as a languid

intersection of fluid curves in space.

It’s as if all the delineations of Modernist rationality, which followed

on from the tenets of industrial production - the separation of structure,

wall, surface (even of architect, engineer, manufacturer) - dissolve in the

opacity of such formal register. It

cries out for a seamless and reciprocal processing

and for systems of non-standard

post-industrial manufacture

We felt the inexpressivity and occlusion of

this project and the articulate indeterminacy of such creative process

offered a quite compelling reorientation of technical discourse: there’s a

melt-down of technical expressivity, almost, a lowering of its profile to zero,

an almost inexpressive fluidity.

Bremner/Parametric

The Bremner House, at a different scale,

follows on from this where we’re renovating a townhouse in Kensington/Chelsea

in London. Here we're adding a

conservatory to provide a sun-terrace with views up the Thames and in order to

create a unified volume over the awkward corner we’ve simply wrapped it with a

single surface of glass which articulates into flat glass facets. Behind the skin is then a system of

motorized blinds which sheath the space and which will constantly adjust to

create a kind of shrouded cocoon. These

we’ve put on a bus system - a sort of virtual wiring - such that a simple

thermostat and a light-detector are sufficient to create subtle gradations of

movement control.

Strange as it may seem, we’d characterize

this, again, as inexpressive, or indeterminate - a hypo- rather

than hyper- surface, despite it’s distinctive form. The budget was extremely limited so from the

outset we realized that we would need to conform to the parameters dictated by

the contractor - size of glass, minimum angle of panes, etc. So we needed not only a hyper-accurate

description sufficient to allow numeric command machine manufacture but a

system of modelling that was elastic or adaptable such that any change could be

readily incorporated globally. We

therefore developed it as a parametric model, a model where all the

geometries are linked, constrained by various parameters given by the

contractor, engineer, etc. such that any change in those parameters will

globally deform the model. This has

resulted in an extremely competitive bid - of the same order as a rectangular

glasshouse,which we also bid, the contractor reassured that we can offer a

precise description that can readily assimilate his input.

There is certainly an interesting shift in

logic, here, not only in the continuity of creative process into manufacture -

they are seamless, in a sense - but that such elastic descriptive capacity

offers a precision without determinism or without auto-determinism:

the form infinitely more complex than we’d have designed.

It marks the shift, which I’ll qualify more in relation to another

project, from what I’d call autoplastic to alloplastic ‘space’,

both in the creative process and in the architectural itself. Autoplastic

being a determinate, fixed environment - one 'designs', auto-dictates - and alloplastic

an indeterminate, open description, a reciprocal relation between environment

and self.

In our creative process we're here in

a mode of plastic reciprocity: we’re setting parameters which release forms

which we then interrogate technically, aesthetically, etc. Such back and forth

process condenses a compelling final form as a sort of trapping of such

indeterminacy, and which itself, in a quite subtle way, becomes alloplastic

in its responsiveness, in its capacity to modify to environmental stimuli.

Pallas

House (in collaboration with Objectile)

The Pallas

House developed not so much out of a concern for elastic modes of

description, but looked to capture an energetics in material form as a sort of frozen

calculus. The house was for a developer fascinated by new technology

who asked that we try to attain the formal sophistication of product design,

which suggested an approach that utilized generative software linked directly

to automated manufacturing techniques.

The design then developed as an attempt to take to full architectural

scale the experimental generative and manufacturing potential of Objectile

software (Cache/Beauce), which permits surfaces and forms to be generated

mathematically in formats suitable for direct manufacture by CNC machine. But our fascination was much more in the

implied drift of design process into calculus-imagining, and the release of a

new genera(c)tive potential implicit in such working method.

The complex external skin was imagined as a

sort of arabesque screen as a filter to the harsh tropical climate, and it developed as a series of

formulaically-derived complex-curved shells, incised with numerically-generated

glyphs which capture the trace of a curve differentially mapped onto a rotating

solid. At first glance its subtle

morphing is perhaps unremarkable - virtually a standard cladding-surface,

albeit of synchopated rhythm. But at a

level of detail, where the surface captures a movement and develops as a fluid

trapping of thickness, there's a shiver of a new logic, the perforations

opening and closing according to orientation as a sort of frozen

responsiveness: an entirely non-standard surface. As variable electro-glyphs incised in a subtely curving plane,

the project hints at new possibilities of numeric craft and decora(c)tion and a

sort of melt-down of expressivity, a formal diffusion in the capture of

a latent possibility which we characterized as an active inert.

Here the implicit suggestion is that one

might translate the cathode-ray scanning of a screen to a numeric-command

machine (routing, milling, etc) to be able to apply complex calculus

derivatives directly to material surfaces.

The resulting data-derivative, of 'impossible' complexity, was to be

routed accurately in plywood and cast in aluminium or plastic. Here one might say (with Cache) that the image

becomes primary2,

begins to become the operative (pro-active) medium, our design function

displaced to that of fascinated sampler of endless computational

patterning. The skin in this sense

became elastic in that it was no longer conceived as a model or representation

of fixity, but became suspended as a norm-surface,

responsive to parametric input from client, engineer or architect, a flexible

matrix of possibility.

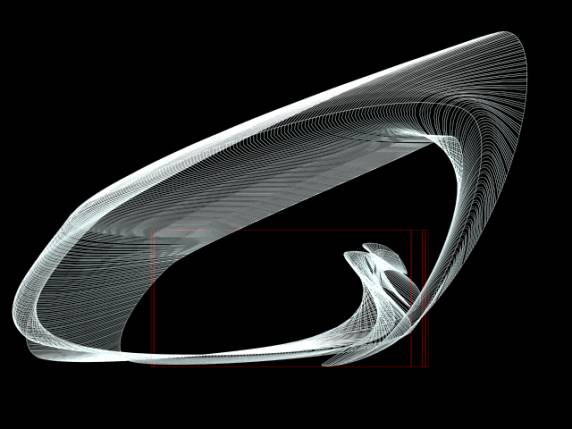

Aegis

The idea of trapping movement was carried

forward in another project, Aegis, which won an invited competition

earlier this year and has now been commissioned. It has developed as a speculation on

the alloplastic condition referred to above, and as a vehicle for

foregrounding current operative design strategies. It was devised in response to a competition for an art piece for

the Hippodrome theatre in Birmingham, specifically for the ‘prow’ which

emerges from the depth of the foyer to cantilever over the street. The brief simply asked for a piece which

would in some way portray on the exterior that which was happening on the

interior - that it be a dynamic and ‘interactive’ art work.

The resultant project is simple

in its conception: one might even say that it is nothing or that it highlights the

nothing – the everyday events which occur in the theatre around it. It is a simple surface - metallic and

facetted - an inert backdrop to events.

But it is a surface of potential which may suddenly be released -

and in response to stimuli captured from the theatre environment it can

dissolve into movement - supple fluidity or complex patterning. It

is therefore a translation surface, a sort of synaesthetic

transfer device, a surface-effect as cross-wiring of the senses. It plays the field of art as it alternates

between foreground and background states, an emergent decora(c)tion

which then vanishes-as-trace.

The surface will be capable of

registering any pattern or sequence which we can generate mathematically, and

launched by an embedded network of half a dozen Scenix microchips. It deforms physically according to stimuli

captured from the environment, which may be selectively deployed as active or

passive sensors. It will be linked to

the base electrical services of the

building which are to be operated using a coordinated bus system, such that all

electrical activity can feed into its operational matrix. But additional input from receptors of

noise, temperature and movement will be sampled by a program control monitor

which will select a number of base mathematical descriptions, each

parametrically variable in terms of speed, amplitude, direction, etc. The elastic surface will then be driven by a

bed of about 3,000 pneumatic pistons, which offer a displacement performance of

some 600mm 2-3 times per second!

As a device of translation

upon translation Aegis highlights the extent of writing systems (mathematical,

programmatic, machine code, etc) in their utter saturation of the cultural

field, writing now become primary.

But the project seeks to emphasize the irreducibly human aspects of such

iterative processes, playing on the slippages between domains and the pleasures

of forms of notation (the ‘elegance’ of programmatic description, for instance,

or the 'humour' of the mathematics).

Certainly we foreground the extent to which mathematics underpins almost

all CAD operating systems, making explicit that which is implicit in

simulations of time and force, revealing their generative precepts. Working with a high-level mathematician has

been liberating (maths is his language

of mischief!), opening rather than delimiting the range of generative

possibility.

Alloplastic

In a sense Aegis explores

potential shifts in cultural as much as technical pattern, looking for new

potentials offered by an electronic creative environment, and for me it begins

to venture into psychological territory – into the ‘psychologies of

(electronic) perception’. The

characteristic cultural strategy of the twentieth century has widely been

characterized as that of shock - a dis/re-orienting wrench of cultural

expectation. Walter Benjamin,in his

essay ‘Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, for instance, characterizes

the effective art-work as a shock, which assaults the viewer, similar to

Heidegger’s term, ‘Stoss’, literally a blow. It was Nietzche who suggested that modern man

“is a reactive, no longer active

creature”, and it is perhaps such cultural reactivity which now begins

to dissipate as we enter a profligate and spontaneous space of digital creativity.

Stoss –

shock – is a reactive strategy, still reliant on a legitimizing cultural

origin and the very structures of representation that it calls into question:

it is a reactivity-against. My sense is of a dissipation of the

shock-effect and the development of irreferent creative processes - metonymic

and freely associative rather than metaphoric and representative. Not so much a dis/re-orientation as an

endless suspension of the possibility of orientation. This has been characterized, quite legitimately,

I think, as no longer a cultural mode of shock but a mode of trauma,

trauma occuring almost as a suspension of shock, a stimulated absence…

Classically trauma occurs as the

struggle of the mind to capture an event which has escaped registration, occurs

on the site of a conceptual gap, the

mind searching restlessly for a missing referent. This motivated suspension, or precise indeterminacy - no

longer reactive but interactive - seems to mark an emergent form of cultural capacity markedly at

odds with accounts of extant cultural patterns. If one looks to Gombrich, for instance, in his ‘Sense of Order’ (circa

1960? and subtitled, interestingly enough, ‘the psychologies of

perception’), he continually asserts that the mind cannot tolerate sustained

dis-orientation and will quickly ground it in reference. But with computational power, as here, to

calculate real-time 10,000 points physically moving in space, where transformation

replaces the notion of origin as operative principle, dis-orientation

and trauma emerge into a fully interactive

cultural milieu. And trauma, as shock, is not simply

debilitating - it stimulates wildly, often triggering neglected modes of

cognition as a highly activated ‘sampling’ of experience, seemingly calling the

bodily senses into play cognitively and creating a highly charged proprioreceptive

state.

The terms autoplastic and alloplastic

to which I referred are psychological

terms, introduced by Ferenczi in his studies of trauma, in which (effectively)

he extended Freud’s notion of trauma as

resulting from dramatic situations of stress, to a much more generalized

social theory. In Ferenczi’s terms an autoplastic environment is one where the

subject is challenged by a highly determining context and is forced to

auto-adapt in the face of such resistance which can lead to neuroses of

trauma. He contrasts this with an alloplastic

environment in which there is the possibility of a reciprocal transformation

in which both subject and environment negotiate interactively.

The terms I implicate here to

make the suggestion that as we seemingly pass to a cultural mode of trauma, we might think this transition in

terms of a shift from autoplastic to alloplastic mode. Both in terms of cultural production

- the fluid processural negotiations with a software environment - and cultural

reception - the transformative effects of an electronic environment becoming

actual.

Paramorph

(Gateway)

A final project, which has just

been shortlisted to the final four in a quite large open competition is a

Gateway to the South Bank in London - simply negotiating between the new Eurostar

terminal at Waterloo and the Royal Festival Hall, National Film

theatre, etc - actually the pedestrian passage under a railway

viaduct. We took a cue from Paul Virilio

in his suggestion that the last vestige of the gateway to the city is the

ephemeral scanning-device at airports, but which for us already extends in

depth throughout the city as a vast network of monitoring and surveillance

devices which regulate, implicitly or explicitly, patterns of behaviour. The gateway, it might fairly be said is

around us and within us, exists everywhere in an electronic urban environment

as an endless sytem of subliminal regulatory thresholds.

The usual refrain is that this

represents the tyrrany of technology, manipulating behaviour

oppressively. But my sense is that

there are many other possibilities as this technological network becomes

multiplicitous - the sort of Jacques Tati vision of technology - where the

endless proliferation ends up in a sort of liberal chaos! Such vision is shared by Gianni Vattimo in

his effective update of McLuhan's technical treatises of the 1960s:

“Contrary to what critical sociology has long

believed, standardization, uniformity, the manipulation of concensus and the errors of totalitarianism are not

the only possible outcome of the advent of generalized communication, the mass

media and reproduction. Alongside these

possibilities – which are objects of political choice – there opens an alternative

possible outcome. The advent of the

media enhances the inconstancy and superficiality of experience… The society of the spectacle spoken of by

the situationists is not simply a society of appearance manipulated by power:

it is also the society in which reality presents itself as softer and more

fluid, and in which experience can again acquire the characteristics of

oscillation, disorientation and play.”

So we imagined the Gateway as Playtime(!)

- a trapping device of the patterns and rhythms of movement of which the

site is a point of confluence - a sort of urban theatre, but a virtual mirror

not of pattern, but of discrepancy: how the site diverges from itself.

‘Trapping’ I use in the double sense of decoration and capture, and as a

means of emphasizing the ornamentality of such technologies in offering

a mapping of patterns of cultural behaviour now no longer as a threshold

condition but dispersed throughout the city, in transit… The site will play

itself back to itself, but geared to its difference from itself, highlighting

the moments at which regular pattern degenerates. It will operate as a play-back device which actually begins to

encourage interraction - a 'ministry of silly walks'!

Again, we’ve worked from nothing,

from the base void presented to us, which we’ve then looked to distort not just

parametrically but paramorphically. A 'paramorph' being a body with the same

constituent elements, but which takes on different forms. Following on from his work mapping Gaudi's Sagrada

Familia church in Barcelona, Mark

Burry developed a paramorphic principle beginning with a constrained cube, but

which warps off plane by plane as a sequential transformation of the same.

The initial form was derived from the idea of trapping noise - that the

noise of the overlapping transport systems will cause the paramorphe to distort

radically, here into convoluted loops.

But the apparently non-standard and serial deformation of the resultant

series of shells belies a common principle or property, which in this case

is that they are describeable with ruled surfaces, lend themselves to ready

description and hence construction…

We are still thinking through the

consequences of this latest technological strategy, but undoubtedly we’re beginning to explore a quite new creative

possibility: that of a constrained yet radically open environment...

Conclusion

In these projects we

continually find ourselves asking 'what ‘is’ technology?' We take it in a broad cultural sense, as

have many of the thinkers of technology this century: for Heidegger, technology

as Ge-Stell, enframing, man continually setting up frames by which to

comprehend and modify being. Even McLuhan, who was quite specific about various

technologies, defines technology quite vaguely and non-technically as the

‘extensions of man’ - not simply a mechanical

prosthesis but any

sense in which man ‘outers’ his internal capacity. For him, too, technology is not merely an external device, but

one that actively infiltrates back within the organism, changing patterns of

thought and cultural desire: “man creates a tool, the tool changes man” -

changes his imagination, crucially.

So we might think of technology as the base

cultural textile,as the pattern of thought itself, almost. But this would be to take, certainly

Heidegger, to a quite radical conclusion - that technology is not just the sum

total of the machines at man’s disposal, but encompases the shifts in the

patterns of thought they engender. But

in light of the current technological shift, which is not so much informatic

machines and their calculating power, but more crucially a global society

coming to terms with electronics (with greatly expanded possibilities of mass

communication) it seems justified to stretch Heidegger a little. In fact that’s the question, I think: to ask

to what extent current shifts in the very nature of technology demand an

interrogation of accounts such as Heidegger’s or Benjamin’s.

Such questions might preface how we, as

architects, capture the liberties and pleasures offered by such transition -

the shifts in cultural and not merely technical possibility. And

if one doubts the possibility of cultural liberation engendered by technology

one only has to think of Benjamin’s ‘Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’

which announces the loss of ‘aura’ of the art-work without pessimism (with

enthusiasm, actually), the cult value of the art-work and its basis in ritual

giving way to its exhibition value, to art’s being able to participate

much more closely in quotidian life…

In looking for the potential of a new

technology, for new patterns of cultural production and reception, I think that

there is a new environment of reciprocity opening which one can begin to

identify and act upon, which perhaps begins to ‘make legible’ the full range of

parameters that impinge on the act of architecture. Suddenly the entire process can

factor in the design methodology: we’re able to ‘relax’ a form of Foster’s to

reflect fluctuations in budget, able to capture the patterns of habitation

real-time in form, able to map patterns of discrepancy.

This, then, is simply an attempt to

understand how we’re working - not conjecturing too much about how we will

work, but simply qualifying the experience of practice that’s happening to us

in the present. Our response to the

question of rapid technological change is positive, but reflective, as we seek

to recognize the current technological shift underway and to interrogate it not

just in its evident formal capacity but in its quite subliminal affect on

cultural manner. Heidegger and Benjamin take on crucial

significance in this, and their evident inheritors - McLuhan, Derrida, Vattimo

- and I find my desire to disturb or stretch their formulations (as, I admit, a

still-reactive cultural practitioner) qualified by an appreciation for

their insight. Most particularly for

Benjamin’s optimism which I think has been born out in the liberalism of

the present.

In talking of technology Heidegger suggests

that the setting up of Ge-Stell, of

frameworks, enables man to separate a World from the Earth.

That he says ‘a’ world and not ‘the’ world I think is poignant,

suggesting that there are myriad possibilities available in what has evidently

become a technological heterotopia. It’s the differences and dialects of that

new environment that seem to me compelling, and which we as a team variously

pursue, looking to explore the range of cultural possibility offered by a new

technology - its liberating pleasures - in multiple ways…

CREDITS

FOSTER/FORM - formal Studies for Foster & Partners

Design Team: Mark Goulthorpe, Gaspard Giroud, Arnaud Descombes

Technical Design: Prof Mark Burry at the University of Deakin, Australia

Mathematical Studies: Alex Scott, UCL

LUSCHWITZ/BREMNER HOUSE

Kensington, London, 1999

Design Team: Mark Goulthorpe, Gabrielle Evangelisti

Technical Design: Prof Mark Burry of the University of Deakin, with Greg More

Engineers: Tom Grey of RFR, Paris

PALLAS HOUSE

Bukit Tunku, Malaysia, 1997

Design Team: Mark Goulthorpe,

Matthieu le Savre, Karine Chartier, Nadir Tazdait, Arnaud Descombes, with Objectile

(Bernard Cache, Patrick Beaucé)

Engineers: Ove Arup – David Glover, Sean Billings, Andy Sedgewick

HYSTERA PROTERA

Studies in the decora(c)ting of structure, 1996

Design Team: Mark Goulthorpe, Arnaud Descombes

AEGIS

Design Team: Mark Goulthorpe, Mark Burry, Oliver Dering, Arnaud Descombes

Technical Support: The University of Deakin, Australia: Prof Mark Burry, Grant Dunlop

Programming: Peter Wood, University of Wellington, NZ

System Engineering/Design: Chris Glasow of Andromeda Telematics, London

Mathematics: Dr Alex Scott, UCL

Engineering: David Glover and Sean Billings of Ove Arup & Partners, London

PARAMORPH

Competition for a Gateway to the South Bank, London, 1999

Design Team: Mark Goulthorpe, Gaspard Giroud, Gabrielle Evangelisti, Felix Robbins

Design/Technical support: Prof Mark Burry, the University of Deakin, Australia, with Grant Dunlop, Greg More

Electronics/Audio: Chris Glasow, Louis Dandrel

Engineers: David Glover, Sean Billings, Ove Arup & Partners, London